A Bigger Camping Tent: Why Is the Outdoor Industry so White?

Every year, I wander the sprawling Outdoor Retailer trade show in Salt Lake City and marvel at the products that eccentric individuals and powerhouse brands like the North Face and Mountain Hardware have cooked up to make getting outdoors even more awesome. And every year, it seems, I run into James Edward Mills, a journalist and social media producer (see joytripproject.com) who stands out at the show by virtue of being one of the few African Americans there. Mills and I inevitably stand beside some huge booth displaying mummy bags or solar GPS chargers and discuss our adventures, eco-concerns, and the question of what retailers and environmental groups can do to make these realms more inclusive. This time, when the show ended, I asked if he'd jot down his thoughts.--Bob Sipchen, editor in chief

I've had the pleasure of attending the Outdoor Retailer show since 1992. Twice each year, summer and winter, I've watched companies come and go. I've seen technologies rise and fall. I've made lifelong friends. And I've raised more than a few glasses to the memory of the dearly departed. I've created a home for myself in the outdoor industry, a place that I love and where I am made to feel welcome.

But over the years, one thing has stayed the same: I continue to be one of the very few African Americans who earn their living in the business of outdoor recreation. Which raises the question: Why?

First, I believe it's important not to get hung up on statistics. There are indeed relatively few people of color who work and play in the outdoors. To understand why, we have to explore issues of cultural relevance. Each of us makes a personal decision, based on our values and belief systems, whether to venture outside or to work at protecting the natural world. A better question to ask is: How can conservation groups and the outdoor industry create more diversity within their ranks and become more relevant to an emerging population of black and brown citizens who will soon become the American majority?

The biggest obstacle lies in our insistence on portraying nature as something far away. Popular language and imagery make the natural world seem remote, distant, and inaccessible. The reality is that nature is all around us. Before we ask people of color to invest their time, money, and energy preserving wilderness areas far from their homes and families, we should first address their appreciation for fresh air, clean water, and open space in their own densely populated neighborhoods.

The great outdoors isn't restricted to the iconic park boundaries of Yosemite, Yellowstone, and the Grand Canyon. Stewardship begins in the natural spaces near one's home. The creation of New York's Bronx River Greenway, for instance, and the push to protect Los Angeles' San Gabriel Mountains by giving the range national monument status are two urban-wilderness projects that have instilled a conservation ethos for a new generation. If we can encourage all people to embrace the environments most familiar to them, they will be more likely to seek out, experience, and ultimately defend those faraway places that they might one day visit and perhaps even call home.

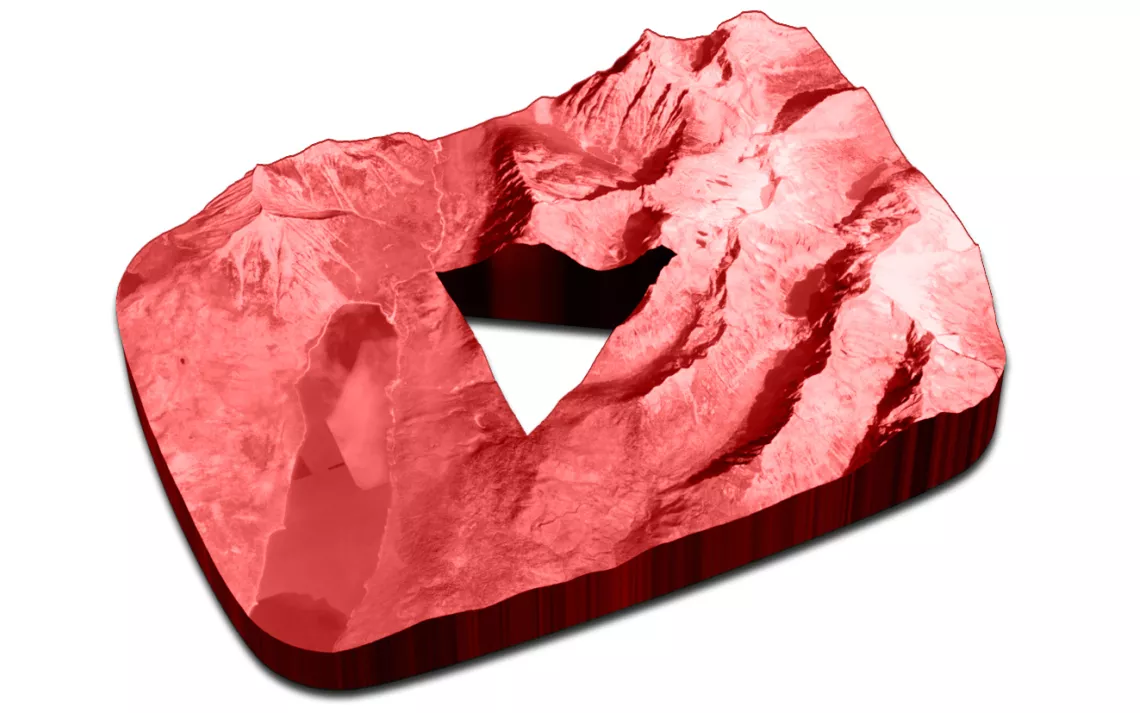

Photo by James Edward Mills

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club