Sound Off

Will the symphony of the Great Bear Rainforest be silenced by tar sands oil tankers?

Norm Hann on Cornwall Inlet.

"WHOA! WHAT WAS THAT?" Derek Nixon yells, as the telltale pfffft of air blasting from nostrils sounds from somewhere disconcertingly close to us. The rest of our group has stroked ahead to the sheltered waters of a nearby cove, leaving Nixon and me behind on our standup paddleboards, alone on open ocean. We turn toward the noise and see a large brown whiskered head sticking up from the water's surface, maybe 50 feet away. Another pops up beside it.

Feasting bears pay little mind to the paddlers.

Steller sea lions. Big ones.

The pair size us up through inscrutable black eyes for a moment before sinking back into the sea.

We pull our paddles from the water and wait for the heads to reappear. Our 14-foot-long boards suddenly seem very small—the only thing between us and the 1,000-foot-deep ocean and the creatures that live in it. The surface is still. The windless air smells of wrack and saltwater. In the distance, a raven cackles; it could be laughing at us, or maybe just warning us to stay away from sea mammals with large brown whiskered heads.

It's the second day of our paddleboard journey into the Great Bear Rainforest, a place that lends itself to magical thinking, and already I'm starting to get the sense that the animals are trying to tell us things.

Even this now-submerged pair of pinnipeds seem to have a message—or at least a plan. Why else would they announce themselves with startling nostril-blasts before slinking away into the deep? Are they circling below, plotting an assault? Have they been chased away by something bigger?

Minutes pass, and still no sign of them. How long can these beasts hold their breath?

"OK," Nixon says, scanning the water, "now I'm freaked out."

It turns out Steller sea lions can hold their breath for a very long time (more than 20 minutes, I will later learn), which is why Nixon and I finally decide to give up our vigil and paddle for shore. The sea lions eventually do emerge and trail behind us for a mile or so of sporadic spy-hopping. They seem more curious about than afraid of the humanoids who stand on water, but I can't help feeling that maybe they should be afraid—not of Nixon and me in particular, but of humans in general, because some of my species have made plans that could lay waste to their world.

THREE DAYS EARLIER, RAIN LASHED the windows of the small boat that ferried our group of eight wide-eyed travelers along the uninhabited coast of northern British Columbia. We bounced for hours in the choppy channels that slice through one of the world's last great wildernesses—all lush mountains and waterfalls.

Two centuries ago most of the seaboard from southern Alaska to northern California looked like this—mile after mile of rainforest-shrouded coast swarming with whales, salmon, bears, and ancient trees. Today only a few pockets remain undisturbed, and we were headed into the largest of them: the Great Bear Rainforest, a sprawl of wilderness as big as Ireland, isolated by the stormy waters of the North Pacific to the west and the icy spine of the Coast Range to the east.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

The sight of seafaring humans riles the residents of Sea Lion Rock.

We disembarked at Hartley Bay, population 180, a village without roads or cars. Hartley Bay is home to the Gitga'at, a First Nations tribe that has lived off the region's bountiful sea and forest for centuries, maybe millennia.

"My mom kept treating this trip like I was going on a skydiving expedition," John Redpath, a 34-year-old video editor from Squamish, B.C., told me. Redpath was part of the crew of six gung ho Canadians and one equally enthusiastic but utterly inexperienced Yank (me) who'd signed up to join adventure guide Norm Hann on a five-day paddleboard excursion into the Great Bear waterways.

The plan was to spend one night in Hartley Bay, then take a small boat a few miles downcoast, where our paddle trip would begin. But that afternoon, as we headed out with a local Gitga'at fisherman to check crab traps (and harvest dinner), the wind and rain grew fierce—the front edge of a wild storm that would force us to hunker down in Hartley Bay for the next two days.

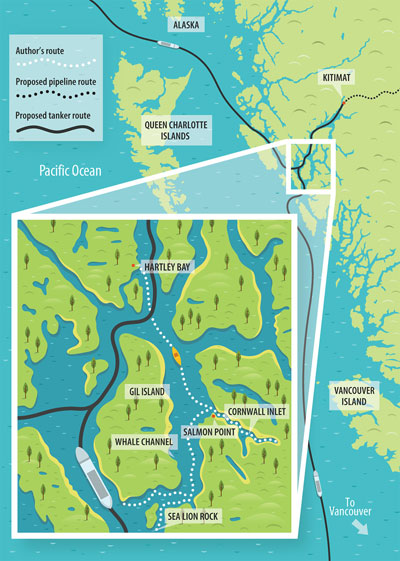

It was precisely the kind of ship-sinking weather that has the Gitga'at and every other First Nations tribe in the Great Bear up in arms over the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline, which would pump Alberta tar sands oil to the nearby port of Kitimat. (See "Battling Big Oil by Land and by Sea," opposite.) From there, a steady procession of massive tankers would haul the crude past Hartley Bay, through a constricted labyrinth of channels, into the North Pacific, and then on to foreign markets.

It was precisely the kind of ship-sinking weather that has the Gitga'at and every other First Nations tribe in the Great Bear up in arms over the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline, which would pump Alberta tar sands oil to the nearby port of Kitimat. (See "Battling Big Oil by Land and by Sea," opposite.) From there, a steady procession of massive tankers would haul the crude past Hartley Bay, through a constricted labyrinth of channels, into the North Pacific, and then on to foreign markets.

Our delay in Hartley Bay had us all antsy to get on the water, so when we finally found ourselves up on our boards—gear lashed, paddles in hand—I let out a "Whoo-hoo!" as I put my head down and dug into my stroke. By the time I looked up, the rest of the group, experts all, had left me far behind. It was a pattern that I would have to get used to.

Our first stop was Cornwall Inlet, a fjord that reaches like a gnarled finger deep into Princess Royal Island. Mountains capped with slabs of granite and carpeted with a thick shag of old-growth rainforest vaulted from the water's edge. Tendrils of mist reached across the slopes where waterfalls sliced through the verdure. Barnacle-armored rocks lined the shore. Rain misted the air, and water dripped from everything.

Hann gathered us near shore and pointed to a ledge in the seaside rock where a small cedar box rested beneath a pictograph of two red eyes—a sacred Gitga'at burial site. The eyes, he said, were meant to watch over the box. An honorary member of the Gitga'at, Hann, 42, has been guiding standup paddleboarding groups through their territory since 2009. Two years ago, determined to raise awareness of the proposed tanker route, he paddleboarded the nearly 250 miles of its entire length, visiting First Nations communities as he went. Although Hann looks like a mountain jock, he speaks with unflinching sincerity about "protecting Mother Earth." Having embraced the Gitga'at worldview, he told us that this entire ecosystem was sacred.

The forest around Cornwall Inlet, like much of the Great Bear, was once slated for logging. Today's threat comes from tar-sands oil tankers.

I could see what he meant. Cornwall Inlet felt more like a temple than any natural place I'd ever been, especially as we paddled up the inlet's namesake river into the forest. Spawning salmon fought their way upstream beside us. Well-used bear trails cut through riverfront vegetation. Cedar needles dripped with pearls of water. About a mile in, we stopped paddling and simply let the current pull us silently back downstream through the verdant chaos. Back in the delta, we hunkered down for the night in a Gitga'at longhouse poised at the edge of the forest.

Ancient Gitga'at spirits—or at least what sounded like spirits—called to us the next morning as we paddled out of Cornwall. We heard a mournful, flutelike noise emanating from the forest. It came again, and I realized it wasn't spirits after all. It was wolves. Nixon, an avid hunter who'd returned calls to honking geese the day before, promptly started howling back. The wolves went quiet. If this was a conversation, Nixon's response had apparently confused them into silence.

In a Gitga'at longhouse, the crew dry their wet gear around a shell-midden fire pit.

At Salmon Point, the last headland before the open waters of the main channel, we glided by a partially eaten salmon carcass on a cushion of rockweed, its freshly bloodied flesh glinting in the soft light. An appropriate offering: salmon carcass on Salmon Point. As we paddled into the channel, the world became engulfed in fog. The air was almost eerily still, and the mirror of the water merged seamlessly with the silver of the clouds.

"It's like paddling through space," I said to Nixon, who'd been serving as my much-needed paddle-stroke coach.

His lesson was interrupted when a new noise shot through the mist—this one resembling the exhale of a punctured hot-air balloon. Everyone froze. Whales. Invisible, but clearly nearby. I stared into the haze but could see only the other paddlers floating weightlessly in a cloud of silver. Then another blast. And another.

"It's almost more magical when you can't see them," someone said. Which was true but not exactly reassuring, given that each of us was floating on a two-foot-wide glorified Boogie Board while animals the size of Greyhound buses, which might or might not be aware of our presence, cavorted around in the impenetrable murk.

The booming underwater vocalizations of humpbacks can be as loud as gunshots.

This channel, I later learned, was named Whale Channel. Clearly, the region's first English-speaking explorers lacked imagination when it came to labeling locations. As long as there were no Ravenous Grizzly Creeks or Killer Whale Coves on the itinerary, I figured I was good.

The next day, we pulled our boards up to the boulder-strewn shore of Gil Island in the early afternoon and headed toward a small house made of milled driftwood. Here, with the blessing of the Gitga'at, whale researchers Hermann Meuter and Janie Wray of Cetacealab have spent the past decade immersed in the acoustics of the ocean. Using underwater hydrophones, they pipe in sounds from the surrounding ocean 24 hours a day. Anytime a humpback sings within a 100-square-mile area, they record the song and file it away.

Wray played us a few minutes of the hundreds of hours of recordings they've saved. Although the bellows, moans, and drip-drop noises sounded to me like a giant stomach in the throes of indigestion, it was easy to imagine the cetacean vocalists harboring uncharted intelligence.

Researchers estimate that 12 percent of British Columbia's humpbacks inhabit the krill-rich waters around Gil Island. Thanks to the whales' distinctive fluke patterns, Meuter and Wray have identified and named 252 individuals. Whale Channel seems to be their favorite place to croon.

"If the tankers come," Meuter said, "we won't be listening to these whales sing."

ON OUR LAST DAY OF PADDLING, we headed south under a brilliant sun into a new reach of Great Bear. By this time, after daily encounters, we were all pretty comfortable around the humpbacks, but that didn't lessen the thrill of watching a pod of six 40-ton beasts explode from the water, monstrous mouths agape. They were using a cooperative feeding technique called bubble-net feeding, in which the whales spiral upward as a tight group from below a shoal of fish while entrapping them in a "net" of expelled air bubbles, gulping down lunch as they simultaneously burst through the water's surface. At one point, the blast of a blow spout erupted 20 feet away, misting our crew.

Gear lashed, paddles in hand, the group glides through the mist in the Great Bear Rainforest.

And then came a new sound: an elephantlike trumpeting booming up from the depths. I looked down and realized that the whales were now directly beneath us. And in case we still had any untapped adrenaline, we suddenly found ourselves surrounded by sea lions. We were nearing their rookery—a cluster of islets packed flipper to flipper—and our presence had their attention. This was, of course, Sea Lion Rock.

As we carefully circumnavigated their haul-out on our knees, the bulls did their best to intimidate us with full-throated roars while bawling harems of cows charged toward us. Their message was clear: Go away.

If the Gateway pipeline is built, supertankers will rumble less than a mile from this rookery. Will the sea lions roar at an oil tanker? Or will the sheer shuddering magnitude simply drive them away? And will these literal place names still have meaning, or will they resemble the names of suburban streets—Heron Lane, Beaver Road—describing what once lived there?

I thought of the risk-assessment study that Enbridge, the company hoping to build the pipeline, had prepared outlining its plan in case of an oil spill at the northern tip of Gil Island, near Hartley Bay—a likely location for an accident given the two 90-degree turns in tight channels that would be required there. Using the Exxon Valdez tanker spill in Alaska as a comparison, the Enbridge study predicts that 150 miles of shoreline would be fouled. It goes on to describe how the spill's "chemical insult" would envelop rocky shorelines and sandy beaches; how it would soak into the soil; how it would coat crabs, plankton, seaweed, and birds; and how oil-fouled fish would be ingested by eagles and bears.

The document includes a timeline that predicts how long it would take the oil to reach Whale Channel, Gil Island, Hartley Bay, the salmon-spawning rivers, even Sea Lion Rock, which it characterizes as "low-value Steller sea lion habitat." The sea lions, I suspect, would disagree.

Northern Lights and a full moon brighten our final evening in the Great Bear. We eat the last of the salmon that the Gitga'at gave us and watch emerald bands race across the sky. Although it is nearing midnight and we are all exhausted, a couple of us look at the lights and then at each other. It's clear what needs to be done. We grab our boards and paddle into the tide-flooded estuary behind our cabin.

The vast silence is broken only by the gentle swishing of our paddles and the occasional splashing of salmon. I look down and realize that my paddle is somehow capturing the aurora to create its own swirling underwater light show. A voice in the dark nearby says something about bioluminescent plankton.

Nixon paddles back and forth, crying, "Look at my wake! Look at my wake!"

Salmon darting from our paddles create streaks of viridescent light, like piscine fireflies. Forget magical thinking—this is the real thing.

A short while later, I'm alone in the middle of the estuary, drifting through the darkness, savoring my last moments on the water, when a loud snort erupts behind me. I turn to see moonlight glinting off the head of a harbor seal, about 20 feet back and keeping pace. I chuckle and reinsert my heart into my chest. It snuffles again, and I realize that this curious seal—like the sea lions and the humpbacks and the entire intoxicating array of wildlife that lives here—isn't trying to tell me anything at all. It is simply breathing.

High tide allows the paddlers to venture up Cornwall River, then drift silently back to the ocean on the downstream current.

Eager to cash in on an ever-expanding global appetite for oil, energy companies in Canada are seeking to build a pipeline that would pump 525,000 gallons of crude oil daily from Alberta's vast tar sands surface mines to British Columbia's coast. If the Northern Gateway pipeline is approved, more than 200 oil tankers annually—all more than 700 feet long and some with a carrying capacity almost two-thirds greater than that of the Exxon Valdez—would ply the narrow, reefy waterways of the Great Bear Rainforest.

The oil-friendly government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper has joined Calgary-based Enbridge, the pipeline's would-be builder, in aggressively promoting the project, which would include a marine terminal in the port town of Kitimat. In February, Transport Canada, the federal agency that oversees marine-safety matters, issued a report declaring that tankers would not pose an environmental threat to the region.

The Sierra Club BC has joined the region's First Nations peoples and other local environmental groups in pointing out that an Exxon Valdez-style accident would decimate not only hundreds of miles of habitat but also the livelihoods of many coastal communities. "The clams, the cockles, the mussels, the crab, the urchins and cucumber, halibut, cod—all that I enjoy will be wiped away if there ever is an oil spill," Clifford Smith, a chief of the Haisla Nation, testified at a federal hearing in Kitimat in January.

Given the Canadian government's pro-pipeline stance, legal experts suggest that the best hope for stopping the project may rest with the First Nations, who have a constitutional right to be consulted and whose opinions carry extra weight. More than 100 First Nations have signed a declaration opposing it, and opposition among B.C.'s coastal First Nations is unanimous. They've promised legal and direct action if the project is approved, setting up a showdown with the federal government in the courts, in the forests, and maybe on the seas.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club