Everybody Hates Chuck Schwartz

The head of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team is just a scientist trying to do his job (probably).

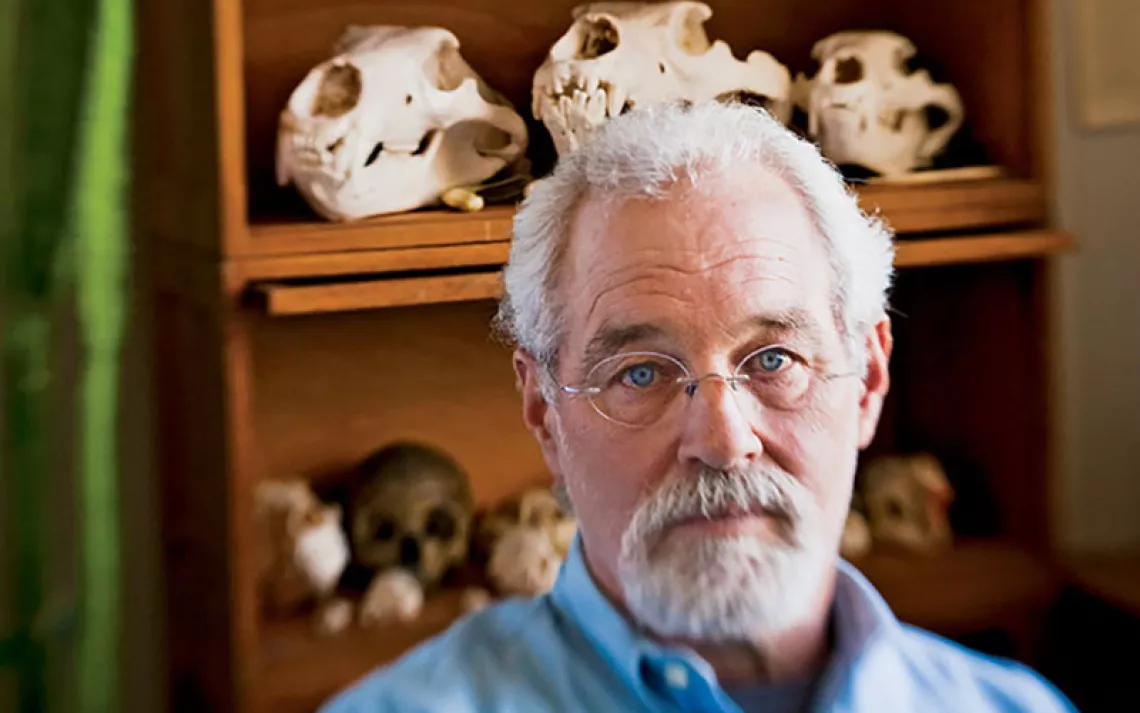

Chuck Schwartz in his office in Bozeman, Montana. The bear skulls in the background came from as far away as Russia and Africa. | Photo by Moe Witschard

Shannon Podruzny pulls the car over just before a mama griz comes loping out in front of it, a pair of cubs shuffling behind her like heavy-footed soldiers. It's a cold September day in Yellowstone National Park, and the bears seem oblivious to the light hail falling as they move along the west slope of Mt. Washburn. Although Podruzny has been a grizzly bear researcher for more than a decade, she suddenly transforms into a tourist. "Cool!" she says, rummaging for her camera. "I never get to do this!"

A healthy stand of whitebark pine on Mt. Washburn, in Yellowstone National Park.| Photo by Richard Perry/New York Times/Redux

Podruzny and I are in the park to visit a transect of whitebark pines a few hundred yards off the road. She monitors the health of several dozen stands each year, looking for evidence of the two scourges currently tag-teaming whitebark pines across the West: the invasive fungus known as white pine blister rust and the native but proliferating mountain pine beetle. The high-elevation trees appear on bear researchers' radar because of their protein-rich seeds, a favorite snack of the black and grizzly bears in the 20-million-acre Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), which is about 10 times the size of the national park itself, fanning out from it in all directions. In the fall, when they're putting on pounds for a five-month hibernation, Yellowstone's bears gorge on whitebark pine nuts filched from squirrel cone caches. In a good year, these seeds can account for more than half of a grizzly's caloric intake. But with beetles and blister rust wiping out whitebark across the GYE, environmentalists are increasingly concerned about maintaining healthy, resilient bear populations without the seeds, while some land managers dispute the seeds' importance.

Podruzny shoots photos as the three bears cross the road. They're heading straight for our transect, which forces her to nix our field trip. "Oh well," she says, "I'd rather they use it than we do." As the grizzlies clamber up the mountainside, undeterred by brambles, I ask Podruzny what the bears are likely to find when they get to the study zone. "I don't know," she says, "but they sure won't find any pine cones."

In the fall, seeds from whitebark pine cones are a key source of fat for Greater Yellowstone's grizzlies as they prepare to hibernate. | Photo by Richard Perry/New York Times/Redux

Podruzny's boss is Chuck Schwartz, a professorial wildlife biologist for the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the head of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST), a joint effort of eight wildlife-related agencies. Seated before a cabinet of bear skulls in his office in Bozeman, Montana, Schwartz wears rimless glasses and a dress shirt featuring images of hunting dogs and birds. He agreed to be interviewed only after I repeatedly assured him that I was uninterested in debating the politics of grizzly bears or their status under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Yellowstone's grizzlies lost their endangered-species status in 2007, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared its multidecade bear-recovery plan a success, citing a healthy population of around 600 bears, up from a low of 136 in the mid-1970s.

The Sierra Club was among several organizations that challenged the delisting in federal court—citing, among other factors, the serious threats facing whitebark pine. ESA protection prevents development in grizzly habitat and provides funding for research, monitoring, and education. It also prohibits hunting and keeps final management decisions in the hands of federal agencies, rather than state and local officials, some of whom argue that grizzly bear populations have risen to the point where "harvesting" should be allowed. In September 2009, a federal judge in Montana reinstated the grizzly's ESA protections, but Fish and Wildlife has appealed that ruling, and a final decision on the matter is expected later this year.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

Gary Hamilton/National Geographic Stock

Schwartz doesn't want to talk about any of that. He is a scientist—as he repeatedly reminds me—and therefore takes no sides in the heated debates that typify most conversations about wildlife management in greater Yellowstone. In fact, the IGBST was specifically created to provide a neutral, scientific voice in such disputes. The study team dates back to the early 1970s, a time when Yellowstone grizzly numbers were falling precipitously because of the National Park Service's adoption of a "natural management" strategy. Between 1968 and 1971, park managers shut down the open garbage dumps where many bears had come to feed, a move that proved unpopular with both Yellowstone's viewing public and its pioneering grizzly researchers, Frank and John Craighead.

The Craigheads pushed for gradual closures of the dumps, predicting correctly that their abrupt removal would cause the bears to wander into populated areas seeking food, provoking more encounters with humans. Indeed, contact with people during the dump-closure years coincided with a spike in bear deaths, and the Craigheads' public beef with park managers helped put an end to their research in 1972.

The view from Yellowstone's Avalanche Peak reveals a hillside of dead and dying whitebark pines, their needles red from beetle and blister rust damage. | Richard Perry/New York Times/Redux

The following year, that controversy gave birth to the IGBST, a coalition of scientists from the National Park Service, USGS, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, and the U.S. Forest Service, plus the fish and game departments of Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and the Wind River Reservation. The team is charged with monitoring grizzly populations and bear-research trends but is exempt from making policy decisions that might actually have an effect on the animals. In the world of U.S. wildlife management, the IGBST is ambitious and unique—there's no equivalent group for wolves, cougars, or other headline-making megafauna.

"We bend over backwards to see that the science remains neutral," Schwartz says. "If the science supports one side, so be it. If it refutes the same side, so be it. We let the numbers do the talking."

But there's a paradox at the heart of the IGBST concept, since the group's singular authority on grizzly behavior, diet, habitat, and population size puts its data at the center of every imaginable bear-centric controversy, from the ESA delisting to park campground closures to strategies for dealing with problem bears.

Red means dead: The needles soon fall away, creating the gray ghost forests now seen throughout Greater Yellowstone. | Richard Perry/New York Times/Redux

The fracas over whitebark is a recent example. Last July, when U.S. Fish and Wildlife announced that it would review whether to designate the tree a threatened or an endangered species, environmental groups did a collective fist-pump. (Protecting grizzly food sources, such as whitebark pine, is a tenet of the Sierra Club's Resilient Habitats campaign in Greater Yellowstone.)

Two weeks later, however, a group called the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC)—which consists of top-level policymakers from U.S. and Canadian public-lands agencies, and which relies on data from Schwartz's IGBST—issued a report that downplayed the importance of whitebark seeds to the bears' diet. "Grizzly bears are generalist omnivores," it read, "and they consume alternative foods when whitebark pine seeds are not available." The report named Schwartz as an adviser and press contact, which didn't win him any friends among environmentalists, many of whom accuse federal agencies of de-emphasizing the importance of whitebark in order to bolster the case for delisting grizzlies.

Vertical larval galleries in a pine tree's bark are a sign of mountain pine beetle infestation. | Richard Perry/New York Times/Redux

"The study team is made up of people, and people have values and worldviews," says Louisa Willcox, a senior wildlife advocate with the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) who's worked on grizzly issues in Greater Yellowstone for 25 years. "Those values and worldviews affect the science. . . . What I have been increasingly concerned about is how enmeshed the study team may become in the political agendas in the ecosystem."

Sitting across from me in his tidy office, Schwartz defends the research summarized in the IGBC report. As his team's public face, he spends a lot of his day explaining the group's data to nonspecialists, and he speaks in the deliberate, patient tone of a veteran schoolteacher.

The IGBC, he explains, relied on 24 years of data correlating grizzly population patterns with whitebark pine cone counts. Broadly speaking, half the years between 1986 and 2005 were lousy cone years, with an average of fewer than 10 cones per tree (and often approaching zero), while the other half were good, with somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 to 50 cones per tree. Plotting bear data against cone data, Schwartz's team detected only negligible decreases in both cubs per litter (to 2.0 from 2.2) and adult-female survival rates (to 0.93 from 0.95) following years with low cone counts. Neither trend is enough to affect the overall growth of the region's grizzly population, Schwartz contends.

Schwartz's detractors maintain that this data ignores, as it were, the forests for the trees. Simply considering cone counts on healthy trees isn't enough, they argue, because the total number of healthy trees is shrinking exponentially. In response, the IGBST points to annual numbers of cub-producing females, which have remained steady throughout the past decade even as stands of cone-producing trees have dwindled by half.

Environmental groups, wildlife management agencies, and IGBST data all point to a grim future for old-growth whitebark pine stands in and around Yellowstone. Drier climates and warmer winters enable pine beetles to thrive in larger numbers and at higher elevations, feeding on cambium and spreading a fungus that clogs trees' resin ducts. Schwartz notes that a healthy understory may eventually replace these stands but acknowledges that it's likely to take decades before the young trees produce cones. He cautions that it's inappropriate to infer too much from IGBST data about a hypothetically whitebark-free future—a prediction vigorously emphasized by environmental advocates.

"I don't know that I find data from several isolated bad cone years reassuring," says Sierra Club western regional director Steve Thomas. "Let's see what 10 consecutive bad cone years look like before we make any assumptions, because they're coming."

Likewise, all parties seem to agree that diminishing whitebark stands will force grizzlies to go farther afield in search of food, which is likely to increase the species' encounters with humans and thus its mortality rate. A jolting 41 grizzlies died as a result of human contact in the first 10 months of 2010—up from an average of 19 per year throughout the 2000s. Schwartz points out, however, that an increase in human-bear contact does not always lead to an increase in bear deaths. Inside the park, for example, where bear-proofing is a religion, there's little correlation between poor whitebark years and human-caused bear deaths.

Walking me through these points, Schwartz laments the hyperbole that various camps put out in the wake of the IGBC report. "I've always felt like science was sort of the hub of reality," he says a bit mournfully, "but now it's just more rhetoric and spin." Several environmental blogs, for instance, have hinted none too subtly that a high-profile grizzly attack outside Yellowstone last summer could be blamed on the increasing scarcity of whitebark. Seemingly unprovoked, a female with two cubs killed one camper and mauled two others at a National Forest campground seven miles outside the park's northeast entrance. As Schwartz and others point out, however, the attacks occurred in late July, several weeks before the cone maturation in fall generally entices grizzlies to feed on whitebark.

What the spat over whitebark illustrates is the uniquely awkward position in which Schwartz and company often find themselves. In a sense, the IGBST is always somebody's bad guy.

"He is welded at the hip to the Fish and Wildlife Service's delisting agenda," the NRDC's Willcox says of Schwartz. "He's their water carrier."

Conversely, the conservative blogger Michael Dubrasich (whose Western Institute for Study of the Environment routinely lashes out at the Endangered Species Act) recently described the IGBST as "allied with radical environmental groups...with an extreme political agenda that taints any 'science' they do."

Such polarized and contradictory attacks come as no surprise to Kerry Gunther, who heads Yellowstone National Park's bear-management office and is the study team's National Park Service representative. "When we were at low population numbers, the loggers, miners, ranchers, and motorized-recreation people—they all thought our research methods were bunk," he says. "Then our data started showing the population recovering, and the environmental groups and bear advocates turned on us. All of the sudden we were these government bureaucrats you couldn't trust."

Mark Haroldson is nobody's bureaucrat. Surrounded by four computer monitors in a cluttered office next to Schwartz's, Haroldson is a rumply, soft-spoken guy who wears jeans and flannel to work. After growing up watching National Geographic documentaries about the Craigheads, the wildlife biologist has spent more than 25 years trapping and tagging grizzlies, first along the Montana-Canada border and now for the IGBST. These days he handles more databases than bear traps, embodying a rare combination of spreadsheet savvy and old-hand backcountry cred, and his name appears on more published IGBST papers than that of any other member of the team.

Spend enough time sitting at conservation's giant, misshapen debate table, and it's easy to suppose that those seated around you lack your commitment or concern. But as Haroldson gives me a short tutorial on various radio collars, his passion for the work emerges. When I ask whether grizzlies start to feel like livestock after so many capture-and-collar missions, he looks positively wounded. "Once you deal with a bear personally," he says slowly, "you can never consider them a barnyard animal. Every bear is unique. And that uniqueness grabs you."

When our grizzly encounter prevents us from checking on her research transect, Podruzny opts instead to give me a long lesson on pine beetles and blister rust. We bushwhack through a few mixed stands on the side of Mt. Washburn, examining the beetles' crook-shaped larval galleries, the ocher-stained branches that betray an early rust infection. Whitebark pine is a charismatic species, and the few healthy trees we find are gorgeous: graceful and curvaceous, with thick, pillowy needle clusters.

At one point, Podruzny mentions that there are two methods for assessing the extent of a blister-rust infection. Some researchers simply count the number of spiral-shaped cankers on a tree's branches, while others prefer a qualitative index that charts the cankers' severity. We stop to examine a dying pine, its once-bright needles faded to a dull red. "Of course," she says, "we're scientists, so we can't agree on anything."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club