Lost & Found

The mystery of Louise Teagarden is not what became of her but why she disappeared

It's a fantasy many desert hikers share that one day they'll look under a ledge and find an intact olla brimming with wild apricots. Peering into dark corners for clay pots or arrowheads just becomes automatic. Vicki Spear had acquired this habit from years of wandering in the Santa Rosa Mountains above Palm Springs, California. One day in 1991, she and a companion were boulder hopping up a little-used draw when she glanced up and saw stones stacked by hand, reinforcing a rock shelter.

Naturally, Spear had to look. Most caves yield nothing, so she certainly wasn't expecting what she found. Years later she says of that moment: "You don't want it. It can't be happening."

Want it or not, it was hers: a skull, an arm bone, and the rest of a skeleton tucked in a shredded sleeping bag. Rodents had scattered the cave's contents, but lying near the body was a hand-drawn map and a calendar from a Whittier bookstore, with dates marked off from December 17, 1959, to February 20, 1960. Judging from a box of Kotex also found in the cave, the bones were a woman's.

Spear made a decision that may seem peculiar to the rest of us but is in keeping with the unwritten laws of the Santa Rosa Mountains. Odd things turn up in those hills, and the finders keep their mouths shut. Spear had found headless skeletons from a long-ago Indian massacre and didn't tell authorities. Another local found a skull with a bullet hole in it far in the backcountry and let it be. "The thing up here is to leave things alone," Spear says. The cave dweller had died a long time ago, so the discovery seemed to Spear more like an archaeological find than a crime scene. Probably no one was looking for the woman. Spear and her friend walked back to the trailhead, agreeing to keep silent.

We know the story: A young man walks off into the wilderness, never to return except into the ranks of folk heroes. Most famous are Christopher McCandless (the subject of Into the Wild) and Everett Ruess, an artist and writer who disappeared in the Utah canyonlands in the 1930s. Both helped shape their own mythology, leaving behind reams of Unabomber-like ideology and colorful alter egos: Alexander Supertramp and Lan Rameau, respectively.

This time, however, the wilderness wanderer is not an adolescent joyrider but a mature woman who turned 40 in her rock tomb. Her name is Louise Teagarden. She invented no aliases, and if she wrote a manifesto, it hasn't survived. Two brothers out deer hunting, John and Bill Sloan, came across her discarded diary in the 1960s near where her car was found. It was full of girl things, they said, worries about family and relationships. (The brothers have since died, and no one knows what became of the diary.) While the McCandless and Ruess stories grew louder and more public over time, Teagarden's has retreated into privacy and silence. Almost no one--even in Palm Springs--knows her name.

"When Auntie Louise disappeared, it was just hush-hush," says her niece Barbara Barnes. "Nobody in the family wanted to talk about it."

Some of what we know about Teagarden comes from a family history written by her father, Albert. She was born in 1920 and grew up in a close middle-class family living here and there in Southern California: Hollywood, Highland Park, and Whittier. Of three sisters, Teagarden was the only one who never married and thus was expected to be her family's helper--coming home as an adult to nurse one sister through an infected cat bite and her father through prostate cancer.

Teagarden had discovered the freedom of the wilderness as a child on family camping trips to Bryce Canyon, Yosemite, and Sequoia National Parks. Sometime around 1949 she moved to Ribbonwood, a tiny settlement on Highway 74--also called the Palms to Pines Highway, the serpentine drive depicted in chase scenes in the 1963 comedy It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. She moved into the storeroom of the Ribbonwood general store, a little ramada where travelers would stop to purchase curios (Teagarden made buttons from manzanita wood) or a Nehi soda.

The proprietor, and Teagarden's roommate, was Wilson Howell, a vegetarian proto-hippie who kept a huge garden, befriended skunks, and lived mostly on sunflower seeds. He was also friends with local Indians, who taught him how to make soup from native yucca blossoms. Up here Teagarden was accepted, even though she was in a relationship with a woman, not a common arrangement in the 1940s. Mountain resident Harry Quinn knew Teagarden and remembers her girlfriend, Betty Moore, an amateur archaeologist who'd show up at digs in Barstow and Tehachapi driving a military jeep equipped with a trailer, cots, backup fuel, and water tanks.

To this day Quinn is impressed with Teagarden's survival skills. His opinion is backed by his own outdoors cred: He taught wilderness survival in the Army, worked in remote Alaskan camps as a geologist, and survived crashes of three helicopters and two fixed-wing planes. Teagarden knew where to find wild strawberries on the back side of the Santa Rosa Mountains, he says, and could locate tiny seeps where she'd insert a straw and an hour later have a quart of water. She'd disappear on solo backpack trips for weeks at a time and stop by the Quinn family cabin on her way home. While skirting questions about where she'd been, she did let Quinn--then just a boy--study her hand-drawn topographic maps, with their penciled notations of elevations, ranches, locked gates, and the all-important springs and streams. A series of circles she'd drawn along a trail corresponded to a mesquite grove--a native food source she may have learned about from Howell.

Video: "Lost and Found: On the Trail of Louise Teagarden"

Teagarden's family may not have shared Quinn's respect for her backwoods knowledge. Her choices baffled them; some would later tell authorities that she was "moody." Her father, at least, loved and struggled to understand her. In his memoir, Albert often mentions dropping by Ribbonwood to visit "our Louise." Anxiety creeps in as she becomes more insistent on her solo walkabouts. "Now I must tell of Louise's years of wandering away from home," he writes.

In 1954, two years before his death from cancer, Albert wrote that his daughter "holds to the thought that she is happier there [the Santa Rosas] than she would be anywhere else and that she would not fit into the social life of any city or town. So we must be content to wait, hope, and pray that she may lead the life that will make her the happiest."

In December 1959, Teagarden told Howell she was driving to Hemet to go Christmas shopping. When she failed to return, a search turned up her car parked at an abandoned gold mine in Garner Valley. Teagarden had drained the radiator and placed the radiator cap on the driver's seat, just as Howell had taught her to do in the days before the common use of antifreeze. To Howell, that meant she was coming back.

From the Gold Shot Mine, Teagarden hiked through head-high thickets of red shank along the Pacific Crest Trail and picked up one of several paths leading toward Palm Canyon, an area pocked with grinding holes and other reminders of Cahuilla Indian occupation. The cave where she settled was low ceilinged and just big enough to stretch out in. Above her, the sweeping agave-dotted plateaus of the desert merged into the snowy flanks of the Santa Rosa peaks. The brushy crowns of palm trees peeked from a nearby oasis that was like the set of a jungle movie, with deep pools (good for bathing), fat lizards, and vines. At night the lights of Palm Springs sparkled some seven miles below her shelter.

Moving-in day must have been a relief. While she had never fit in with her peers from the city, out here she was more able than any of them.

Temperatures dropped to the teens, setting records for cold. Days before she disappeared, it had snowed in nearby Idyllwild. But Teagarden knew how to keep warm; the newspaper accounts of her disappearance called her a "competent woodsman." Anyway, it was probably better being chilly in a cave than at home with her family for the holidays. Her father had died three years before, followed soon after by her sister Virginia. Her girlfriend Moore had moved away. Now her mother's health was declining, and Teagarden was again under pressure to come home and care for her. After all, as her surviving sister surely pointed out, Teagarden had no responsibilities. At an age when others were raising families, she was running around the mountains like a make-believe Indian, black braids flying.

Her staples--Zwieback and Hershey's bars--must have soon run out. New Year's 1960 brought more snow, but Teagarden survived and survival was perhaps a goad to her, a challenge to stay on. The last date crossed out on her calendar was four days after her 40th birthday on February 16. Teagarden was likely thinking in her final days about her mother and sister and how she'd let them down. Howell had respiratory problems and relied on her for trips to the doctor. He and others were undoubtedly upset with her for disappearing. The longer she stayed, the harder it was going to be to explain her absence--plus, spring in the desert comes early. Easier to stay for now.

Teagarden's remains might have stayed hidden for another 30 years if it hadn't been for Spear's low-life hiking companion. Unbeknownst to her, after their discovery he had doubled back to the cave and taken Teagarden's skull. Days later a sheriff's deputy found it in the cabin of a local who had likely purchased it from the grave robber. The skull triggered a coroner's investigation that led officials to Teagarden's shelter.

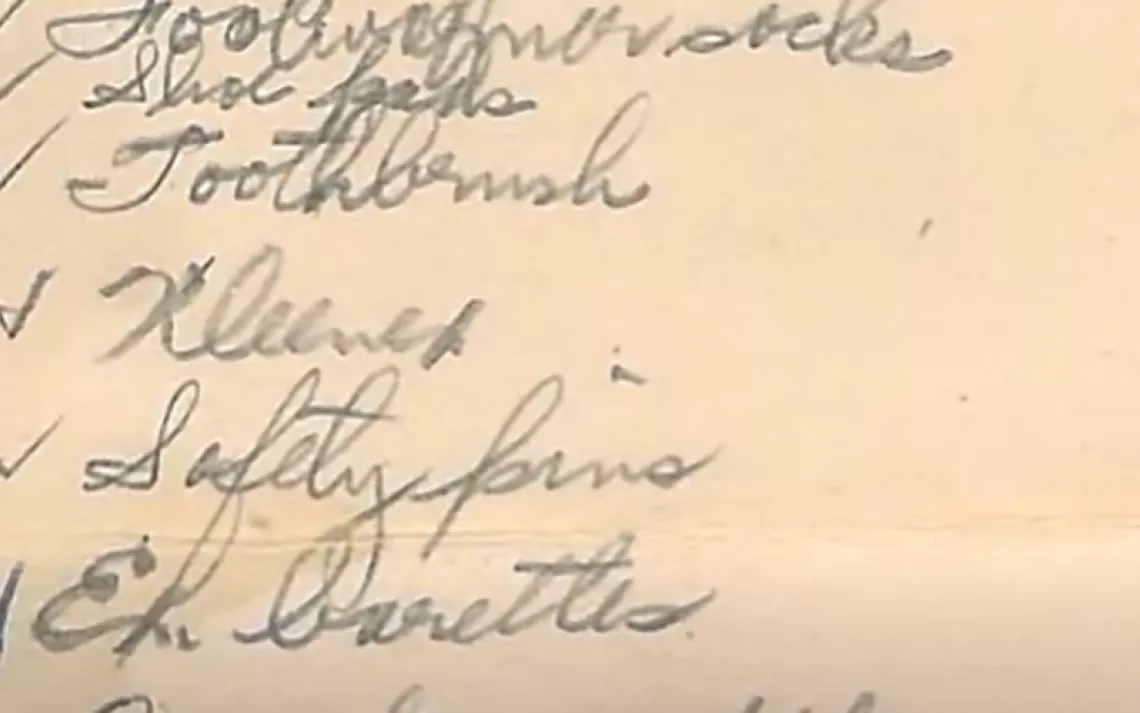

Authorities had no idea, however, to whom the remains belonged. The riddle was solved when Barbara Barnes--who was only 15 when her aunt vanished--produced a wedding album with Teagarden's signature. The handwriting sample matched the writing on a list of supplies found in the cave.

The coroner listed the cause of death as unknown. There were no broken bones, no signs of trauma or foul play. But there was this tantalizing find: The teeth found in the cave showed an unusual staining pattern on the front central incisors. "Staining of this type is not commonly found in modern populations," wrote forensic anthropologist Judy Suchey.

In another surprise, an enlarged deltoid tuberosity--a muscle attachment in the arm--suggested a musculature more like that of an Aleutian kayaker than a 40-year-old suburban woman. The discoveries suggest that Teagarden might have lived like a primitive, growing strong from foraging and staining her teeth on chia, agave, and mesquite.

In mid-winter, though, cactus would have been the only wild food available to her. So she may have died of starvation. Or, as her niece and mountain residents speculate, she could have succumbed to a snakebite, appendicitis, hypothermia, or suicide. Whatever the cause, we know how Teagarden's final solitary walkabout ended. Death looms so large in these tales that we forget it's not the main point. The point is the urge to go into the mountains or desert alone, a necessary and creative response to being human. That's why Ruess and McCandless have spawned so many imitators--young seekers who follow Ruess's steps across the redrock or trek to the Alaskan school bus where McCandless lived. They would understand something about Teagarden, something her father and girlfriend also knew. She wasn't running away; she was going toward something.

Teagarden had wanted to live like a native on the land, and she'd done it. She owned it all--the seeps at Madwoman Springs, the basketball-size grinding holes near Bullseye Rock. The beauty of the backcountry too was hers. The last things she would have seen before she died were stone pools full of snowmelt and dense thickets of cholla cactus wearing halos in the low winter light. No one knows what her last days were like. Maybe she was freezing, fevered, or depressed. She may have regretted many things about her life, but going to the mountains was probably not one of them. It was the thing she did right.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club