Drop Out

Eden Full is saving the world without a degree

By the time she arrived in Kenya, between her freshman and sophomore years at Princeton, Eden Full had already done the kind of hands-on work that can make a smart, ambitious student wonder whether getting a college degree is all that necessary.

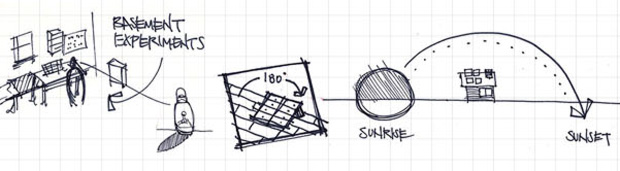

It was the summer of 2010, and she'd come to Africa to test the SunSaluter, a clean-energy device she'd invented in the machine shop in her parents' basement while still in high school. The mechanism rotates solar panels to track the sun by using aluminum and steel strips and heat, rather than electricity, increasing the panels' efficiency by up to 40 percent.

In the isolated village of Mpala, Full met a woman who owned three solar lanterns but could power only two of them with her standard charger. So Full decided to build a solar charging station for the village and headed to the city of Nanyuki to buy parts. She returned a couple of days later to learn that the woman had been trampled to death by a water buffalo while collecting firewood at night without a light. The woman's husband had taken one of the family's working lanterns, and she'd left the other at home with her children. The third lantern remained uncharged.

"She left two kids behind," Full says. "If I'd gotten there earlier, I could have saved her."

In April 2011, Full learned that she had won a $100,000 Thiel Fellowship, which requires recipients to take a two-year hiatus from college to focus on their projects. She decided to leave Princeton and founded her own company, Roseicollis Technologies, to work on putting the SunSaluter to use in the developing world.

"College will always be there for me whenever I want to go back," says Full, now 20. "But what I'm doing has the potential to impact a lot of people and promote the use of solar. We need that more than anything."

Growing up in Calgary, Canada, Full learned from her father, a newspaper artist, that she could do anything. He shared stories brimming with possibilities: She could be an artist, a chef, a musician. She could build robots or cars or space shuttles. She gravitated toward invention even before she could talk.

Full had become fascinated with solar power by age 10, when she built a solar car from a kit and entered it in a science fair. With almost every fair that followed, a new solar experiment propelled her further, and soon she was tackling solar-panel inefficiency. At one point she arranged panels in a Fibonacci sequence, like branches on trees, which are naturally optimized to collect sunlight. Although that didn't work as planned, it sparked her ingenious idea: to use the sun to warm different metals, then harness their heat differential to rotate the panels to follow the sun, like sunflowers do, as it arcs across the sky.

She became so engrossed in her invention that she had a hard time tearing herself away. "My parents would call in sick for me, so I could stay home from high school and work," she recalls. "Teachers didn't understand what I was doing."

Luckily for her, Princeton's admissions officers did, and she enrolled there in 2009. During her freshman year, she gave class presentations about the SunSaluter, and a professor with a research facility in Kenya invited her to work there that summer and test her device.

In Mpala, Full built two solar charging stations using local scrap metal and bamboo. Each cost about $10 (not including the solar panel or battery), and both are still in operation.

"You don't have to be a genius to invent something you're passionate about," she says. "You just have to do it."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club