That Wide-Eyed Look

Six ways to inspire awe in children with math and nature.

Math can seem magical through the eyes of a child. Click through the slideshow to uncover the Fibonacci sequence as it appears in nature.

Hidden inside an apple there is a secret. Pinecones are magic, and there is something to learn from an artichoke.

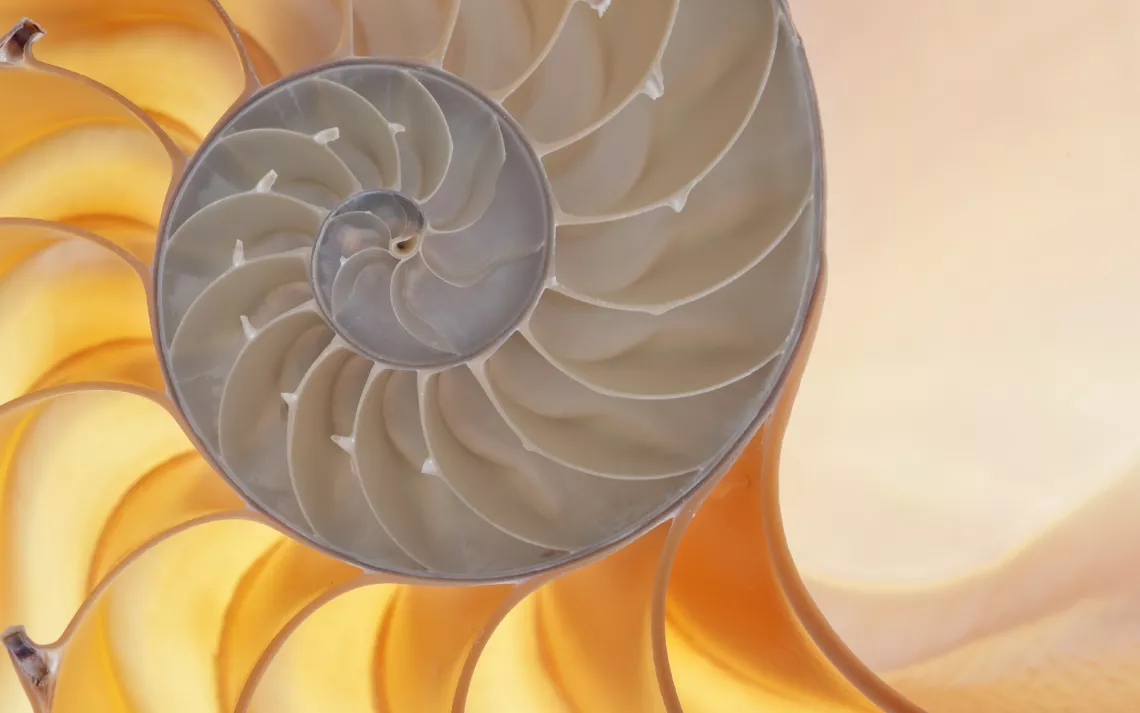

Most adults are familiar with the Fibonacci sequence—a series of accumulating numbers where the next number is found by adding the previous two together beginning with zero and one. The chain of numbers produced (0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144…) describe natural phenomenon from leaf growth to the curl of a shell. Even the human body displays Fibonacci proportions.

If you want to get into the nitty-gritty, grab some graph paper and draw out the Fibonacci spiral. This video is a good five-minute refresher.

Each box’s height and width is a Fibonacci number, and when a curving line is drawn through each box, the expanding spiral is easily seen. The curl increases at a rate of 1.168, also known as phi or the golden ratio. It comes down to math, but to children, nature is miraculous if you look close enough.

But how do you get children to look at all when cartoons are more captivating than flowers and pinecones? David Sobel of Antioch University would say the answer is simple: Play. Sobel is a professor and scholar of play. For more than 40 years he has developed place-based environmental education programs that focus on fun—creating houses for “forest fairies” out of leaves and twigs, building forts and making maps. Play influences sustainable behavior later in life, so children should be free to roam, dig, hide, run and construct outdoors. With a little facilitation, these activities can get kids to bond with brooks and birds more than any traditional lesson.

Tell your children to hunt for the curling Fibonacci shape outdoors and they will start to see the patterns everywhere, in the cowlick on their brother’s head and in spider webs—places where there aren’t really Fibonacci patterns. But the beauty is that they are noticing. Instead of staring at a video game screen on long road trips, they are looking at clouds. Walks may take longer as they stop to look at every little thing, but how can anyone complain?

It’s not about being right; it’s about making observations and encouraging children to forge their own connections with nature. Sobel understands the math, but admitted he never quite grasped the whole Fibonacci thing. “Whenever I look at a sunflower, I always have trouble seeing it,” Sobel says. Even if the mathematics are too advanced, it is never too early to start pointing out patterns. Kids need direction to focus their attention—after that, the discoveries they make are entirely their own experience.

“We have to get toward experiential learning,” Sobel says. He recalls romping and tromping outside, playing a tracking game with his friends as a young child. This game sticks out in his memory as when he first made a connection with nature. “Transcendent experiences in nature drive you to the inclination to protect nature,” Sobel said. Exposing the implicate patterns in nature is just one way of bringing society back down to Earth—one scavenger hunt at a time.

Follow Sierra on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, and YouTube.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club