The Man Who Survived a Polar Bear Attack

In 2013, Matt Dyer was nearly killed by a polar bear on a Sierra Club Outing. One year later, he returned to the wild with the people who saved his life.

On a rocky subalpine trail in the Sierra Nevada, amid the rustling grass and the creaky balancing of backpacks, Matt Dyer can be heard burping. He burps a lot because he tends to swallow air, a result of recent injections around his vocal cords that caused tremendous swelling. He can also be heard talking about the plants and mushrooms of the forest in a voice that is truly unusual—the bisque-thick Maine accent, evoking abandoned mills and drizzly seas, delivered by shredded vocal cords, transmitting a kind of radio static. Dyer's original voice was changed forever by a polar bear's jaws.

He uproots a mushroom with a thick, foamy stem and a cap like a hamburger bun. "King bolete!" He flashes an intentionally dopey smile at one of his fellow hikers, crossing his eyes and showing his tongue. "The jewel of the French gastronomie! They call it 'porcini' because it goes good with pork."

Dyer, 49, is a lawyer, but he's also something of a naturalist and a druid. The forests are his temples, and all the little living things sprouting out of the ground are his idols. He hikes in leather Asolo boots, his stringy gray hair wrapped in a red bandanna. He has tattoos of birds on his calves and one of the old Norse tree of life, Yggdrasil, covering his back—he adores the Norse myths and the Icelandic sagas.

On Dyer's desk in Maine, where he lives on a country road in a rustic wooden house with the Androscoggin River literally flowing through his backyard, he has sketches of a pair of dancing, multicolored polar bears that will be inked into his forearm. He likes to think there's some kind of kinship between him and the bear that nearly killed him in Labrador, Canada, in the summer of 2013, although he knows deep down that it just wanted something to eat. A friend's theory: It picked him out from the group of seven campers because he snored loudest.

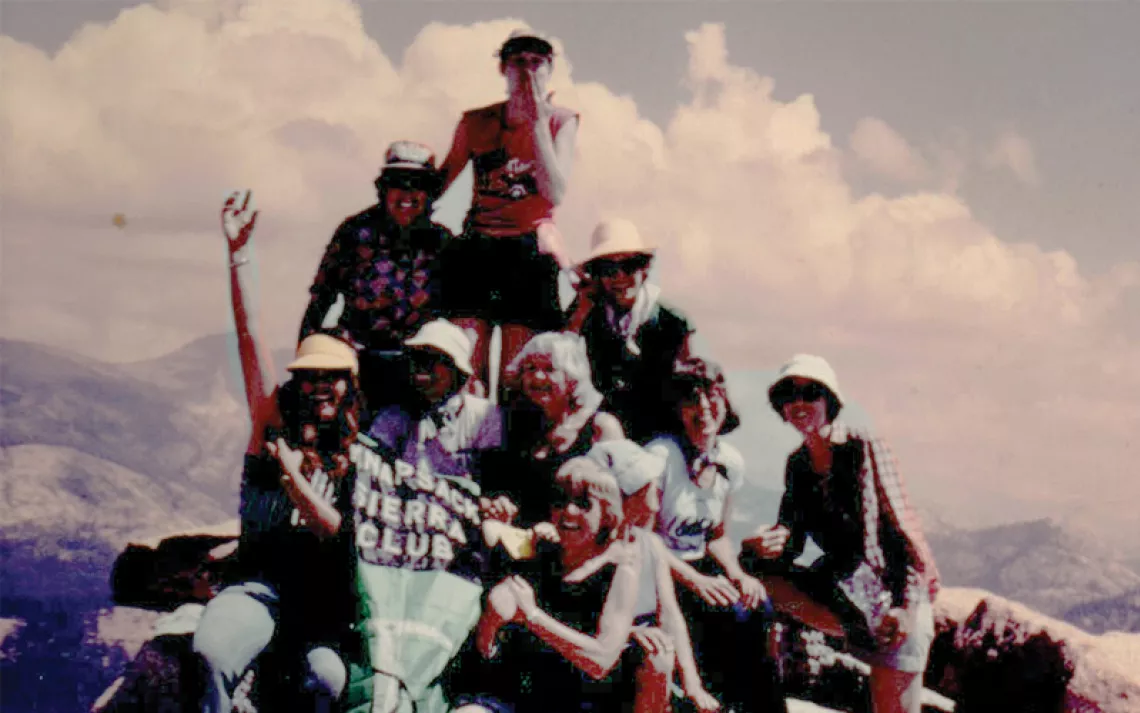

As the 11 hikers round a corner, Dyer emerges from the trees into a granite alcove and burps again—the burps come in waves—then leans over his trekking pole and says, "I feel like I've been doing whip-its." Four of Dyer's companions are especially concerned about his wheezing; they were on the Labrador trip too and now feel naturally protective of him. The other six have known him for barely 24 hours and are already asking him about what happened one year earlier, in the middle of the night, in the wet, wind-whipped Torngat Mountains.

"So it kind of got you like this?" asks Eric, a software technician from Seattle, putting one hand on his left temple and the other on his right jaw.

"It got me just right. If it got me the other way, it would've ripped my eyes out."

"You are a miracle man," says Roberta, a 73-year-old psychoanalyst from New York.

"From a first-responder point of view, it was interesting," says Marta Chase, who co-led the Torngat trip and is co-leading this one. "There were a lot of puncture wounds, but there wasn't a lot of blood. I don't know if you could hear me, but I was talking to Newfoundland on the sat phone and I kept giving you updates."

"I remember voices," Dyer says, but before he can continue, his attention is grabbed by another mushroom, which he taps with his trekking pole. "Slippery jack. You can eat these." He grabs a handful of grass, presses it to his face, and tosses it into the woods. "Smells good right here."

On July 22, 2013, their second morning in the Torngat, Dyer and his fellow hikers saw a mother polar bear and her cub ambling down a beach. The cub looked like a stuffed toy, but the mother had an immense power buried under her fur, and as she walked, her shoulder blades undulated. Mountains shot up behind them. Dyer watched as the pair crossed a deep stream with relative ease, the baby going under and bobbing back out. It was the kind of watercourse that would sweep a human away.

That afternoon, they saw another polar bear come out from behind a boulder and loll its muscular tongue. It's picking up our scent, Dyer thought. Rich Gross, the trip leader, popped off a flare that sent it onto a ledge, where it waited, in and out of sleep, watching the group's camp below.

To Dyer, the Torngat Mountains had seemed familiar before he'd even visited. He'd read about this marooned, unheard-of, practically forsaken land in the Icelandic sagas that he loved, where it was called Markland, the new world. His ancestors had come down to Maine from Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. He liked to read the earthy poetry of the Inuit people, to whom the Torngat Mountains were a sacred land of spirits where the polar bear was a god.

Although he would have preferred the bears he'd seen to be a bit more afraid of humans, Dyer did not want them gone—they were part of being in Torngat Mountains National Park, a place created at least in part for their protection, a place he found intoxicatingly moody. The wind would bring in fog from the sea, then quickly change direction, sending curtains of mist down the mountainsides and back over the ocean. It reminded Dyer of the mist at a cold and wet Pink Floyd concert. He would often glance up to find caribou on the hillsides, and on the beaches there were mossy columns of whale vertebrae that looked to be a hundred years old. The ptarmigan had just brooded out their young. Entire families waddled right up to their camp. He had never been to a place that made humans seem so insignificant. A lot of living and dying on stark display, he often thought in those first two days.

Late on July 23, Dyer went to sleep with bears on his mind. He had seen one on the hills above camp. The way the tents were clustered together, with an electric, bear-deterring fence surrounding them, was a constant reminder that humans could easily become prey.

When he woke up around 2:30 that morning, the first thing he saw—the only thing—was a silhouette on his tent wall. He yelled, "Bear in the camp!" And then it dragged him into the animal world. It was biting his head through the tent, and he covered his head with his hands, but it kept mouthing him, crushing his left hand almost completely and tossing him around like a doll. His head was in its maw, his body now scooped in its arms. He could feel its fur on the other side of the tent fabric. It was tugging on his skull, trying to separate him from the loose outer layer of nylon skin. Tug. Tug. Tug.

The bear flew backward and Dyer with it. They hit the ground as one. He felt a sudden sharp pressure in his chest—his lung collapsing. His jaw cracked in the bear's jaw.

And now it had him clean by the head and was galloping toward the beach. The land went by. His eyes were fixed toward the bear's rolling abdomen, a convexity of wet, creamy fur. It's taking me into the water, he thought. That's what it would do with a seal. It wants to get me away from those people. The bear was exerting itself tremendously now. It huffed hot exhales that flowed over Dyer's nose and ears. The stench of dead fish felt thicker with each of its breaths.

Any moment, lights is out. You are gonna die.

A bone cracked in his skull or neck. There was no pain. None at all.

Nature was kind to make the body like this. No pain in the final moments. I hope it's how everyone goes.

He thought about his wife, Jeanne. She'll be OK. He thought about his dad, a Maine lobsterman, whom Matt, in his earliest memories, would often watch rowing landward through thick, salty fog just after dawn. He's old. He won't be OK. Dyer's father and an uncle would take him fishing for cod right off the docks, or they'd go out in the boat and haul up nets full of squirming slimy critters—monkfish, rockfish, mackerel, skate. Their whole life was a tableau of the zone where the land meets the sea. It seemed fitting that he'd go out as a piece of ocean meat.

The bear huffed harder. He could feel it struggling with him—an oversize, bony seal. They were still moving toward the beach. Any second, the land would go black, the fishy smell would disappear, his mind would end forever.

We all die. This is it. You're going home.

A wave of cool air came off the water. They were getting closer.

Then a flash screamed through the navy blue night and he fell to the sandy grass. Muted voices came from far away. Where'd it go? He couldn't move. He couldn't turn to look. There were giant footsteps somewhere off behind him. He was covered in a clear, gelatinous, fishy-smelling goop. It was gobbed in his hair and streaking the length of both arms. Saliva. The footsteps got quieter, then louder. Somewhere at the edge of his vision, another flash lit the sky. The footsteps went silent.

Pretend you're dead. That's what squirrels do when the cat gets them.

He tried to roll over. Nothing. You ain't moving, brother. Green ground, surging sea, flashes of light in a tent going yellow and gray with dawn. A stranger's hands running over his body. Jeanne—she's gonna kill me. The jet engine rush of a stove. A woman saying into the phone, "We can't move him." And something familiar, a smell from home. Someone, somewhere, was brewing coffee. Smells good.

While the group was getting ready for bed on the night of the attack, trip leader Rich Gross was playing out worst-case scenarios in his imagination. Where would a helicopter land? Where is the flare gun? For 15 years, he'd led Sierra Club outings, and he always thought about this stuff. He looked over the campsite. The tents were packed tight in two rows of three, with the electric bear fence around their perimeter. They were as safe as they could possibly be.

Gross slipped into his sleeping bag, reviewing what he would do if a polar bear attacked. He saw himself grabbing the flare gun, aiming across the bear's snout, where the bear would see the flare but not be struck by it. He saw himself running out to stabilize a body, dialing the number on the satellite phone and giving his coordinates. He fell asleep with the flare gun cocked in his boot, right beside his face.

He woke in the dark to co-leader Marta Chase calling his name. Other voices screamed in aimless fear. He grabbed for the gun, leaped out of his tent, and saw the shape in the distance. About 75 feet away, a shadowy form that could only be a polar bear was carrying a motionless body in its mouth. One of the tents was half shredded, half gone. The electric fence crackled on the ground. He aimed and fired. The flare soared across the bear's path. It dropped the body and sprinted off.

Gross watched the bear flee. It ran and ran, and soon it'd be gone, he thought. But it didn't disappear. It stopped and turned. It was coming back for the body. The body, Gross thought. He knew now that it was Dyer, whom Gross had denied enrollment months earlier for not being experienced enough, then later allowed after Dyer, who'd wanted to go on this trip with an enthusiasm usually reserved for children, had sent Gross photographs of himself on mountaintops in Maine and New Hampshire to prove that he was training for the Torngat trip. Dyer, who'd turned out to be among the youngest and fittest members of the group. And now he was lying dead on some sand and tundra grass, just above the ocean, with a polar bear running back toward his body, wanting to eat it.

He pulled the trigger. A second flare landed just feet in front of the bear. It sprinted off again.

Gross waited for about a minute, until it disappeared into the night, and then ran toward the body with two other men from the group. Dyer's eyes were open and sliding side to side in his head. He was breathing. He's alive.

They carried him into camp and erected the food tent around him. Rick Isenberg, a trip participant from Scottsdale, Arizona, who happened to be a physician, tended to Dyer's wounds. There were punctures from the bear's teeth up and down his arms and on his head and neck. Meanwhile, Chase was on the phone trying to get a helicopter. Marilyn Frankel, an exercise physiologist from Oregon, stood guard on a rock, her hand wrapped around the cocked flare gun, her body rotating slowly in the darkness. After an hour, Isenberg declared Dyer stable, and at 8 a.m., a helicopter came and lifted Dyer and Isenberg away. The rest of the group waited almost eight more hours before a boat picked them up.

And so it fell to Isenberg to call Jeanne Wells to tell her that the worst thing that could happen, the thing nobody thought would ever happen to them, had just happened to her husband.

On that summer morning, Wells was at home in Maine, getting ready to print a photograph, when she saw three missed calls on her phone, all from the same unidentified number. The windows and doors were open. Pollen and light swirled in the garden. It had been less than a week since she'd waved goodbye to her husband as he boarded the Greyhound to Montreal and she'd thought to herself, I should take a picture. I might never see him again. But Wells is a poet turned photographer; she always thinks like that—reading significance into things. At least that's what she had told herself then, and again when she'd come home after seeing him off and found an insurance document sitting in the printer, the page describing his evacuation coverage, and felt a wave of dread.

His decision to go on the trip had thrilled and surprised her. He hadn't done something so exotic since he'd traveled around Europe on a rail pass during college at the University of Maine. Now he liked to garden, to brew mead, to hike, to go to work at Pine Tree Legal Assistance, where he helped the poor, the mentally ill, and the chronically dejected with small day-to-day matters that made all the difference in their lives, like getting the landlord to turn on the heat in the winter. He liked to walk in the woods with their dogs. That winter, as he prepared for the trip, Wells watched him each weekend as he loaded up his backpack with 50 pounds of water, strapped on snowshoes, and set off into the woods for 10-mile training hikes. By the day he left, he was fitter than he'd been in decades.

Her phone rang again, and this time she was there to answer it.

This is Rick, the caller told her. He was on the trip with Matt, and he was a physician.

"Oh no."

"Yes."

"What happened?"

"A polar bear attack, but he's all right."

It didn't seem possible.

How badly was he maimed? she wondered the next day, trying to complete the immigration form as she arrived in the Montreal airport. She could barely read it through her moistening eyes. Soon it was spotted with her teardrops, and she was thinking, Is his face going to be half gone?

His face was not half gone. For the most part, when she met him at Montreal General Hospital, he was intact. To get at Dyer's wounds, Isenberg had cut off his hair, which had been down to his mid-back, but he still had the beard, which the yellow neck brace pushed up from below. He smelled awful. The whole room did, like dead fish, like the bear.

He opened his eyes. From the tangle of tubes and the clutches of the neck brace, he started to cry.

On July 27, the whole Torngat group met Wells at Montreal General. She was allowed to bring them in to see her injured husband two at a time. Gross and Chase went first. They found him with his arm in a cast, his jaw wired shut, his throat filled with tubes. Jeanne told them of the drug-warped dreams he'd been having, something about being dressed up like a mermaid and serving shrimp cocktails to the Mafia in Miami. She told them about how he'd growled at her when she'd asked what had happened, which was his way of saying, "I was attacked by a bear." He was still a bit loopy when Gross and Chase came to his bedside and he asked, with pen and paper, where they were going next year, because he already wanted to sign up for the trip.

On his third night in the Sierra, Dyer is serving people soup. He holds the pot with his right hand and ladles with his left, the one that was pierced by a fang. As he ladles, his hand jerks mechanically, sending soup sloshing in all directions. Nobody says anything about it. After serving the first few of his fellow backpackers, he finds the safe limits of his range of movement and is able to get most of the liquid into the bowls.

When dinner is done, he swigs from a pint of Jim Beam that fits neatly in the back pocket of his pants. "Alcoholic Santa Claus right here," he says, holding out the bottle for any interested party to grab. "I got presents for everyone." But he's not talking about sips of whiskey.

He takes a dozen tiny polar bear figurines from his pocket and passes them out. They are rubbery foam things the size of large beetles. They are all the same except for one, whose mouth opens to reveal an LED light, and he gives that one to Gross.

"Rich, I got this for you. You brought me light when I needed it, so here's a little light for you."

Gross makes a bashful face and clicks his figurine's mouth open and closed. "It's just like the flares that I shot!" He wanders over to a tree and clicks the mouth a few more times, a huge dumb smile on his face. The little bear will go on his desk at work, the prize in a collection of polar bear paraphernalia that he's received from friends and family over the past year.

"Rich, you are a hero!" someone shouts.

"People are always saying," Dyer continues, "that this person saved their life, that person saved their life. I got people right here who really saved my life." He swigs from the bottle and laughs, and the wheezing, grateful, liquor-wet static crackles out over the mountains.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club