Wilderness Diplomacy

Can photos of America's natural wonders inspire a cultural cease-fire?

Outside a house he's building for his family and surrounded by his children, Muhammad Jan, a 46-year-old builder and plasterer, displays photos of Biscayne National Park in Florida and Glacier National Park.

|Landscapes by Ian Shive

THE IMAGE IS FAMILIAR, a variation on a postcard theme: the Teton Range during a storm, backlit and snowcapped, with the cottonwood-hemmed Snake River shimmering in the foreground. The photograph appears on the cover of Ian Shive's 2009 coffee-table book, The National Parks: Our American Landscape, which is itself a variation on a familiar theme: a hardcover visual celebration of 33 federally protected parks, monuments, preserves, seashores, and recreation areas.

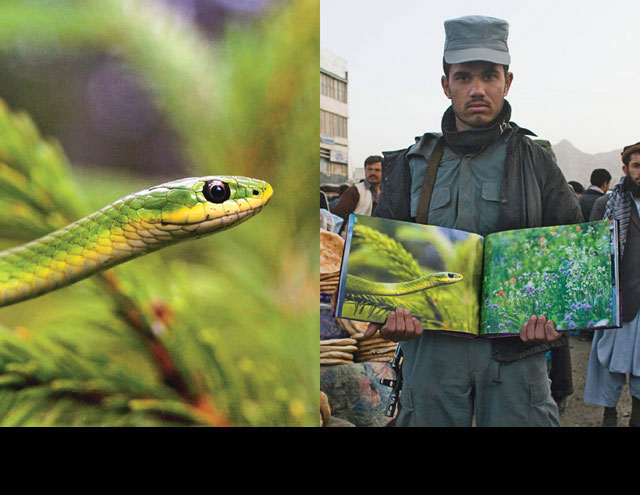

A snake in Acadia National Park, Maine, and wildflowers in Glacier National Park, Montana, shown by Aliulla, 22, a Kabul policeman. Photo by Ian Shive (left).

But as with any media, the photo's emotional message varies depending on viewer and context.

Give it to a historian, and he or she might note that the shot pays homage to one of Ansel Adams's best-known black-and-whites, taken in 1942 from a similar vantage point in similar weather at a similar time of day—and that it serves as a reassuring reminder of how little that sacred landscape has changed in the half century between shutter clicks.

Palwasha Amir, 42, is the mother of eight children. 'I like this book,' she said. 'I like nature.' Opposite: Arches National Park, Utah. Photo by Ian Shive (right).

But put it in the lap of a middle-age Afghani woodworker—whose visual imprint of the United States presumably tilts toward underdressed starlets, flaming skyscrapers, and Abu Ghraib poses—and the image of that Wyoming massif becomes much more complex. If Shive is right, it whispers to the woodworker that the American soldiers patrolling his streets come from a country that abounds in natural beauty; that its citizens take pride in that beauty; and that they have the good sense and common will to preserve it.

Twelve-year-old Apana Zahor shows photos of a coyote in Yellowstone National Park and a Channel Islands National Park trail. Apana is one of seven children. Her name means 'almond' in Pashto.

Now push it further: Take a portrait of the woodworker cradling the Teton photo as it appears in Shive's book, show it to a U.S. audience, and let them make yet another connection. Let them consider the notion that a man who embodies the concept of "foreign" might in truth feel a kinship with their homeland, might agree that it's a place worth protecting. And then let them wonder what that man's life is really like.

Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. Opposite: 'I'm happy to have this book,' said Kabul woodworker Hamidullah, posing here with his brother Najibullah and nephew Samiullah. 'It will be good for our kids and guests. Some pictures remind me of Afghanistan.' Photo by Ian Shive (left).

The woodworker, it turns out, is a 54-year-old named Hamidullah; an ethnic Pashto, he goes by only his first name. Beside him in the photo are his brother Najibullah, 51, and Najibullah's son, Samiullah, 19. They live in Kabul. Hamidullah had 11 children, but 4 of them died young. He earns about $500 a month. "I'm happy to have this book," he said. "It will be good for our kids and guests. Some pictures remind me of Afghanistan."

Shive calls it "wilderness diplomacy"—the notion that nature photography can help bridge the divide between mutually distrustful cultures. "The idea started by accident," he said. "I had a friend who was going to Dubai, and she took a couple of copies of my book as gifts. She sent me back pictures of people looking at the books—college students. They told her that they'd never realized America looked this way. They thought it was all New York and Hollywood."

Quadratullah, a schoolteacher in Kabul, Afghanistan, displays photos of a fox on Santa Cruz Island in Channel Islands National Park, and of a sandstorm at Stovepipe Wells Sand Dunes in Death Valley National Park, both in California. Photo by Ian Shive (left).

Shive, 32, is a guy who gets things done. At age 19, he moved to Los Angeles, where he got his first job at a film studio, claiming he was 23. Within five years, he was a marketing executive for Columbia Pictures, working on the releases of such hits as Spider-Man and Memoirs of a Geisha.

On weekends, he pursued another passion: nature photography. "It was my escape from L.A., from the glitz," he said. "The second I got off work on Friday, I'd fly to Yellowstone or some other park to shoot photos. It turned into an obsession. It just felt right."

Hazmatullah (left), 61, with his son Rahmatullah at their onion shop at a produce market in Kabul. After they sell their onions, they will return to their village in the Nangarhar province in east Afghanistan. Hazmataullah displays photos of Potato Harbor on Santa Cruz Island in Channel Islands National Park, and of Badwater Basin in Death Valley National Park. 'I have never seen the ocean with my own eyes,' Hazmataullah said. 'So beautiful.'

As his portfolio improved, he hooked up with a stock-photo agency. Soon, royalty checks trickled in. Three years ago, he made the risky decision to become a full-time photographer. His Hollywood training helped: "I applied everything I knew about marketing to my photography business."

Nasir Khan (left), 26, and Sami Mallalai, 28, in Kabul's financial district, not far from the bank where they work. 'I can see this man has spent years taking pictures for this book,' Nasir said. 'He traveled a lot.' They hold photos of Mount McKinley (left) and Mount Foraker in Denali National Park, Alaska. Photo by Ian Shive (right).

Late last year, Shive made the wilderness diplomacy idea happen by partnering with Roots for Peace, a nonprofit based in San Rafael, California, which was already receiving donations from Shive's publisher, Earth Aware Editions. Primarily focused on removing land mines from and planting crops in war-ravaged countries, Roots for Peace has done work in 28 of Afghanistan's 34 provinces. It plans to distribute 25,000 paperback copies of Shive's book this year to Afghan students; the first shipment of 1,000 went out in March.

"Ian's images of America's wildlife, forests, and flora will resonate with Afghan culture," said Roots for Peace founder Heidi Kuehn, who delivered copies of the book to Afghan's provincial governors at a gathering in March. "It represents what we have in common rather than what separates us."

Ian Shive, on the job on the summit of Mauna Kea, Island of Hawaii. Photo by Suzanne Gotis.

Once his project gains momentum, Shive plans to reverse the flow by traveling to Afghanistan, shooting its most scenic wild places, and making a book of those photos to show to Americans. He hopes that someday a photo of the shock-blue lakes of Band-e-Amir (which the Afghan government enshrined in 2009 as the country's first national park) will end up in the hands of, say, a New York City cop. And maybe someone will shoot a portrait of that cop displaying the image of the lake, and Shive will arrange to share that photo with a woodworker in Kabul. See if it makes him wonder what the cop's life is like.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club