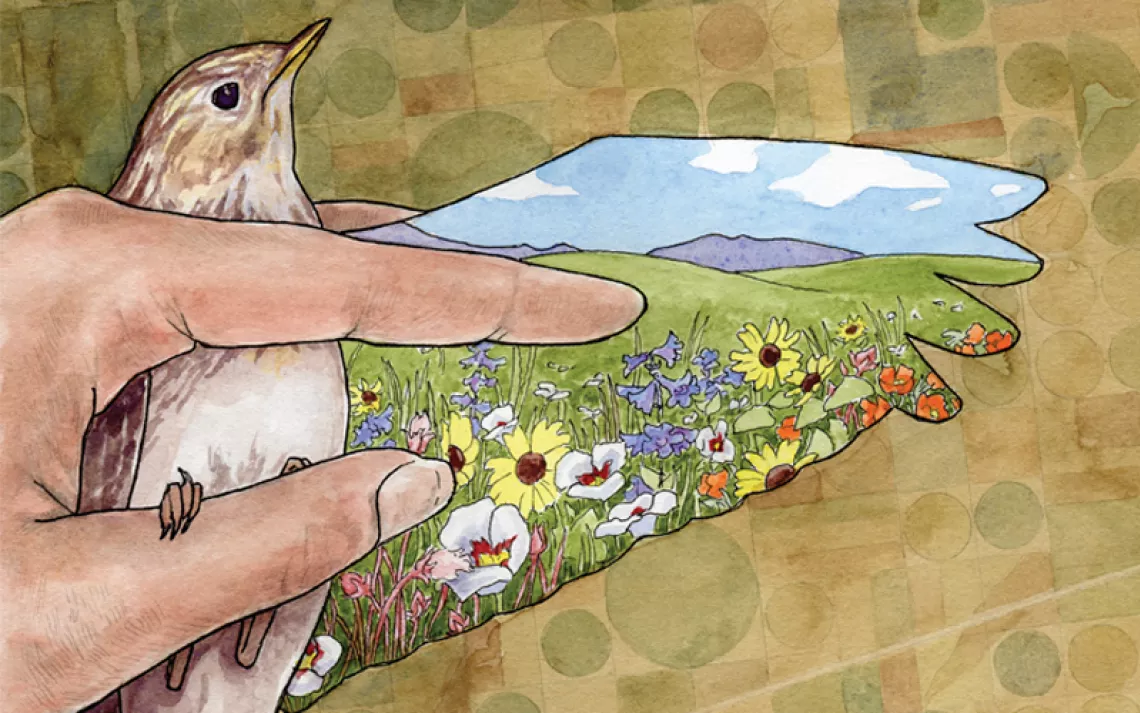

Ghost Bird

In deep Antarctica, a surprising snow kestrel appears

Illustration by Aleks Sennwald

"IT'S A BIRD!" Tim shouts through the fog.

Anywhere else in the world, his phrasing would have struck me as lame and obvious. But here, I drop my shovel into the cache I am digging and look up, frantically scanning the sky—afraid that, like a shooting star, the bird might vanish before I see it.

This is Antarctica. Deep Antarctica—a windswept glacier in the icy interior called the Branscomb, from which the continent's highest peak, Mt. Vinson, rises. Here, no penguins waddle through rookeries, no seals slip between waves, no albatross glide over icebergs. It has been 43 days since I last saw a living creature other than a human. In fact, in my three summers working in Antarctica I have yet to see any animal other than Homo sapiens.

The white body of a snow petrel blends into the dense fog—the outline of its outstretched wings, oversize sails for its delicate body, is barely visible. The bird hovers like a ghost, bobbing on a wave of wind. Its beady coal eyes and obsidian feet are the only signs of color. It circles, etching a carving into my memory.

With the subtle shift of a wing, the snow petrel charts a new course—evaporating into the milky soup that surrounds us. It is gone.

Later, during the daily radio check, I tell our base crew at Patriot Hills, 120 miles to the south, about the unexpected visitor. I am curious how many other birds have been seen at Mt. Vinson. I poll the Antarctic veterans. They tell me snow petrels are sighted at Patriot Hills maybe once a year, but no one has ever heard of a sighting here at Vinson Base Camp. That night, with my hat pulled hard over my eyes to block out the ever-present daylight, I listen to the rat-tat-tat drumbeat of graupel against my tent. The image of the petrel keeps resurfacing. Our encounter was brief—less than two minutes—but the lone bird swoops back and forth across the canvas of my closed eyes.

Despite their delicate physique and thin veil of feathers, snow petrels live in Antarctica year-round. They spend much of the year at sea, then at breeding time fly up to 200 miles inland to reunite with their mates and scratch out nests high on rocky outcroppings. Back and forth the birds fly from the land to the ocean, where they snatch krill, mollusks, and fish from the icy waters. The food sustains them and their chick until the fledgling is ready to fly.

I burrow deeper and listen to the wind grow to a whine. I think of the six plane rides it took to get here—Jackson to Salt Lake to Dallas to Santiago to Punta Arenas to Patriot Hills to Vinson. In a few weeks, we'll retrace our journey back to warmer climes. And when we get home, we'll share photos and stories and brag about our ability to survive in this stark, inhospitable place.

But the petrel, it will stay.

Right now, though, I find myself wondering whether I really have any business on this ice cap. If it weren't for the minus-40- degree-Fahrenheit sleeping bag I'm swaddled in and my 800-fill down parka, I wouldn't last more than a few days. And if my survival was at stake, I'd quickly pluck the petrel's feathers to warm myself, then eat its carcass raw. These are the thoughts that creep in during Antarctica's relentlessly sunlit summer nights.

Sorry, little bird. I meant to say, thank you.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club