Following John Muir's Trail in Scotland

A writer navigates John Muir Way through the Sierra Club founder's motherland

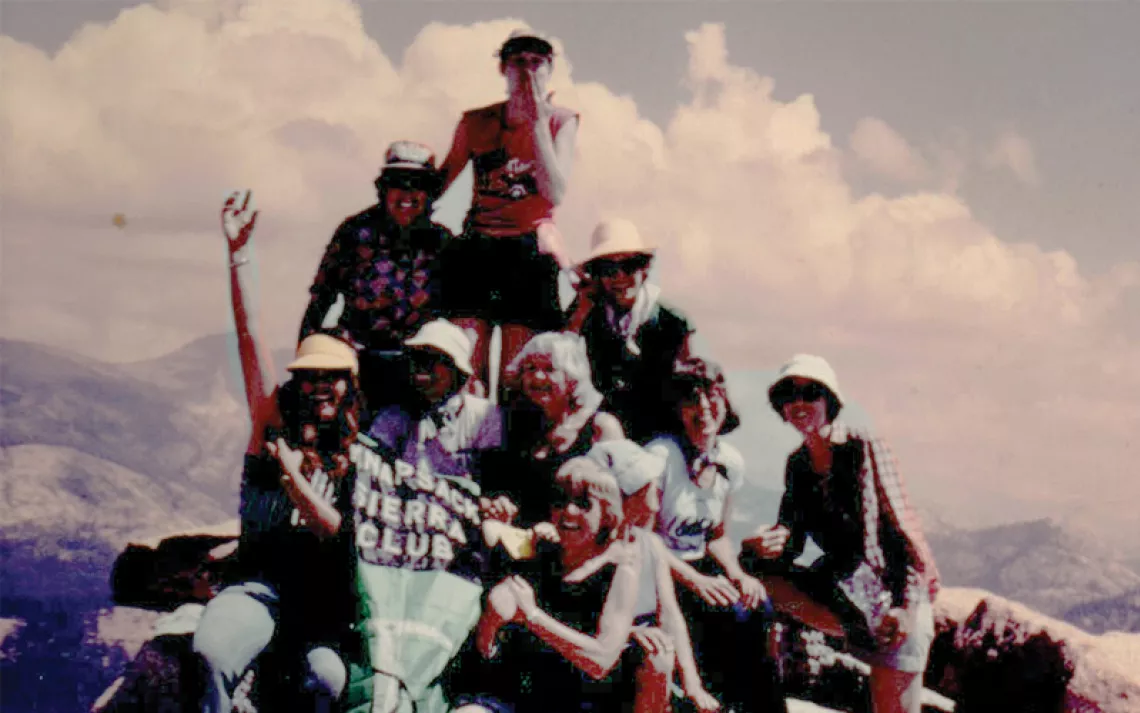

John Muir Way was completed in 2014 for the 100th anniversary of Muir's death. | Photo by Jeremy Miller

IT WAS MID-MARCH, AND RACEHORSES tore across the television screen at a pub in Dunbar, a town on the windswept coast of eastern Scotland. My dad's arthritic knee was aching, so we took a seat at the bar, awaiting a bus that would carry us back to the small village where, hours earlier, we'd begun a leisurely 7.5-mile hike.

"What brings you in?" the bartender asked as he pulled two pints of Guinness.

We explained that we'd just visited the birthplace of John Muir, a stone's throw from where we sat.

"John who?"

"Muir," I replied. "Born right across the street."

"Never heard of him."

"The environmentalist. The man who saved Yosemite National Park."

He nodded apathetically, then returned his attention to the horses of Cheltenham.

Though the Sierra Club founder isn't as recognized in his home country as he is in the United States, Scottish officials are trying to change that. In 2014, a 134-mile, cross-country trail through the quaint villages and hilly lowlands of southern Scotland was designated as the John Muir Way. My father and I had negotiated the segment stretching from the village of East Linton to a couple of barstools in Dunbar.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

The landscapes along the John Muir Way are a far cry from those of the glacially carved Sierra Nevada. Muir's motherland of East Lothian is mostly hedgerows and rolling green hills. Even the official guidebook acquiesces to the domestic and un-Muir-like nature of the scenery: "He probably wouldn't have been interested in this Scottish route and might have been baffled by its use of his name," it reads. And yet, such diminished expectations are overstated, I think.

Though Muir left Scotland in 1849, at age 10, his homeland left a deep impression on him. On his "thousand-mile walk" from Kentucky to the Gulf of Mexico, Muir carried a book of verse by Scottish poet Robert Burns. Muir returned only once to Scotland, in 1893, when he was 55. Of course, the naturalist made time for strenuous walks in the East Lothian countryside, scouring the land for evidence of bygone geological epochs: "I find fine glacial studies everywhere," he wrote.

Muir also visited ruins of ancient castles and abbeys, places of childhood memory. But among the manmade sights, it was the farmland that stirred him most. "This was a fine specimen of the gentleman farmers' places and people in this, the best part of Scotland," Muir recounted in a letter to his wife. "How fine the grounds are, and the buildings and the people!"

As Dad and I had walked along Muir's same path, flocks of starlings had swarmed overhead as tractors churned the earth beside the slow-flowing River Tyne. In the rocky soil of one field, we found fragments of delft-style dinnerware. As we pressed on, farmland gave way to the great, gray arc of Belhaven Bay. We crossed the sand, skirting a golf course (this is Scotland, after all), and climbed to a tall headland. Below the fairways and greens, a scene of geological chaos—a smattering of craggy islands and gray tidepools—unfolded. A little farther on, we found the bloodred sandstone cliff where young Muir discovered his love of climbing—atop of which the crumbling ramparts of Dunbar Castle stand. I could almost see him as a young man, clinging to the sea-scraped precipice, honing the skills that would serve him decades later in the ragged granite of the Sierra. (For one of Muir's harrowing climbing escapades, see How Not to Climb a Mountain.)

Illustration by Steve Stankiewicz

Two hours later, we arrived at Muir's birthplace, an unassuming, three-story row house on Dunbar's main drag. Inside, docent Pauline Smeed noted our American accents and hazarded a guess at our place of origin.

"California?"

She clearly knew our type—Gore-Tex-clad pilgrims chasing the ghost of the great conservationist. The museum that stands today, she explained, opened in 2003—a testament to Muir's mounting importance.

"We didn't want to make it the sort of museum that focused on what kind of curtains they had," Smeed said. "We wanted a place that talked about Muir's environmental vision." Indeed, the museum traces Muir's early life and the evolution of his philosophy. Throughout, swatches of his writings, along with images of Yosemite's Half Dome and El Capitan, hang on the walls.

We stayed until close, savoring the relics of the conservation movement's beginnings. When we finally left, I half expected to emerge into the Yosemite Valley that Muir famously helped preserve—to behold the majestic vistas where his legacy thrives. Instead, we entered a quiet village bathed in the blue light of a Scottish evening. Here, among Muir's gentler, more subdued haunts, his spirit is, still, unmistakably present.

---

Where: John Muir Way, traversing the Scottish countryside between Helensburgh in the west and Dunbar in the east.

Getting There: A car is helpful for reaching more remote segments, but the trail skirts Scotland's two largest cities, Edinburgh and Glasgow—easily reachable via public transportation.

When to Visit: May through July. Long, sunny northern days grant hikers more time to enjoy the landscape. However, the trail is passable year-round.

Must-See: The dramatic tidal flats of Belhaven Bay and the mountain vistas of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park. The mechanically minded Muir would have loved the Falkirk Wheel, a rotating lift that hoists barges from the Forth and Clyde Canal to the Union Canal.

Pro Tip: Since the trail stitches together a tangle of roads, trails, and easements, spring for the official John Muir Way Guide from Rucksack Readers (bit.ly/jmwguide), which offers topographical trail maps, historical tidbits, and bus and train timetables.

Additional Reading: John Muir: His Life and Letters and Other Writings (Mountaineers Books, 1996), edited by Terry Gifford.

More: johnmuirway.org

This article appeared in the May/June 2017 edition with the headline "A Scotsman's Homecoming."

Take a Sierra Club Outings trip to Scotland. For details, see sierraclub.org/adventure-travel.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club