Tiger Liquidators

Lumber Liquidators was turning virgin trees from the world’s last Amur tiger habitat into floorboards, until a team of undercover environmentalists penetrated its shady supply chain.

Correction: The original version of this story misidentified the Chinese company from which Lumber Liquidators was purchasing illegally sourced wood. That company should have been referred to as Dalian Xingjia Wood Products Company Limited. Sierra regrets the error.

IT WAS FREEZING COLD WHEN Alexander von Bismarck woke up in his car, in the middle of a forest at the eastern edge of Russia. Fresh snow coated the ground. He couldn’t see the tigers in the forest around him, but he knew they were out there, flashes of orange in the spaces between trees. This was one of the last places on Earth where Amur (or Siberian) tigers roamed free. He was here, in some sense, to keep their home intact.

Tall and pink-cheeked, von Bismarck is the director of the Environmental Investigation Agency, an international nonprofit that often uses spylike tactics to expose illegal, environmentally harmful networks trading in wood and wildlife. Though generally calm, even subdued, he harbors a fiery affection for the world’s forests. He’s spent much of the last two decades sniffing out illegal loggers in Russia, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

Holding a video camera, von Bismarck and two other men stepped out of the vehicle. One of his companions, an organized-crime detective from Vladivostok, was armed with a handgun. All of them wore camouflage clothes. They found grooves in the snow—the path of a bulldozer—and followed them, their ears alert for the grind of chainsaws.

The trio caught loggers that day in 2008, and von Bismarck captured a video of a man cutting into a protected tree with a chainsaw—but he also glimpsed something even more elusive than the people who were decimating the region’s forests. Beside the grooves of the bulldozer were circular depressions. “There’s a few feet of deep, cold, crunching snow, and you come across a fresh, absolutely giant paw print,” he said. It was a reminder that the thinning forests of the Russian Far East remain singular, magical, and worth fighting for.

WORLDWIDE, UP TO 30 PERCENT of harvested timber is cut illegally. According to the World Bank, this criminal industry generates $10 billion to $15 billion in illicit, untaxed revenue each year for unscrupulous loggers.

Over the last two decades, the Russian Far East has become a hot spot for such criminal logging. The region’s remoteness makes its supply of virgin hardwoods a treasure trove. Some of its trees are 400 years old, but they’re disappearing fast. Between 2001 and 2013, the Russian Far East lost an area of woodlands the size of Kentucky, mostly to fires and illegal logging. A 10-year study by the World Wildlife Fund estimated that each year the region was exporting up to four times the amount of wood that was legally allowed to be harvested. Understaffed and sometimes corrupt forest governance is largely to blame. Investigations by several environmental groups have revealed that the area’s approach to forest management is heavily influenced by “timber mafias,” logging companies that bribe their way into protected forests and cut whatever hardwoods are in highest demand by retailers of wood products—often oak, elm, pine, and ash. Most of the world’s last 400 Amur tigers depend on these forests, as do indigenous people, who use them for beekeeping, hunting, and nut collection. As the largest trees are depleted, loggers push into more remote regions that once seemed beyond their reach.

The most infamous purchaser of this wood, of late, has been the U.S. discount flooring giant Lumber Liquidators, much of whose oak flooring originates in these forests and ends up in American homes, according to research by the Environmental Investigation Agency. The Lumber Liquidators case broke open for von Bismarck in 2011—three years after his snowy encounter with the logging brigade—when he led a team posing as wood buyers to the Chinese town of Suifenhe, where they made contact with a lumber concern called Dalian Xingjia Wood Products Company Limited.

After analyzing customs records and visiting multiple logging sites just over the Russian border, the team had learned that Xingjia was importing large amounts of illegally cut Mongolian oak from Russia and selling it to Lumber Liquidators. On multiple visits to the company’s partner factories, they had photographed boxes with Lumber Liquidators logos. Now they wanted to know how apparent it would be to the Lumber Liquidators buyers that the supply chain was corrupt. If Lumber Liquidators was importing illegal wood, then it was violating the U.S. Lacey Act, which prohibits the known import of illegally logged foreign lumber. Violators of the Lacey Act face fines or jail time.

Suifenhe is a frontier town, a gold rush settlement for wooden ore. You can stand on a bridge above the train yard, said von Bismarck, and look down on “a sea of lumber 20 tracks wide, 80 percent of which is illegal.” On either side of the tracks, mills and factories climb the slopes surrounding the town. Companies like Xingjia mix the Russian lumber with wood from Europe and the United States and then send it to these factories for refinement into floorboards, door frames, and other shelf-ready products to be sold in the United States, China, and Japan.

Hidden behind a wall of disguises—fake names, business cards, phone numbers, and a website—the team arranged a meeting with Xingjia within a day of their arrival in Suifenhe. A company vehicle picked them up and drove them around town, showing off the company’s private rail spur, where it received wood from Russia. At a restaurant, they were introduced to high officials from the local military, the customs department, and the courts, whom Xingjia had on hand to flaunt its immunity from Chinese law enforcement.

The diners sipped on Chinese liquor while discussing their blooming partnership. Von Bismarck, struggling to preserve his cover while keeping pace with his hosts’ drinking, was asked to give a speech. Throughout the meal, the Xingjia representative described his illegal sourcing practices with little provocation. “Their relationship had been going on with Lumber Liquidators for at least five years and was their single most important relationship, according to what they told us,” said von Bismarck. The jovial mood was periodically interrupted when the traders described their years-long fatigue: Dealing with Russia’s timber mafias was a grueling and often unpredictable process, involving bags of money, secret meetings, and, sometimes, violence. “There were some telling moments when someone would almost be wistful and say, ‘This isn’t going to last very long,’” said von Bismarck. At one point, after taking a piece of fish, he was able to stick a GoPro camera on the lazy Susan in the middle of the table, spin it, and capture his fellow diners on video.

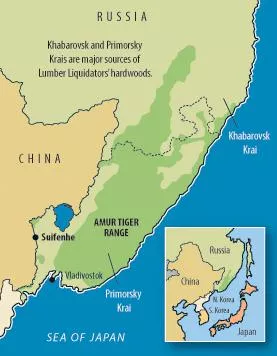

Khabarovsk and Primorsky Krais, in Russia, are major sources of Lumber Liquidators' hardwoods. | Illustration by Peter and Maria Hoey

THE ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY released a report in 2013 based on its research into Lumber Liquidators and the Russian-Chinese lumber pipeline. It estimated that Lumber Liquidators had received 70 football fields’ worth of oak flooring from Xingjia between May of 2012 and August of 2013, half of which, according to a Xingjia executive, came from Russia. Von Bismarck’s group fed its findings to U.S. government investigators. A month later, federal agents raided Lumber Liquidators’ warehouse in Toano, Virginia.

Since then, Lumber Liquidators and some of its suppliers have spiraled downward. The CEO of a Russian timber company that sold to Xingjia was convicted of organized crime and sentenced to 15 years in a penal colony. In February, Lumber Liquidators announced that it expected to be charged for violating the Lacey Act. This was followed by a 60 Minutes segment that outed Lumber Liquidators for selling flooring that contained formaldehyde at levels far exceeding the legal limit. In May, Lumber Liquidators suspended the sale of all Chinese-made laminate flooring, and its CEO, Robert Lynch, unexpectedly resigned. Between late February and June, the company’s stock prices dropped by nearly 70 percent. Despite all this, the company has never admitted that its oak flooring was sourced illegally from Russia. Lumber Liquidators refused to comment when asked if wood from Xingjia could still be found on store shelves.

“Their response to the criticism has been lip service,” said Jesse Prentice-Dunn of the Sierra Club’s Responsible Trade Program, which works to stop the import of illegal woods into the United States. Strong charges against Lumber Liquidators, he hopes, will pressure other companies to keep their supply chains legal and sustainable, and deter them from turning the world’s most precious habitats into flooring for America’s living rooms.

This article has been corrected.

This article was funded by the Sierra Club’s Responsible Trade Program, which receives grants from the Environmental Investigation Agency.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Write to the Department of the Interior and Department of Agriculture and tell them to fully and vigorously enforce the Lacey Act. When buying wood products, ask salespeople about the legality and sustainability of their store’s supply chain.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club