Concrete Farmland

In the shadow of Vancouver’s BC Place stadium, vibrant red tomatoes, strawberries, and lush leafy greens shoot up from their beds atop a former parking lot. This plot, named False Creek Farm, spans two acres across the urban landscape. It's the largest of four farms run by Sole Food Street Farms, an agriculture-based nonprofit, in the city’s Downtown Eastside.

Sole Food Street Farms is rooted heavily in agriculture, generating 50,000 pounds of produce annually from its different locations, but its central mission is to empower its employees and the local neighborhood, economically and socially. The organization works toward a multiproblem solution, providing fresh and locally grown produce to the city—using otherwise empty space—and providing work for underserved residents.

“We’re trying to use the same instincts, the same goals that would exist on a larger, open, rural farm and apply that to a smaller, more intensive space,” says Michael Ableman, executive director and cofounder of Sole Food.

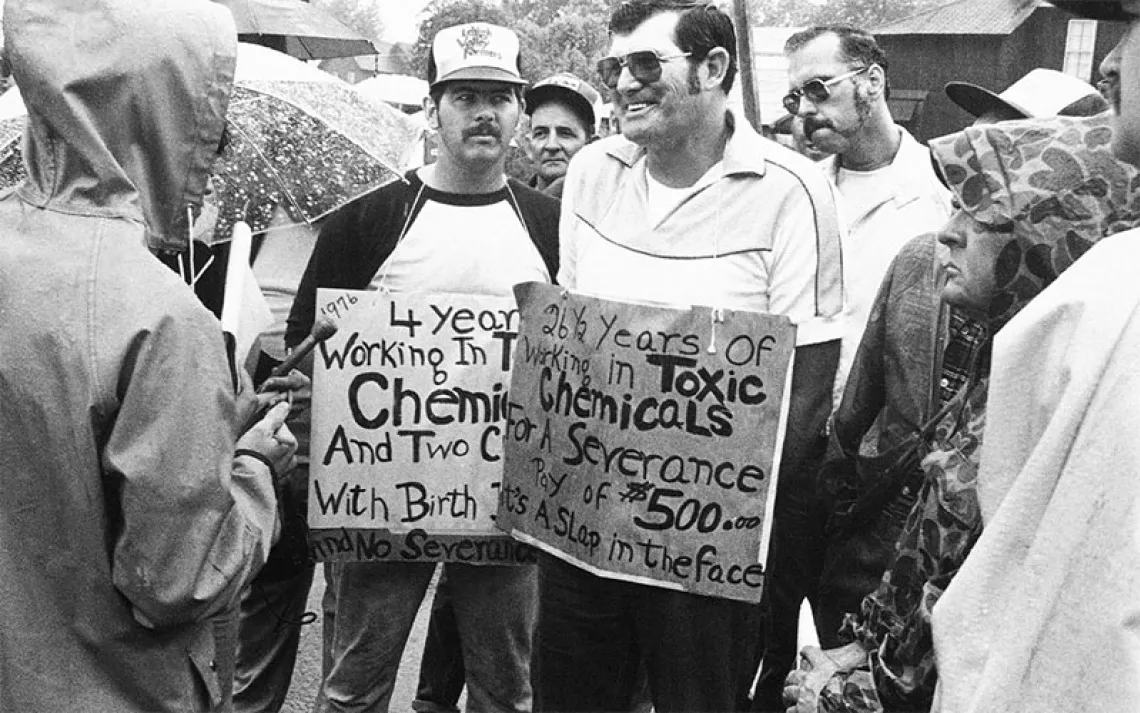

When Sole Food started in 2009, cofounders Seann Dory and Ableman first thought of the social good urban farms would provide for Downtown Eastside, deemed Canada’s poorest neighborhood. To date, Sole Food Street Farms has employed almost 100 people. Most of the current 25 workers are local residents, many of whom have struggled with addiction issues or mental health problems. Ableman told Sierra that the farms provide employees with steady and meaningful work, an income, and an education about farming and agriculture.

“This was not a bleeding-heart attempt to save anyone,” Ableman says. Rather, urban agriculture can work long-term to help resolve social issues and give back to the community. In addition to creating jobs, Sole Food has innovated technology to maximize its output of crops, mainly through raised, portable wooden boxes that allow for high-density planting. The volume of produce allows the farms to sell to 30 restaurants, participate in farmers' markets city-wide, and donate some crops to the local community.

Now is the time for environmental journalism.

Sign up for your Sierra magazine subscription.

Urban agriculture also has its environmental advantages. More than half the world’s population now live in cities, and moving farms and agricultural production closer to these hubs would cut down on the resources used to transport produce. “Food miles” refers to the distance food must travel to reach consumers, in other words, the environmental impact of bringing fresh fruits and vegetables from farm to table. Growing food in the city lessens the distance food travels, encourages people to eat in-season, and brings them more in touch with the production of the crops.

But despite its benefits to Vancouver, Sole Food faces serious challenges. As the city grows and land becomes more lucrative, the nonprofit faces a space shortage. Namely, the city is looking to put in temporary low-income housing in Downtown Eastside, a project that will force one of Sole Food's sites off its current plot.

Instead of completely losing the land, Ableman says there is a possibility for community integration between the orchard and new housing developments. Continuing to develop Sole Food's approach to how urban agriculture can work will help it respond to cities', landowners', and communities’ changing needs.

Ableman knows there are limits to Sole Food's system. Not every crop is suited to grow in the type of planter the farms use, and cities’ growing populations might limit the expansion of urban agriculture. But he’s also seen the benefit that urban farming has brought to his employees. He rejects romantic perspectives on urban farming that claim it might be possible to “feed the city within the city” but instead advocates for an integrated system where farms in and out of cities meet the growing demand for food. On the urban farms, he says, the work has been life-changing and life-saving for some of the people he has worked with.

For Sole Food Street Farms, urban agriculture is a part of the solution to social issues through an environmentally friendly project. “My goal is to focus on the social benefits,” Ableman says. “But also on the agriculture.”

Photos are from the upcoming book Street Farm: Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope on the Urban Frontier (August 2016) by Michael Ableman.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club