Scientists and Adventurers Team Up to Fight Microplastics

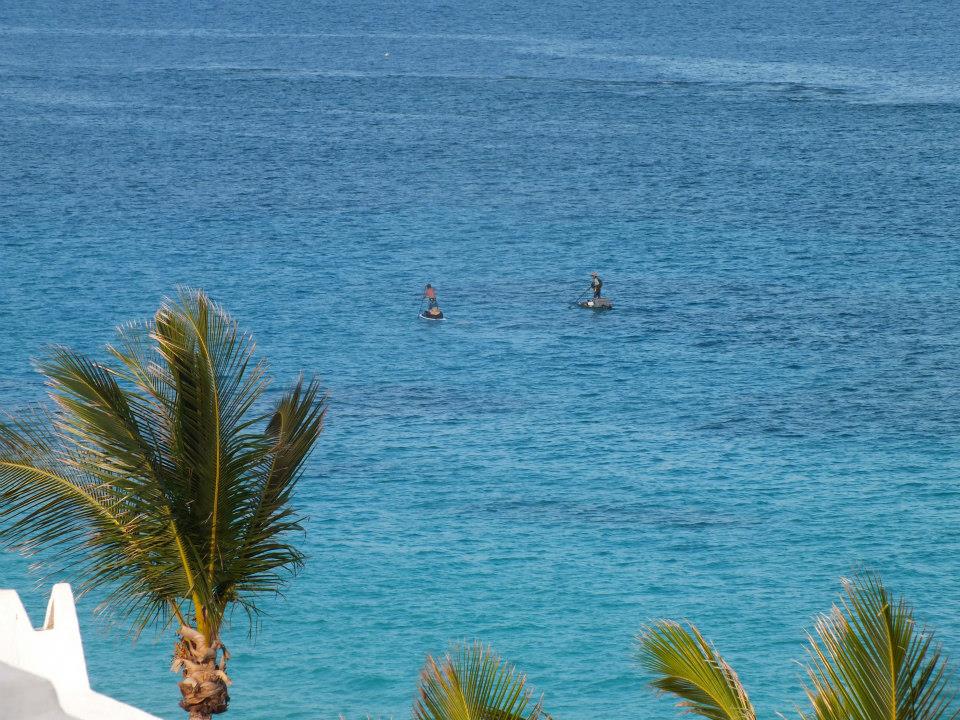

Even only a mile offshore, it was easy to feel vulnerable. Rain gushed and the waves rocked their heavily laden boards. Isolated thunderstorms rumbled around them. On calm waters, paddleboards are as steady as yachts, but as the ocean raged Christian Shaw and his other Plastic Tides crew members wished they were on something more substantial than their ten feet by three feet plastic boards. They desperately paddled to shore and took cover on a small beach. The storm would eventually pass.

This was day three for the Plastic Tides expedition which comprised of five friends on an 11 day, 50 mile paddle boarding journey around the coast of Bermuda. Their mission was to collect water samples to help document microplastic pollution- tiny plastic particles, less than 5mm in diameter that new research shows are effecting marine ecosystems around the world. Most cannot be seen with the naked eye.

Jordan Holsinger, Scientific Manager at Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation (ASC), said that because we can’t see microplastics, most people have an out of sight, out of mind mentality. Yet Holsinger characterized the acute levels of plastic build up in fish as similar to mercury accumulation. “This could have serious consequences, but we are only just now recognizing this problem” he said.

Microplastics come from a variety of sources: degraded plastics, synthetic clothing, even cosmetics. Their small size resembles that of plankton, the organisms that make up the base of marine ecosystems. Unknowingly devoured by filter feeders, the plastics migrate up the food chain, bioaccumulating in larger fish, birds and mammals-- often ending on our dinner tables. The hydrophobic tendencies of plastic attract chemicals like DDT, flame retardants and heavy metals, making each plastic piece a tiny life raft for some of the world’s most harmful chemicals.

Since 2011, ASC has been recruiting outdoor recreationists and explorers to help with field work and data collecting. “We saw a gap between scientists and outdoor communities and we want to connect that gap” said Holsinger. Conservation is often hindered by insufficient scientific information. Yet data collection can be expensive, time consuming, logistically difficult and physically demanding. By mobilizing outdoor enthusiasts, in the year and a half that they have focused on microplastics, ASC has collected water samples from locations in all five of the world’s oceans. Holsinger said their goal is to be a leading force behind microplastic research by completing a comprehensive global scale survey on the distribution of plastics and give scientists the ammunition to move forward.

Christian Shaw is one of the adventurers ASC recruited to help collect water samples. A recent graduate from Cornell University, Shaw is a professional kite boarder and has bathed in salty surf all over the world. He spoke excitedly and passionately about the ocean realm he loves.

“I’m a waterman.” he said. “I’m intimate with the water. Of all the places I’ve been to, Australia, Indonesia, plastic pollution is the common denominator.”

Plastic Tides is Shaw’s first big step in becoming part of the solution. Shaw along with four other friends spent a month total in Bermuda, preparing for the expedition. Their main mission was to raise awareness and collect water samples for ASC and another organization, Plastic Ocean Project, Inc. Shaw said he knew he wanted to do something to protect the oceans. “When we started planning this trip, partnering with ASC was a natural option. We wanted to go on an adventure but also have it mean something. [ASC] has the means to make it more than just a fun trip.”

Bermuda is a unique location because it is the dead center of one of the world’s five ocean gyres. Currents collect thousands of pounds of plastic pollution, creating an ethereal vortex of buckets, fishing gear and bottles. “In Bermuda, to see the true scale of pollution you have to visit the local beaches,” Shaw said. “The tourist’s beaches are pristine, groomed. The local ones tell the real story. Seaweed crusted milk crates and putrid filled bottles cut across the white sand at the water line. Something that scared the team was teeth marks in the plastic. “We kept seeing bite marks in the plastic. The animals are trying to eat this stuff” Shaw says.

Before taking off on the water, the team spent a lot of time hyping their trip on social media and visiting local schools to talk to kids about ocean pollution. “Awareness is a huge part of what we can do” said Shaw. “Besides helping scientists by collecting data, we can also make a big impact just by gathering attention.” Shaw says their consistent use of Facebook, Twitter and Instagram throughout the trip is “a new media approach to environmental activism.” They are also producing a documentary about their adventure.

Trips to local schools proved fun and effective. “One day we packed two of the boards into the truck and went to a school that had a pool. We were in this pool with the boards and like 75 kids and it was kind of nuts. They each got a picture of themselves standing on the board. They were stoked.” During their time on the water, teachers would take 10 or 15 minutes a day to update their classes on the expedition’s progress and what the team was doing. “That’s huge” said Shaw.

During the 11 days of the expedition, most of their time was spent on the water. “We were pretty gnarly, dirty, piraty” Shaw laughs. “We were just beat down the hole time. I had around 400 pound of gear on my board. The other members had about the same. At some points it really sucked.” It took the group at least an hour each morning just to strap everything onto the boards. They would paddle for the day, following a GPS, before stopping on a beach to set up camp for the night. They had no support boat or outside help. “Wind direction was massive” Shaw recalled. “Some days we could cruise. Other times it would take everything we had just to keep moving forward.” On days with a tailwind, they could save a time consuming trip to shore by floating and cooking lunch on their boards.

They collected surface water samples using a small, custom built trawl pulled behind one of the boards for a mile or so at a time. ASC requires a minimum sample size of one luter, so the team used discarded glass blottes from the island to collect what they needed. Plastic Tides collected four liters total, which was as many as they could store on their boards and could afford to ship to Maine to have tested.

In the cozy island town of Stonington, on Maine’s lobster trap riddled coast, Abby Barrows has set up her lab. An independent marine research scientist, Barrows examines the water samples sent to her by adventurers working for ASC. She has been studying microplastics since 2011 but in February of 2013, ASC reached out to her, offering to send her water samples from around the world to help expand her research. She immediately jumped on board. Barrows designed the protocol ASC uses to examine and record microplastic data and has since examined 48 liters of water, with at least as many still in storage, waiting to be passed through her filters.

Her lab is spotless. All the chairs and tables are wiped down. She washes her hands and equipment three times before beginning an assessment. No fleece or synthetic is allowed.“We found through other research that we could easily taint the samples” she says. “We’re looking for nearly invisible pieces of plastic. Traces of plastic can be anywhere so we need to be careful.” Her research is adding to a slowly increasing report of the effects of microplastics.

In 2013, 5 Gyres released a study done in the Great Lakes which revealed extremely high levels of microplastics in the forms of the microbeads used in face scrubs. States like California and New York are now working to pass bills banning the use of microbeads in products sold in their states. Consumer goods manufacturer Johnson and Johnson has said it will end the use of microbeads in its products by 2017.

As researchers find more about the sources of microplastics, solutions to the problem can be implemented. Holsinger asserts that filters could be developed to attach to washing machines and eventually all machines would be built with filters to catch sediments released from fleece. All- natural alternatives such as apricot shells and cocoa beans could be used instead of Polyethylene microbeads in cosmetics.

We live in a plastic world. Years from now, our time will be marked by our reliance on plastic and plastic will never go away. Stuart Coleman, the Hawaii Coordinator of the Surfrider Foundation notes it would be impossible to clean up the massive gyres of debris that blotch the ocean. Yet he says “the problem is not out there, it’s inside of us.” He is referring to single use plastics which we use once, and then throw out. He says that one thing that every group that fights for clean oceans agrees on is the need to encourage for responsible products from companies. “We need to demand, responsible products from companies. Why are we letting companies create a product that we then have no way of getting rid of responsibly? How is it ok for a company to scoop up water then sell it to us at ten times what it’s worth and then leave us with a bottle?” Plastic bags, straws, bottles-- all are used only once and then thrown away. Barrows has similar goals for her research in a field where she says the surface has just been scrapped: “I want this research to be a platform for local legislation changes like plastic bag ordinances. It seems small but local changes turn to bigger changes. Ocean pollution is something that connects people and places globally.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club