The Second Man: A Father Shows His Son the Ropes

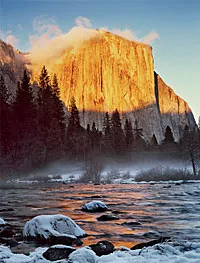

A father and son climb El Capitan

Photo by Robert Ankrum

I HAVE A PICTURE OF MY SON, Ian, dangling from a boulder when he was three. Rock climbing is my career, and I hoped it might become part of his life too, so I taught him the basics. But during Ian's teens, baseball and snowboarding were more his style. By the time he finished high school, our trophy list of climbs together was solid—but short. Only when he moved away for college did he start climbing regularly. Before long he was leaving me in the dust on many outings.

Recently, Ian hinted that he wanted to do a big climb together. Maybe something in Yosemite Valley. Maybe El Capitan. At first I balked at the thought of all the logistics and responsibility, but I quickly realized that it might be one of my last chances to one-up my son—or "share my expertise," as I liked to phrase it. I'd done a lot of big walls; he'd done none. Ian, now 27, would be completely out of his element.

On a face like El Cap, youthful gymnastics play little role. We'd inch up a smooth vertical face on nylon ladders attached to steel hooks or tiny blades wedged in hairline cracks. Security would come not from poise on footholds and finger grips—the kind of climbing Ian knew—but from understanding anchor systems and believing in the gear, especially the rope, which can feel as thin as a thread as you trust your life to a long strand of it. At best, we'd advance 500 feet per day, and the climb would take almost a week. At night, we'd camp in the sky.

I explained all this, thinking it might scare him off. But it only fueled his enthusiasm. We arrived in Yosemite in late August.

From the valley floor, El Capitan doesn't look real. The face is two miles wide, 3,000 feet tall, and as sheer as a skyscraper. Its surface is cleaved into angular facets that reflect silver and gold in the Sierra sun. When you gaze up from the meadow, the wall's hazy higher reaches seem dreamlike in their distance.

To climbers, El Capitan is a rite of passage. The opportunity to climb this mythical rock with my son made me feel privileged and thankful, but also a little stressed. I hadn't done a big-wall climb in quite a few years, and we'd had almost no time to practice. Ian would need to learn a lot—and fast.

Our route, called Zodiac, was steeper than vertical from base to summit, with almost no ledges. After each 100-foot rope length, we anchored to preset hardware on a blank wall and stood in slings, hauling our bags up behind us.

Ian's job as second man was to use mechanical ascenders to climb the lead rope and retrieve the gear I'd placed. This sounds simple but isn't, and it was fun to watch him work through the problems of navigating a tensioned line. Sometimes he'd get so encumbered with the retrieved gear and various loops of rope that he could hardly move. Watching from above, I took care not to correct him too much, or to laugh. I took comfort in the way he stayed calm—and in the fact that he tied plenty of backup knots. By the third day, he'd gotten it down to a system, and we were in a groove.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

Near the top there's a long and tricky traverse. In wall climbing, horizontal passages are a challenge for the second man. Usually, you rig a sort of back rope and carefully tension yourself across—a slow, often-tangled affair. But in the right situation, if you're feeling lucky, you can just go for broke and swing.

Clipped to a fixed piton and looking out at the long section of horizontal rope, Ian yelled up, "Any reason I can't just cut loose?" I was impressed with his pluck, but could tell it would be quite a ride. Still, it appeared to be free of obstacles, so I leaned out, smiled, and gave him a thumbs-up.

Ian looked to his right, then back to the piton he was hanging from, then to his attachment points. I could see his mind working as he triple-checked his knots. Finally, he adjusted a sling or two, took his weight off the piton, and unclipped.

The wall was steeper than he'd calculated, so instead of staying close to the rock and running across, he shot diagonally out into space, legs kicking, on that very skinny rope, way, way up on his first big wall. When the swinging finally stopped, my son was right where he wanted to be. He planted his feet on granite and struck an open-arm pose, as if embracing the whole of Yosemite. His war whoop echoed across the valley, so loud I could feel it in my chest.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club