It's Time for California to Get Out of the Oil Business

California is a leader in reducing demand for fossil fuels—supply, not so much

A scene from West Texas? No, it's an oilfield near Bakersfield. California is a leader on climate action but also one of the country's top oil-producing states. | Photo by Mark Ralston/AFP/Getty Images

IN THE LATE 1920s, the Methodist Community Church of Santa Fe Springs, California, was going broke. The town's pious, churchgoing farmers had leased their land to oil companies and fled to the coast to escape the industrial blight, and the roughnecks who replaced them weren't exactly the tithing kind. The church elders initially resisted collaborating with the wildcatters but soon gave in. With the understanding that any royalties would redound to the church, they allowed the General Petroleum Company to raise a derrick and spud a well on church property. Black crude gushed forth, just as the oilmen had predicted.

Oil resolved the church's debts, paid for repairs, and even financed a fleet of buses to bring the self-exiled congregants back home for Sunday services. Twelve years later, the church had become so enamored of oil that its pastor, Reverend Harry G. Banks Sr., proposed "erecting a living memorial to the genius of oil workers in Southern California."

Most of the oil wells in Santa Fe Springs have since played out. But the industry that saved Banks's church persists, leaving its oily carbon footprint on California. Los Angeles would not exist in its current form were it not for its long history of oil extraction; in Beverly Hills, a boundary-defining thoroughfare bears the name of oil tycoon Edward L. Doheny. Bakersfield, a busy hub in Central California's Kern County, was a farming backwater before the discovery of its major oilfields at the tail end of the 19th century. The famed Getty Center, its travertine walls sparkling above the 405 freeway, exists because of the riches that oil baron J. Paul Getty passed on to his trust when he died. Some of those riches were made in Santa Fe Springs.

In 1938, the same year that Banks proposed his monument to oil, a British steam engineer named Guy Callendar theorized that the carbon dioxide emissions of the industrial age were raising the temperature of the planet. Callendar thought that might be a good thing, in that it might avert the next ice age. By the time he died in 1964, most scientists were already pretty sure that we were heading for trouble. According to the latest assessment by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, humans have at maximum 20 years to lower emissions of greenhouse gases or face irreversible climate disruption of an existential order.

Signal Hill, near Long Beach, California, 2003. Oil contributes $111 billion a year to the state's economy. | Photo by Spencer Lowell

IN SEPTEMBER 2018, I stood inside the fence at the Global Climate Action Summit at San Francisco's Moscone Center, listening to protesters call for an end to oil drilling in California: "I hear the voice of my great-granddaughter saying, 'Keep it in the ground.'" An eight-foot chain-link barrier separated them from the conference-goers, and security personnel and police paced defensively, keen to block access to anyone without preapproved credentials. Pleading my case to a tall man in a black suit, I considered the irony of all this muscle employed to protect attendees at a climate summit from a crowd composed largely of silver-haired women with bright scarves around their necks.

When I finally negotiated my way in, I ran into former state senator Fran Pavley, author of many of California's landmark climate laws. While Pavley wholeheartedly supports a phaseout of California oil production over time, the protests struck her as "sometimes counterproductive." She wondered, as did many other climate wonks, why activists were picking on California, which has done so much to address the climate threat. After all, Texas produces seven times as much crude, and North Dakota has laid waste to its western flank by fracking for shale oil. Many of their lawmakers don't even acknowledge that human-caused climate change exists.

In focusing on California, author and 350.org founder Bill McKibben told me, the climate activists' strategy was based on the "hope they might succeed." The action at the Moscone Center on the opening day of the climate summit culminated a year of activism by environmental justice advocates aimed at then-governor Jerry Brown. Organizing under the label #BrownsLastChance, the activists wanted Brown, in his final months in office, to stop permitting new oil wells and announce a systematic phaseout of oil production combined with investment in job training and reemployment opportunities—a "just transition"—for oil workers. The previous weekend, some 30,000 people had occupied San Francisco from the Embarcadero to the Civic Center, one of more than 800 events in 91 countries that day associated with the global Rise for Climate, Jobs, and Justice movement.

Earlier, the coalition had written letters and sponsored a series of billboards: "Dear Governor Brown," one read, "Is dirty oil the future you will leave our children?" In April 2018, the coalition even launched a "thermal airship"—a blimp-shaped hot-air balloon—over the Bay Area emblazoned with a message: "Climate Leaders Don't Drill." In July, 26 climate scientists sent a letter to the governor: "California is both one of the nation's top oil-producing states and one of the world's largest and most prosperous economies," they wrote. "California has both the ability and the moral imperative to address fossil fuel extraction."

Brown's press secretary responded by quoting the four-term governor as saying that "no jurisdiction in the western hemisphere is doing more on climate." He wasn't wrong. Under Brown's watch, the state set a 100 percent renewable energy goal by 2045 for electric utilities, gave car companies specific quotas for zero-emission vehicles to market in the state, and established a model carbon-trading market.

A pumpjack in L.A.'s Wilmington neighborhood. Across California, more than 5 million people live near an oil or gas well, two-thirds of whom are people of color. | Photo by Nacho Corbella

But those remedies only address the demand side of the climate problem: the consumption of fossil fuels. On the supply side—actual fossil fuel extraction—California regulation has been weak to nonexistent. In 2011, early in his third term, Brown notoriously fired Derek Chernow, director of the Department of Conservation, and his deputy, Elena Miller, who oversaw the Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR). Chernow and Miller had begun holding drillers to state and federal laws written to protect drinking water and worker safety, hence slowing down permits. In 2013, Brown backed industry amendments on a fracking transparency bill—authored by Pavley—including one that allowed drillers to frack for two years with virtually no oversight while the state commissioned a study. Brown proved such a reliable ally to the Western States Petroleum Association, the industry's well-funded lobbying arm, that its president, Catherine Reheis-Boyd, wrote an editorial in the Sacramento Bee celebrating his leadership.

Now the state has a new governor, Gavin Newsom, who refused campaign donations from the oil industry. He said in a preelection debate that "the fracking experiment is beginning to wane" and declared in a letter to the Trump administration that California is no longer "interested in the boom-or-bust oil economy." That pleases Monica Embrey, senior representative for the Sierra Club's Beyond Dirty Fuels campaign: "There's a great opportunity for Governor Newsom to lead on how California can transition off oil." That opportunity includes, she notes, "how to support parts of our state that are currently economically tied to the extraction industry."

An immediate halt isn't going to happen. But a gradual step-down, combined with a tax on oil production that could fund a just transition for workers, would send a message to other oil-producing governments with green ideals, such as Norway and Canada: If you're sincere about holding global temperature rise below 1.5°C, you can't just reduce the consumption of fossil fuels. You have to cut production too.

"There's more carbon in already-producing fields globally to blow way past one and a half degrees," says Kassie Siegel, the director of the Climate Law Institute at the Center for Biological Diversity. "There's no way that any new fossil fuel development can be compatible with a safe climate." Rejecting new permit applications, Siegel says, is entirely within the state's power. At present, however, according to the Department of Conservation's senior staff counsel James Pierce, the agency almost never overrides local land-use authorities' judgment to do so. If the state did what Chernow tried to do and transferred oversight from field offices to Sacramento, DOGGR could turn down future permits on the grounds that they violate the state's fundamental environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act.

That would come as a shock to the more than 200 oil companies that operate in the state, pump $111 billion into its economy each year (which is 2.7 percent of its gross domestic product), and are a major force in Sacramento. In the 2017–18 legislative session, the Western States Petroleum Association sank $13 million into influencing elected officials; Chevron alone spent $12.8 million.

Oil showed what its money can do in the November 2018 election. In a state senate race in Southern California, business-aligned Democrat Susan Rubio bested her more progressive opponent, popular former state assembly member Mike Eng. Eng was endorsed by labor unions, police, firefighters, the California Democratic Party, and many environmental groups, including the Sierra Club. Rubio had $2.8 million in independent expenditures from oil companies.

Lobbying money doesn't guarantee success, however. Democrats now hold a two-thirds majority in the state legislature, and there are far fewer oil-friendly members than in past years, when the so-called Mod Dems could hold up legislation the oil industry didn't like. Meanwhile, public opinion has begun to shift. Fourteen years ago, only 39 percent of Californians considered global warming a "very serious threat," according to surveys by the Public Policy Institute of California; now, 56 percent do. The same majority of people expect gas prices to rise if the state sets policies to reduce global warming but support such action anyway.

"Often the response is that [phasing out oil] is not politically realistic," Siegel says. "We need to make it politically realistic."

SIXTY YEARS AFTER the Santa Fe Springs church struck a mother lode of oil, Harry Banks's grandson, Jeff Smith, is showing me around the Kern River Oil Field in Kern County, at the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley near Bakersfield. Along with us is Sue McLain, the project analyst for Smith's company, Maranatha Petroleum. A famous bluff overlooks the oilfield below Panorama Drive—a street name that conveys Bakersfield's distinct pride in this view. Back in 1845, when Edward Kern, the topographer on John C. Frémont's third expedition through the American West, nearly drowned in the river that now bears his name, this valley was a tangle of cottonwoods, willows, and sycamores, raucous with birdsong and frogs. Now there's only the steady hum of pumpjacks and distant traffic.

McLain and Smith, whose adult lives have been invested in the oil industry, see the vista as a testament to progress and the nodding pumpjacks as symbols of a recovering industry. If the air on certain days is bad for the lungs, McLain insists, it's not because of toxic emissions but because of the Fresno Eddy, a circular wind pattern that pushes marine air south into the San Joaquin Valley and back north again when it hits the Tehachapi Mountains. In 2017, the San Joaquin Valley Air Basin exceeded national standards for ground-level ozone on 85 days of the year and the state standard for large particulate matter—smoke, soot, and dust—on 145 days.

Smith is 72, tall and white-haired, with decades of experience in the oil industry. He spent most of those years working for the "majors"—corporations like ExxonMobil and Chevron—before striking out alone to start his own company. "I wanted to see how good I was," he says. "Also, I just wanted to wear shorts to work." He admits he's part of a dying breed—the independent oil developer. "Pretty soon, the environmental regulations are going to make it too expensive for the little guy," he says. "Only the big companies will survive."

Before encountering Smith, I'd emailed dozens of petroleum geologists and engineers. Most never wrote back. Of the two who did, one combed through my Twitter feed, concluded we had nothing in common except a love of baseball, and sent me to a website run by a conservative think tank to learn how carbon dioxide is actually good for the planet. Smith, however, responded enthusiastically and didn't ask for a debate on global warming. He offered candor as long as I didn't ruin his local reputation. "It's extremely important to me, being born in this town, having gone to high school right across the street, and having our school mascot be a driller, that I'm not misquoted," he said.

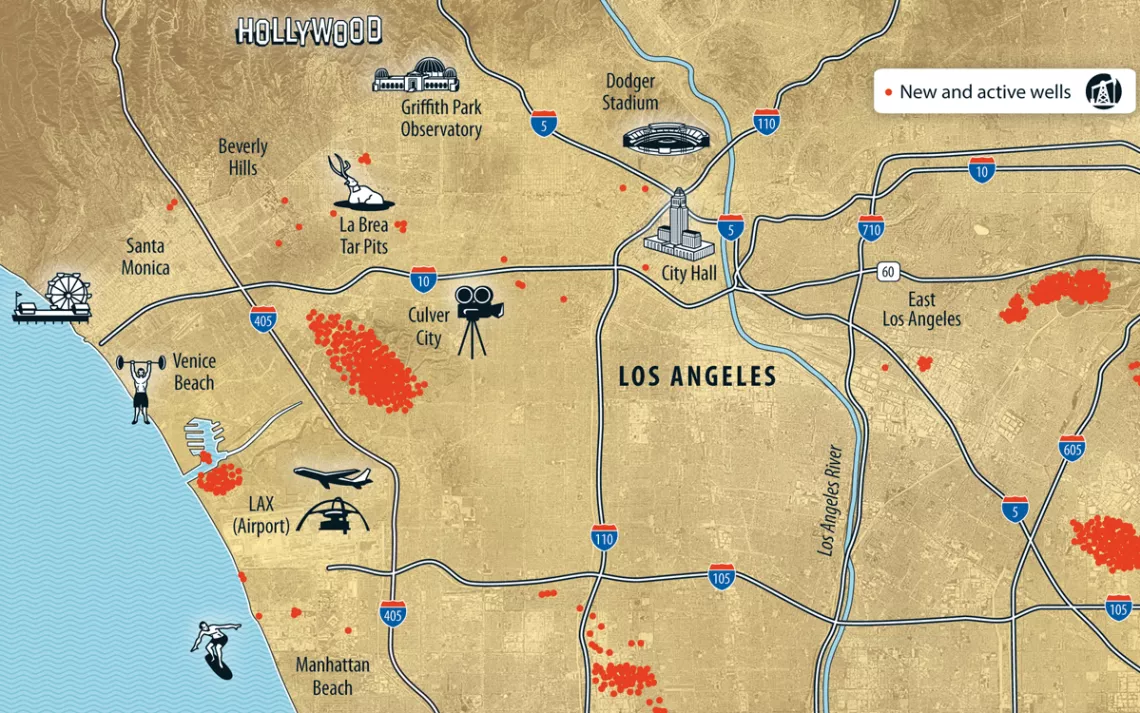

Los Angeles is an oilfield with 4 million people living on top of it. Look carefully behind the cul-de-sacs and golf courses and you'll see bobbing pumpjacks (indicated in red on the map). The environmental justice group Stand-L.A. counts 1,071 active wells in the city, 759 of which are within 1,500 feet of homes, schools, churches, or hospitals. | Map by Peter and Maria Hoey

Kern is California's most oil-rich county, producing nearly three-quarters of the crude that makes California one of the top five oil-producing states. Its economy depends on agriculture nearly as much as on oil, but oil jobs pay better—an average of $94,000 a year versus $36,000 for full-time agricultural work (which is almost never full-time year-round). Oil's philanthropic footprint is everywhere in Bakersfield: The burn clinic at the local hospital is funded by Aera Energy, one of the region's largest producers, and in 2018, Chevron donated $2 million to the state university's School of Natural Sciences, Math, and Engineering.

Smith himself pursues only primary recovery. His wells, dotted throughout the Fruitvale Oil Field near Bakersfield, extract available oil closest to the surface using standard technology. He doesn't drill in the Kern River Oil Field, where the primary oil has long since been exploited and recovering what's left requires more complicated "well-stimulation techniques." There is some hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, which involves injecting a slurry of sand and chemical fluids into barrier rocks, and some well acidizing, where chemicals such as hydrofluoric acid are used to dissolve the rock. But more common in the San Joaquin Valley is steam injection, a process in which superheated steam is pumped into wells, melting viscous oil like peanut butter in a saucepan so it can be drawn up by a pumpjack.

Steam injection has allowed drillers to recover more oil than was ever thought possible, but the natural gas burned in the process, plus the heavy quality of California oil, makes it particularly dirty. Three years ago, Deborah Gordon, then director of the energy and climate program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, ranked different types of oil by their carbon emissions at all stages, from extraction to refining to burning. Gordon calculated the kilograms of CO2 (or equivalent) emitted by a given barrel of different types of crude. Ultralight Kazakhstan Tengiz came in at 463, while Canadian Athabasca, from Alberta's oil sands, emitted 736. Oil from California's largest and oldest field, Midway-Sunset, came in just behind, at 725 kilograms of CO2 per barrel.

Most California oil stays in California, but the state still imports 57 percent of the oil it consumes, primarily from Saudi Arabia, Colombia, and Ecuador. Petroleum coke, the sludge-like byproduct of refining oil, is too dirty to burn under California's air laws, so it's shipped overseas by Koch Industries out of the Port of Long Beach.

Smith and McLain are both Kern County natives. Smith grew up in Bakersfield; his father was a car and truck salesman, his mother a teacher. McLain literally grew up in an oil patch. Her father worked in the pipeline department of the Richfield Oil Company, which was active in the San Joaquin Valley until 1966, when it merged with the Atlantic Refining Company to become ARCO. Both have experienced oil's boom-and-bust firsthand and more than once. When oil prices started crashing in 2014, going from $106 a barrel in June 2014 to $27 a barrel in January 2016, many pumpjacks went silent in the Kern River Oil Field, and 1,200 oil-industry workers in the county lost their jobs. Smith had meant to retire in 2014. Instead, he found himself struggling to pay his bills, rolling over debt from one month to the next. "Imagine," McLain says, "suddenly one month getting only a quarter of your usual paycheck."

In November 2018, with the price per barrel topping $80, Maranatha Petroleum finally had enough in the bank to develop new wells. When I visit Smith and McLain's office, they have a work table piled with papers related to their upcoming permit applications. The county does the bulk of the permitting, per a blanket environmental review that state regulators and Kern County's board of supervisors approved in 2015. That review was hotly contested by the county, whose lawyers argued that the rules were much too strict, and by environmental groups—including the Sierra Club, which filed suit against it. "The ordinance keeps the public from having input over the next 20 years," said Gordon Nipp, vice chair of the Club's Kern-Kaweah Chapter, in a press conference at the time. "We think the public should know when there's a new well being drilled."

"They lost that battle," Smith contends, "because it's for the greater good"—by which he means beneficial to the region's oil-dependent economy. The Kern Economic Development Corporation estimates that 23,000 people in the county are directly employed by the oil and gas industry, the vast majority exclusively in oil. Chevron is the county's fourth-largest private employer, right behind C&J Energy Services, a well construction and completion firm based in Houston. Both companies, however, have recently slashed their workforces. C&J emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings in 2017, cutting its staff from 10,000 to 6,000. Chevron has laid off more than 300 employees within the past year. More jobs will be lost, obviously, if new well drilling stops.

Severin Borenstein, a well-known energy economist at the University of California, Berkeley, warns against arguing about the jobs that will be lost in the shutdown of any industry. Derrick and drill operators, roustabouts, and roughnecks, he says, all have useful sets of skills that can apply to a variety of jobs: "We're in an economy with very strong employment prospects. It's not like those people would be forever unemployed." Outside of a recession, industries don't create jobs; they just move them around. "We need to recognize," he says, "that our economy is inherently dynamic."

The Sierra Club's Monica Embrey notes that many jobs would be created during the long process of retiring California's oilfields. "Plugging all those wells is going to be a lot of work," she says. "And people with knowledge and skills will need to do that work." Some of the decommissioning could be paid for with a "severance" tax on current oil production, something that every oil-producing state except California has.

Borenstein, however, is skeptical that a full phaseout of California oil is worth it. The 367,000 barrels of oil produced daily in Kern County account for revenues of $38 million a day, or $14 billion a year, money that gets spread out among grocery stores, hospitals, restaurants, hotels, and schools and would likely just go away as the industry died. The Kern Economic Development Corporation estimates that 40,000 residents of the county earn their living "thanks to direct or induced impacts" of the oil and gas industry.

"The cost per ton of greenhouse gas emissions would be enormous," Borenstein says. "If we're going to get the world to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we're going to have to do it in a way that doesn't impose a cost on consumers."

"People have been invoking economic crises to avoid dealing with the climate for decades," says Peter Erickson, a Seattle-based researcher with the Stockholm Environment Institute who studies the economic-versus-climate impacts of California oil. By automating its drilling operations, "the oil industry has been working hard to employ fewer people as it is," he says. Erickson estimates that oil production would decline by about 10 percent per year were DOGGR to begin rejecting new permits. Right now, without any systematic planning at all, revenues are already decreasing by 7 to 8 percent. The difference is that one scenario is predictable and stable and the other is not.

AFTER OUR OILFIELD TOUR, Smith and McLain escort me to lunch at Noriega's, a Basque restaurant where everybody sits at one long table and passes around tureens of cabbage soup and plates of corned beef and Cornish game hen. Everyone talks and introduces themselves; it's like one big oil-industry family. On the street around the corner, however, there's a different side to Bakersfield: a man swaddled in ragged blankets, his body curled tight to sleep on a precarious bus bench; a woman standing in an intersection holding a sign asking for food or money. Twenty-two percent of Kern County's residents live in poverty; Kern ranks among the five poorest counties in the state. The January 2018 count of homeless people there found a 38 percent increase over the year before.

Some people in Kern County blame communities farther south for relocating unsheltered people in Kern, an accusation without evidence. Poverty is a known side effect of any economy tied to a volatile commodity, be it Central American coffee, Canadian gold, or oil. Sociologists call the phenomenon the "resource curse," says Erickson's colleague Georgia Piggot, a sociologist herself: "Communities that have a higher level of dependence on natural resources have a higher level of social disorders." Paradoxically, she says, phasing out oil production could result in more long-term stability in Kern County, and in California in general.

Piggot compares the proposed phaseout of California oil to the ban on new offshore oil exploration that New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern announced last year. "No one is saying, 'We're going to turn off the taps overnight,'" Piggot says. "What they're saying is, 'This is what the future looks like.'" They're signaling that the fossil fuel era is drawing to a close.

Were California to send a similar signal by not issuing permits for new wells, oil-rich jurisdictions of the state would need to start planning for the industry's eventual exit. That would include, Piggot says, "not training people for jobs that aren't going to exist in the future."

That clean energy future is already underway. Kern County—and the San Joaquin Valley in general—is a sunny, windy place with thousands of acres of disturbed and degraded land, ideal for large-scale solar and wind projects. According to a study by the UC Berkeley Labor Center, 22 percent of new jobs associated with California's renewable energy mandate have thus far gone to the San Joaquin Valley, many of them in Kern County. AFL-CIO president Richard Trumka, speaking at the Global Climate Action Summit on its opening day, singled out the San Joaquin Valley, where "4,000 megawatts' worth of clean energy projects" have been built in the past two decades, with 15 million job-hours of union work. "That's what it looks like," he said, "when we partner to fight against climate change and for good jobs."

Public health concerns are also working in favor of clean energy. Last summer, the Kern County city of Arvin prohibited new oil and gas sites near residential areas. The city and county of Los Angeles, after studying the health effects of living near oil operations, are considering similar ordinances. In Culver City in western L.A. County, public health advocates, led in part by the Sierra Club's Clean Break Committee, persuaded the city council to initiate a study on how to phase out oil production in the city. The move was a turnaround for the council, which less than a year previous had planned to expand extraction of crude from the Inglewood Oil Field, part of which lies under the city.

A decision by California to discontinue oil production could be exponentially beneficial to the climate fight in the near term. The climate activism led by teens and young adults, the momentum behind various Green New Deal proposals, the ongoing effort to gather public support for moving off fossil fuels—all would be galvanized by California moving beyond its long history of dirty oil. In the same way that California's early greenhouse gas reduction policies influenced lawmakers and the public in other states, a California policy to phase out oil could influence the world.

"It could give needed momentum to what is legitimately an uphill battle," Erickson says. "If any state can do it, California can."

This article appeared in the March/April 2019 edition with the headline "The End of California's Oil Patch?"

This article was funded in part by the Sierra Club's Our Wild America campaign's Beyond Dirty Fuels Initiative.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club