Slickrock Redemption

It's easier to get into Heaps Canyon than to get out

After you rappel 75 feet into Zion National Park's Heaps Canyon, there's no going back.

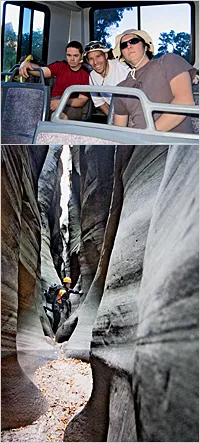

In the depths of Zion National Park, Ray Miller searches for redemption.

He trudges forward with more than 40 pounds of wetsuit, rope, water bottles, and other equipment strapped to his back. His friends, Casey Hunter and Jon Rockwood, trail a few yards behind.

Dust thickens the 104-degree air on this June day. The sun beats the stone monoliths, the cottonwoods, and the hikers' shoulders. The three walk past skittish whiptail lizards and up white sandstone switchbacks into the belly of Zion, into Heaps Canyon.

It was just such a June day in 2006 when Miller left a companion for dead, far down in the twists of Heaps.

As the morning sun reached over the Zion Canyon Visitor Center on May 31, 2006, sleepy-eyed tourists waited in line for permits to explore the park's secret alcoves--the Subway, Keyhole, Pine Creek, and other treasures. Among the throng were Miller and his friend Nathan Cresswell. A chance encounter with Nolan Porter, an acquaintance of Cresswell's, had sparked a plan: The three would tackle Behunin, a classic slot canyon that offers simple challenges for moderately experienced canyoneers.

All three fit that description, more or less. Porter had been canyoneering for five years, but a lightning strike had robbed him of feeling below the knees. He was plagued by chronic pain and sometimes needed morphine to control it.

Miller was a good climber but not an advanced canyoneer. Nevertheless, he deemed himself skilled enough for what he thought would be an easy day trip.

Cresswell was to lead the expedition. He had plugged the coordinates for Behunin Canyon into his GPS and had a guidebook and a description of the canyon he'd found on the Internet. He'd also printed out a map of their destination--but only of the immediate area. Failing to bring a map showing Behunin's larger context, he later said, "was definitely my worst mistake."

After getting their permit, the three packed food, water, and gear for a day trip. They left soon after dawn the next morning, slogging up the 21 switchbacks of Walter's Wiggles. Bypassing the popular but vertigo-inducing Angels Landing, they continued past spiny yucca and into stands of pine, pausing briefly to chat with a backpacker before moving on. According to Cresswell's GPS, Behunin Canyon appeared to be farther up the trail. What he didn't know was that Zion's layers of canyon and cliff make pinpointing a particular spot on the twisting trails a challenge. In fact, the entrance to Behunin was just paces from where they had spoken to the backpacker.

The three saw a canyon with black mineral stains that Cresswell thought he recognized from a description of Behunin. There was also some fixed protection to rappel off. "This must be our canyon," said Miller.

They roped up and started down. In canyoneering, after a rappel is complete, you pull the rope from its anchor. The snap of the falling rope signifies one thing: The only way out is down. "Once you pull that rope, you're committed," Porter said. "There's no going back."

They forged on, rappel after rappel. After six hours, the end should have been near, but the canyon wound onward. As the sun arced over the steep canyon walls toward twilight, they began to question whether they were in the right place. But they pushed on, and Heaps Canyon opened its jaws wider.

Serious canyoneers aspire to canyons like Heaps. It demands technical rope skills, climbing ability, and swimming. Most who attempt it spend the night and finish on the second day. Among Heaps's many hazards: falling rock, heat exhaustion, and a nearly 300-foot free rappel at the end. The greatest danger, ironically, is the cold. Even when outside temperatures top 100 degrees, sunshine fails to warm the frigid pools in its narrow depths. That's why most canyoneers tackling Heaps bring wetsuits or drysuits.

Even on the warmest days, sunlight fails to warm the many pools at the bottom of Heaps Canyon. Swimming them without a drysuit can be a ticket to hypothermia.

Bo Beck has been a search-and-rescue volunteer at Zion for 14 years and has been through Heaps a dozen times. The danger of hypothermia, he noted, lies not only in lowered body temperature but also in the diminished mental capacity that comes with it. "That canyon is not a spot you want to be lacking in physical and mental capacity," he said.

With the sun disappearing, the dry canyon the adventurers had expected turned out to feature a series of pools. Miller and Porter swam through the first of many potholes, while Cresswell avoided the water by scurrying up a ledge and rappelling down past it. Miller, who was now freezing and said he had to keep moving, came back to help Cresswell finish the rappel. Porter was already hypothermic--because of his injury, he couldn't retain body heat well. He too needed to move.

Cresswell refused to continue. He could see more water ahead and knew that getting wet with night coming on was the perfect recipe for hypothermia. He chose to stay dry and hunker down for the night.

"Oh hell," Miller thought. He sprinted around in an effort to keep warm. Then he heard Porter calling for help. He packed up a rope and ascenders--devices for climbing back up a rope--and headed down the canyon.

Porter was perched on a damp log jammed just above the water in a narrow section of the canyon. Balancing on that thin bit of safety, he had used an emergency kit to start a fire. Now that he was out of the water, he claimed to be fine, but Miller knew better. "Nolan, we need to get you out of there," he said. "If you don't get out of there, you're going to die."

Getting Porter to dry land meant first getting him back into the water. Porter balked. Finally Miller coaxed him back through the icy potholes. Using the rope and the ascenders, the two inched their way back to Cresswell. The three gathered what branches they could find, spread out a tarp and an emergency blanket, and huddled around their fire for a fitful night's sleep.

The next morning they hiked up to the ridge in a section of the canyon known as the Crossroads. They hoped to be able to climb out but found only an insurmountable cliff.

Now it was Porter who refused to keep going. "Rule number one that any Boy Scout will tell you is that if you're lost, stay put," he said. Miller, however, was determined to get out. For this 24-year-old, waiting for help would be the ultimate humiliation: He saw himself as a rescuer, not the rescued. He eventually agreed that Porter should stay put, but tried to convince Cresswell that together they could find help. He saw himself as Porter's hope for survival. "My job was to save Nolan," he said.

Cresswell, pulled between the two, finally decided to follow Miller. "I figured Nolan would probably be all right, so I made a choice to go with Ray because I figured he had a better chance of getting through the water with two people," he said.

Porter set to work constructing a distress signal by tearing up his reflective emergency blanket and placing the pieces around a beacon fire. He kept another piece to hold up as needed. The contest of wills between Miller and Porter had taken its toll, and their separation was not an amicable one. Already missing his morphine, Porter settled in to wait.

With no drinking water and only an orange for food, Miller and Cresswell made their way back into the frigid water. At least they had a neon poncho Porter had given them. They came to a 30-foot rappel, descended, and pulled the rope. There was no turning back.

Dozens of sandstone potholes dimple the floor of Heaps Canyon. Seven or eight of them are "keeper" holes, where smooth sandstone offers little traction. In years when snowmelt and rainfall are low, the water drops to levels that make it nearly impossible to get out. Luckily, it had been a wet year.

Miller and Cresswell wound through the labyrinth, Miller getting somewhat ahead. He exited one difficult pothole and slid down to the next, out of Cresswell's view. He didn't know that Cresswell, unable to find the hidden exit, assumed he was in a dead end. Cresswell cried out in panic "like a wounded dog," Miller said.

But Miller had already moved on to the next pothole. "I can't come back up," he yelled to Cresswell. "You've got to get out or you're going to die! Come on! Go! Pull out! You can do it! Just kick!"

Cresswell's pleas for help turned into silence.

Miller waited on a small ledge, water rushing over his feet, for what felt like eternity. Faced with hypothermia and believing his companion to be dead, Miller decided that he had two choices: wait and risk dying himself or leave immediately to increase his chances of survival. "I kind of just left--turned my back and ran away," he said. "It was the worst feeling I've ever had in my life."

As Miller's second day in Heaps Canyon gave way to night, rescuers had already found Porter. A helicopter searching nearby Refrigerator Canyon had spotted the reflection off the pieces of his emergency blanket and signal fire. They dropped supplies and a radio; Porter told them that Cresswell and Miller were farther down the canyon.

Meanwhile, Miller had established a routine: walk, crawl, pass out. When darkness fell, he tore branches from nearby bushes to make a bed. As he lay down, he heard the impossible coming from behind--footsteps.

Cresswell had survived. Miller ran to greet him, grabbing his gear and helping him into the branches, where the two lay shivering. They did little talking; their silence came from exhaustion, but also from deeper wounds.

Only later would Miller learn what had happened. After Miller left, Cresswell summoned what little strength he had to find the exit to the pothole and throw himself over a rock. He talked himself into getting into the next pothole. Then the canyon began whispering inside his head: "Just give up." The voice nearly won, but Cresswell found the will to go on by thinking of his family, particularly his brother, who was graduating from high school that same day.

Safe in the branches, Miller and Cresswell heard the wonderful whir of a helicopter. Soon they saw it and waved the neon rain poncho Porter had given them. The helicopter dropped a supply bag. "Is this the lower Heaps party?" the dropped radio squawked into Cresswell's ear. For the first time he understood where they were and what danger they had been in.

"Ray, we're in Heaps, man," Cresswell said in disbelief. "We're in Heaps."

They had to decide whether to wait 12 hours for rescue or to continue by themselves. Being so close to the end, they chose to finish on their own the next morning. But first they requested extra rope and drysuits. They would not move a step without drysuits.

Zion search-and-rescue contacted Bo Beck to help guide Miller and Cresswell out. Early the morning of the third day, Beck hiked up to the Upper Emerald Pool, where Heaps Canyon ends, and made radio contact. Based on the pair's description of their surroundings, he determined that they were only 200 to 300 yards from the last series of rappels. "I just went, 'They're almost done. They're out of there. They didn't even need the drysuits,'" Beck said.

He talked Miller and Cresswell through a short but spooky climb and coached them down the last set of cliffs, ending with the dramatic, nearly 300-foot free rappel. Crowds of tourists huddled around the pool cheered as Miller and then Cresswell made their way down the rope. Rescuers had picked up Porter in a helicopter that morning, shaking his hand and telling him he had done the right thing.

Today another crowd is gathered at the Upper Emerald Pool as three helmeted figures appear high above at a notch in the rock. First, Casey Hunter rappels down and untangles a nest of rope. Jon Rockwood follows. Finally, Miller descends. This crowd cheers too. Tackling Heaps Canyon "the right way" has restored Miller's confidence in himself and his abilities. As for his first experience there, he says, "it feels like a lifetime ago."

A year and a half after the original ordeal, Miller happened upon Porter at Waterfall Canyon Climbing Park in Ogden, Utah. There he finally acknowledged that Porter had made the right choice by staying put. "I could see this kid had learned so much from that time," Porter said. Miller went on to take summer jobs as a canyoneering guide at a resort near Zion. "When you mess up, you want to redeem yourself," he said. "You don't want that hanging over you."

Still hanging over Miller, however, is his abandonment of Cresswell. The Heaps experience hit Cresswell hard. Soon after returning home to Woods Cross, Utah, he woke up in the middle of the night in a cold sweat, his heart beating furiously. The emotions he had suppressed while in the canyon flooded into him. He has since overcome the trauma and is hoping for his own chance to confront the monster that nearly claimed his life. "I have to slay that demon, you know?" he said. But he wouldn't do it with Miller: "I felt I made the choice to go with him through this water to help him out, and then he went by himself and chose to save himself," he said.

"Self-preservation was just way easier for me than saving somebody else," Miller said. "That's got to be the hardest thing. To admit that is just ridiculously hard. I don't know if I'll ever forgive myself completely for leaving him." That kind of redemption, he said, will have to come not from Heaps Canyon but from deep within himself.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club