The inner workings of the avian mind

In "The Genius of Birds," Jennifer Ackerman explores new research that shows how closely bird brains resemble our own

Neurobiologists once thought that birds possessed tiny, reptilian brains hardwired for instinctive responses to the world. Now they know better. In her latest book, The Genius of Birds (Penguin Press, 2016), Jennifer Ackerman explores new research that shows how closely bird brains resemble our own. They, too, have a cerebral-cortex-like system in the forebrain, rapidly firing neurotransmitters, and pathways between the brain regions.

And like humans, birds demonstrate complex intelligence and a capacity for technical and social skills. New Caledonian crows use their beaks to trim grooves into the leaves of the pandanus tree, making a kind of saw used to "wheedle" insects out of tight spaces. This instrument demonstrates craftsmanship, problem-solving, and even culture—favorite tool designs are passed from generation to generation.

Birds also show signs of empathy: When one raven attacks another, spectators will console the victim, "preening it, bill twining, or touching its body gently with the beak while uttering soft, low 'comfort' sounds."

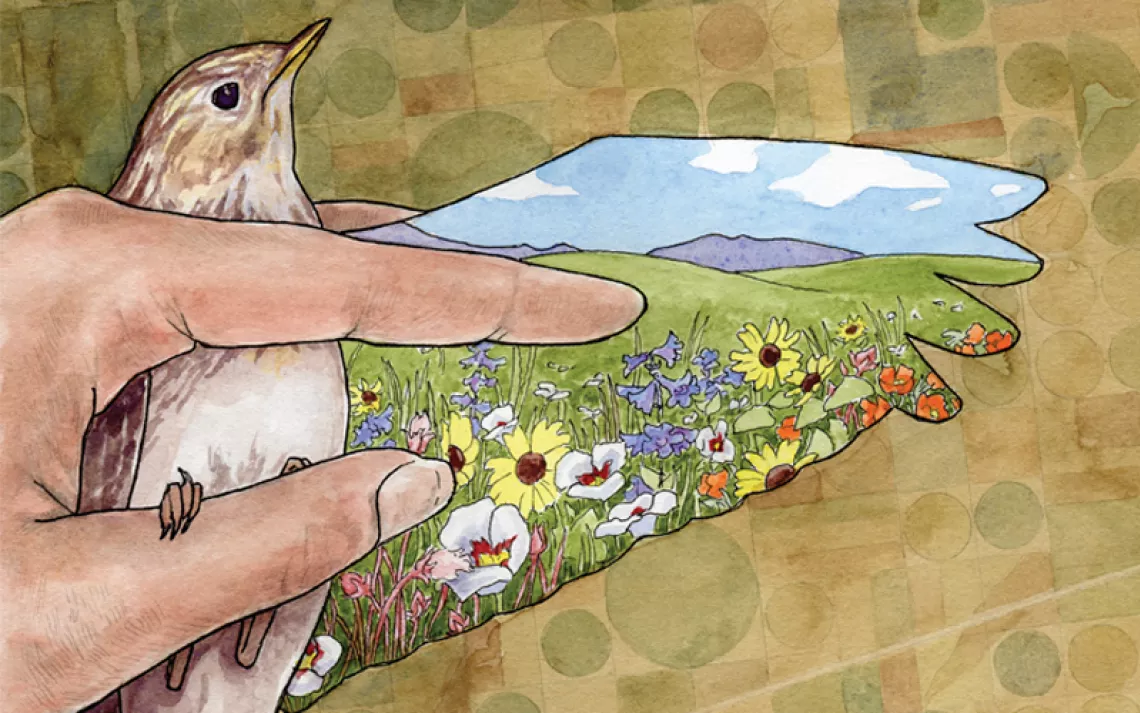

Not all birds are smart—for example, the flightless and near-extinct kagu that ran toward the author in New Caledonia. According to Ackerman, we don't yet know why some birds develop bigger brains. It might be because they've had to use their quick, adaptable wits to overcome a paucity of food or mates. What seems like stupidity in a bird, she writes, might actually be long-term adaptation to easy living. This leads her to wonder whether, as the planet warms and natural habitats dwindle, "we humans, in creating novel and unstable environments, are changing the very nature of the bird family tree."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club