Ready, Set, Panic: Japanese Radiation

In January, the blogosphere lit up with fears that radioactivity from Japan's Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant would wash up on the U.S. West Coast. A YouTube video of someone with a Geiger counter detecting what turned out to be naturally occurring radiation on a California beach went viral. So did a doctored photo of beachgoers gawping at a supposedly irradiated behemoth giant squid washed up on the shore.

It is true that a lot of radiation was released when three of the Fukushima plant's reactors melted down after a 2011 earthquake and tsunami crippled their cooling systems. Three years later, as groundwater passes through the basements of the reactors on its way to the sea, it continues to carry away radionuclides like strontium-90 and cesium-137. Four hundred tons of radioactive groundwater seep into the Pacific Ocean every day.

That sounds like a lot, but the vast Pacific dilutes the radiation to background levels long before it reaches our shores. Radiation levels on the West Coast never threatened public health, and have actually declined since the 2011 disaster. And while bluefin tuna caught off California did have elevated levels of radiation, the amount in a standard serving is equivalent to that in one bite of a banana--i.e., not very much.

The real public health threat continues to be in and around Fukushima, where more than 80,000 people are still displaced from a 12-mile evacuation zone. Cooling the damaged reactors generated 90 million gallons of radioactive wastewater, which is being stored in more than a thousand on-site tanks. Hastily built, the tanks leak and spill. Readings taken at the base of one tank found radiation levels high enough to kill a person in four hours. A black sea bream caught at the mouth of the Niida River in Fukushima Prefecture in November was found to contain 12,400 becquerels per kilogram of radioactive cesium--124 times the level considered safe for human consumption.

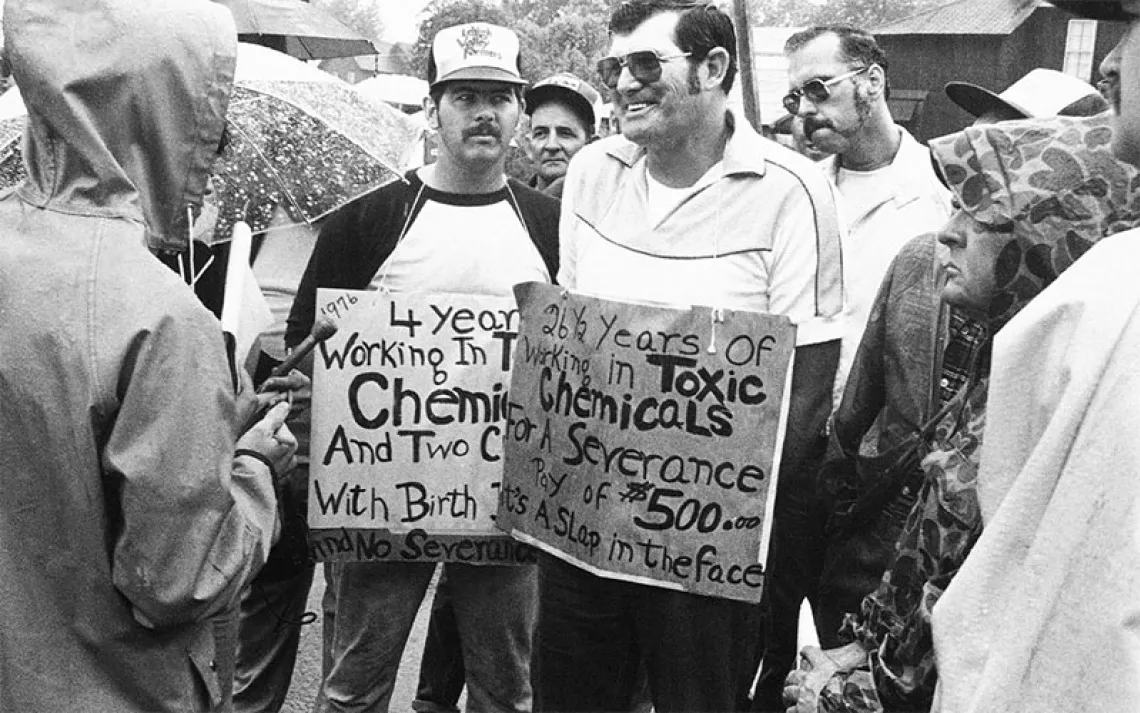

The Japanese government is trying to stem the flow of contaminated water. The most recent plan is to spend $473 million to build a mile-long ring of frozen earth that will keep the contaminated groundwater from flowing into the sea. If all goes according to plan--and why wouldn't it?--the ice ring will be completed next year. Meanwhile, organized crime syndicates have infiltrated clean-up efforts. Operating as labor recruiters, the gangsters send homeless men into Fukushima City to collect radioactive debris and soil, skim their wages, and pay them a pittance.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club