Eight Mile Is Alabama's Chemical Katrina

Residents of this community have lived with a noxious smell for over six years

Raquel Williams with her sick son, Markell | Photo by Meggan Haller

FOR YEARS, THE COMMUNITY of Eight Mile, Alabama, has lived with the rotten-egg stench of tertiary butyl mercaptan, the sulfur compound added to natural gas to give it a detectable odor. In 2008, up to three tons of mercaptan leaked from a gas storage facility behind Gethsemane North Cemetery, where local utility Mobile Gas taps into a pipeline to supply its 89,000 area customers. The compound gradually seeped into the groundwater, causing a stinky mess. The people who live around the cemetery say the odor is more than a nuisance; it's a health hazard, and they are both sick of it and sick from it.

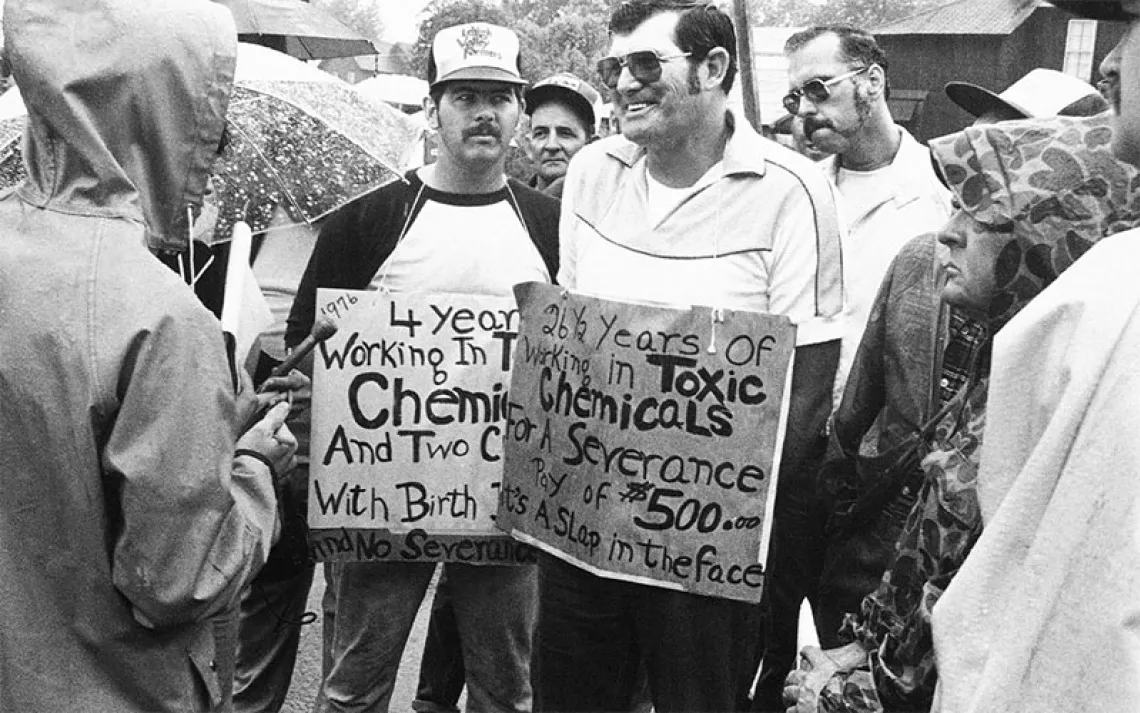

Carletta Davis is the president of We Matter Eight Mile, the community organization that formed to tackle the problem. She calls the situation a "chemical Katrina"—a disaster overlooked by authorities because it mostly affects low-income African Americans. "This is unprecedented, we understand," Davis said. "But we are constantly reporting that this chemical is harmful, and we're having adverse health effects because of the exposure."

Davis has an eight-year-old son who has suffered from asthma, nosebleeds, and headaches since the smell began. "It's all, 'We don't regulate that. We don't oversee that. It's not our division,'" she said.

According to court records in the numerous lawsuits filed against the company, Mobile Gas dug up and hauled away 40 cubic yards of dirt in response to the 2008 spill. But in 2011, the smell of mercaptan started hanging over nearby streets, and neighbors called Mobile Gas to report a leak. The company found and fixed one, but the smell persisted. People complained about dizziness, headaches, nausea, and nosebleeds. Their children were wheezing and coughing. Resident Toni Craig Bumpers said she had migraines, while her daughter, Jania, had difficulty breathing and broke out in rashes.

"They did all kinds of testing to see if she had allergies. There was nothing, so they just said she had asthma," said Bumpers. But since the family moved to Mobile, "she hasn't had to be on her asthma pump in two years."

The human nose can pick up the smell of mercaptan at concentrations of one part per billion. The compound irritates the skin, eyes, and mucous membranes; in high concentrations, it can damage the lungs. But while mercaptan's short-term effects are well documented, there is no literature on long-term exposure.

By the end of 2011, state regulators had tracked the stench to a beaver pond 500 yards from the pipeline junction. A water sample taken from the pond in February 2012 revealed mercaptan at a ratio of more than 14,000 parts per billion. Air samples taken in April by the EPA ranged as high as 230 parts per billion. Workplace safety rules limit exposure to 500 parts per billion for limited periods of time.

In mid-2012, researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Alabama Department of Public Health, and the Mobile County Health Department canvassed the neighborhood and found that more than a third of the people they talked to had sought care for problems like eye irritation, breathing difficulty, and congestion.

Mobile Gas has set up a treatment system that sucks up groundwater, uses ozone to break down the mercaptan, and releases the treated water into a nearby tributary. A dirt road at the back of the cemetery is now lined with monitoring and recovery wells. The system has treated more than 48 million gallons of groundwater to date.

But it could take decades to remove all the mercaptan, said environmental chemist Wilma Subra, who is advising We Matter Eight Mile. Subra said the cleanup needs to focus on removing the contaminated soil and groundwater that remains. "It's still migrating from the source area to the point where the recovery wells are, and it's migrating from the source area to the spring," she said.

Company records cited in the lawsuits suggest Mobile Gas may have lost more than 6,000 pounds of mercaptan in the first half of 2008—"several times the amount ordinarily used in an entire year," one document notes.

Mobile Gas disputes the size of the spill; at the time it claimed that only about 1,200 pounds of mercaptan were lost. Jenny Gobble, a spokesperson for the utility's new corporate parent, Spire Energy, said she is confident Mobile Gas "appropriately handled the situation in Eight Mile." The amount lost "has always been safe," Gobble told Sierra via email, and Mobile Gas is trying to clean up the mercaptan "as quickly as possible."

Mercaptan breaks down in sunlight, so the smell subsides during the day, only to come creeping back at night. Bumpers's mother, Julia Lucy, lives less than a mile from the cemetery. She said that the stink has eased since the treatment system was put in, but sometimes it's as bad as ever. "Nobody sees a sense of urgency to come out here and do something about it," Lucy said.

The Alabama Department of Public Health has done little to ease community concerns. "These odors can impact the quality of life—because of the fact that they are there, people feel sad and get upset. We understand this," a 2016 statement from the department said. But all information about mercaptan "indicates that it is nontoxic at permissible levels."

Such responses leave people like Bumpers feeling depressed—and a bit gaslit.

"You're sick, and you're going through so many things, and people are telling you there's nothing wrong with you when there really is something going on," she said. "And they make it like you're crazy. The doctor's like, 'There's nothing wrong,' and there is."

The neighbors' complaints have gotten renewed attention in recent months. The county health department has begun a new study of the symptoms people are reporting. In October, members of We Matter Eight Mile traveled to Montgomery to demonstrate outside the state capitol and meet with Alabama governor Robert Bentley. Davis said Bentley aides have met with several people in the community since then, but she doesn't see a whole lot of movement. She can still smell the substance nightly from her house, about half a mile from the cemetery.

"In my opinion, the permissible level is zero," Davis said. "There should not be any unnatural chemical in our neighborhood, period."

This article appeared in the May/June 2017 edition with the headline "Alabama's Chemical Katrina."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club