Burned Out on Burning Man

Can the artistic free-for-all go green?

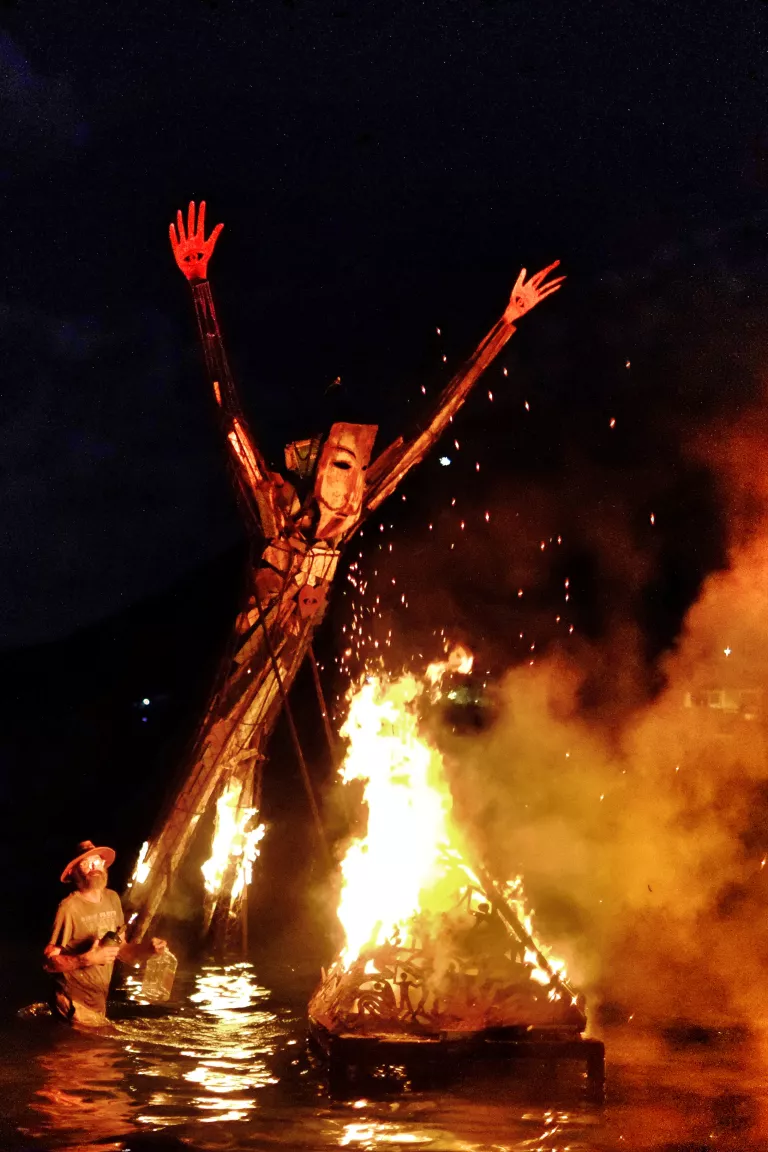

POWERED BY 2,000 GALLONS OF PROPANE and 900 gallons of jet fuel, the mushroom cloud thundered across Nevada's Black Rock Desert, incinerating a 99-foot-tall wooden oil derrick and deluging thousands of art- and party-loving spectators with a 2.4-gigawatt blast of heat and light. Loudspeakers blared a dark, off-key rendition of "The Star-Spangled Banner." Eight towering, humanlike metal sculptures representing the world's religions bowed in worship before the flaming spectacle, said to symbolize the impending crash of our fossil-fuel-addicted civilization.

The Burning Man festival is notorious for such grandiose displays. Volunteer coordinator Kachina Katrina Zavalney was not amused.

"It made an obscene mess," she said, the frustration in her voice echoing a growing philosophical rift.

For years "burners" have been trying to draw lines of ethical behavior in the desert sand. As last summer's Crude Awakening performance broiled the night sky with petrochemical flames, some confronted a question whose relevance resonates far beyond the annual encampment: With life on Earth now clearly at risk, how much waste, pollution, and hypocrisy can we humans justify in our pursuit of art, education, freedom, and--yes--fun?

NORTH AMERICA'S BEST-KNOWN COUNTERCULTURAL gathering, Burning Man attracts more than 40,000 participants annually. For eight days ending each Labor Day weekend, a flat, white, dusty badland becomes an off-kilter outpost of civilization: Black Rock City. Attempting to explain the event is like describing Disneyland to a Martian. It's an odd mixture of yoga and body painting, fire spinning and skydiving, throbbing rave music, mazes, profligate drug use, and, at least once, an enormous bar carved into the innards of a three-story-tall wooden structure in the shape of a rubber duck.

Devotees band together to create themed campsites organized around common interests such as raw vegan food, Dr. Seuss storytelling, pedicure parties, and massage. Money is banned and bartering discouraged. At last year's event, college-age kids pedaled around handing out homegrown apples, their contribution to the festival's freewheeling "gift economy."

The burning started in 1986, when artists Larry Harvey and Jerry James built and spontaneously torched an eight-foot-tall wooden statue of a man at San Francisco's Baker Beach to honor the summer solstice. The fire attracted a crowd, and the artists turned the moment into an annual ritual. Within a few years, hundreds were gathering to immolate "the Man," who had grown to 40 feet tall. When park police declared the fires too dangerous, the artists moved their event to the Black Rock Desert, a prehistoric lakebed northeast of Reno. Isolated and off the grid, the desert turned out to be a fine canvas for radical self-expression, a bureaucracy-free zone where people could revel in almost unlimited freedom. Anything was possible--gunslingers pulverized stuffed animals at a drive-by shooting range, and oddly decorated "art cars" careened across the desert.

As the event grew, organizers created a road system and banned firearms. While some protested the demise of anarchy, others commended Burning Man's attempts to regulate the creative chaos. Environmental concerns got caught in the tug-of-war. Event organizers had long promoted a "leave no trace" ethic and ensured that volunteers scrub the desert of the last cigarette, but a chorus of demands for increased environmental responsibility helped motivate last year's eco-theme: Green Man.

Burning Man environmental manager Tom Price is proud of the strides made by participants and organizers and has little patience for what he considers the puritanical navel-gazing that has infiltrated the artistic free-for-all. Sporting a perpetual five o'clock shadow and the aesthetics of Indiana Jones, Price kicked back at the 2007 event in a comfy, dust-encrusted green chair perched atop the media-only observation platform.

"It's ridiculous to even consider eliminating [this type of] art from our lives," he said, surveying a sea of revelers. "I mean, should we recycle the Eiffel Tower? We don't really need the view, right?"

It was in 1997 that a Wired magazine story drew Price to the event for the first time, and he hasn't missed one since. As a college student, he waded into the University of Utah's antiapartheid struggle, winning a precedent-setting free-speech lawsuit. He spent almost a decade working with a variety of conservation groups in Washington, D.C., notably on preserving Utah wilderness, before striking out as a freelance environmental journalist. He reported on the island nation of Tuvalu's losing battle with global warming for the July/August 2003 Sierra.

"The idea of building a sustainable, temporary city in the middle of nowhere is preposterous on its face," Price said. "What we've been able to accomplish is extraordinary. Because we build the city from the ground up, we're able to change whatever we want to on a dime. We've looked at transportation, solid waste, materials, energy, art, media--everything, all aspects of the event."

Price knows the event has a long way to go. Generators still power most of the city's camps and art installations. But burners are searching for solutions, he said. Last year, for example, several camps added biodiesel from local sources to the energy mix. Organizers also took a first step toward clean and renewable energy by installing a 30-kilowatt solar photovoltaic system to power the central art pavilion that surrounds the Burning Man statue. The output didn't make up for the expenditure of fossil fuels required to truck it out to the desert, but for Price that's beside the point.

"If one person sees a solar array for the first time, understands how it works, and then goes home and installs one, then we've succeeded," he said, staring at the sprawling solar array volunteers had arranged in the shape of the Pueblo people's sacred sun symbol.

And in the spirit of the gift economy, the festival's Black Rock Solar nonprofit plans to build solar arrays that could produce 500 kilowatts of power for Nevada communities.

Elsewhere at the 2007 Burning Man, thanks to experimental-technology enthusiasts, participants could check out an algae bioreactor or admire a $98,000 all-electric Tesla Roadster (strategically covered in black cloth to adhere to the event's anti-advertising ethos).

Berkeley, California, tech artist Jim Mason's gasified art vehicle, the Mechabolic, also debuted on the desert. A green geek's dream, the Mechabolic is powered by walnut shells, coffee grounds, and the like. Burned at a high temperature with limited oxygen, the garbage becomes energy--and fertilizer. Although the Mechabolic rarely worked--Mason spent most of the week applying wrenches to its innards--participants did gather around to discuss alternatives to petroleum-based transportation.

Nearby, at Camp Hook-Up, folks who said their credentials included Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) training taught workshops on green building practices. Lance Polingyouma of the Hopi tribe said he had come to Burning Man to learn how to make his boss's Arizona resort friendlier to birds and butterflies. He was impressed with the density of expertise at Camp Hook-Up.

"The yahoo in the chicken suit is a lawyer," Polingyouma said. "The crazies running around naked are all architects."

At the centrally located Green Pavilion, art installations focused on such issues as genetically engineered corn and the impact of the enormous floating plastic garbage patch that's strangling Pacific Ocean life. For Price, the sum of all this eco-activity reflected "a fundamental expansion of awareness."

"If we want to address environmental issues," he said, "we have to get everyone involved. If the criteria are so extreme that most people won't participate, then those very few true believers will drown with their chins held high--along with the rest of us--because their perfectionism will have precluded the involvement of the mass of people we need."

Critics have it exactly wrong, Price said. The wild desert party is not Nero fiddling while Rome burns but a chance to motivate people to try out environmentally friendly ways of living. "It turns out that one of the more interesting and useful places to take action and learn is in the middle of absolute nowhere," he said.

A FEW DAYS BEFORE heading to Burning Man last summer to celebrate her 27th birthday, Zavalney--friends call her "Pinball"--sat with her laptop in the yard of her Oakland, California, home, an ecologically oriented cooperative complete

Between blasting communiques to green team members and answering frantic phone calls from burners about to pass beyond the reach of civilization and cell phones, she crafted seed balls as gifts for her compatriots to plant.

As chickens clucked in the co-op garden, Zavalney recalled that she first voyaged to the desert party in 2002. It was the year she left home for college. Seeking transformation, she hooked up with the Egyptian-themed Earth Tribe camp and painted an enormous phoenix. Then she and her brother burned it to celebrate moving into a new phase of life.

Zavalney's camp won a leave-no-trace award for its cleanup efforts. In future encampments she continued to be environmentally responsible but found herself increasingly uncomfortable.

"I was walking around feeling unhappy," she said. "Like, gosh, people think this place is so progressive, but it smells so bad from all the generators, and it's so loud."

So Zavalney, who earns her living "mapping the ecology of the sustainability movement" for a San Francisco Bay Area nonprofit, worked with several like-minded burners to convince festival organizers to shoulder more environmental responsibility. Every year, for example, most burners haul in 15 or so plastic water bottles each--hundreds of thousands total. Aside from the energy that goes into making, filling, and transporting them, most end up in landfills, leaching poisons into the groundwater, or get recycled in ways that don't reuse much of the plastic.

Taking a break from the heat at last year's festival, Zavalney drank deeply from a big jug of water while chilling in a tent with her friend and Entheon Village campmate Matthew "Hitch" McDermid. His take: Large camps should band together to truck in water, or Burning Man could centralize water distribution and build the cost into the $200-plus ticket prices. This, McDermid said, would push the event away from self-reliance to an ethos of community interdependence.

For her part, Zavalney thinks it's time for celebrations to focus people on feeding, sheltering, and clothing themselves with substances that can be produced year after year--permaculture--as opposed to big explosions.

Plenty of attendees thought Burning Man's efforts to go green were frivolous, what one termed "a colossal joke." Some of Zavalney's friends, including 12-time burner Ray Cirino, are planning to pack their ideas for Burning Man into a new festival.

"Instead of building a city and tearing it down or destroying it, we're going to keep the city and build a cultural and learning center," said Cirino. "I'm hoping to hold the event at a depressed property that needs help, preferably on indigenous land, and resuscitate a watershed. We'll be building a food forest as well."

The new festival will feature unplugged music, encourage children and families to attend, and discourage drug use. Cirino says he hopes to hold the festival in California sometime in spring 2009.

Zavalney can't wait. "Let's build systems where people get together and renew and restore our dying planet, rather than burn things to prove a point," she said. She's particularly fond of the event's name: Water Woman.

AS GREEN MAN DREW TO A CLOSE and thousands of idling, carbon-emitting cars lined up for miles and hours on the sole one-lane road back to the rest of the world, a curious drama unfolded in a forgotten corner of a partially dismantled Black Rock City. On the back of a big truck, a dozen yards from the charred wreckage of the Crude Awakening oil derrick, a 50-foot-tall nursery-grown, potted, living redwood tree waited to make a surprise grand entrance. It was not to be.

The Crude Awakening artists had intended to raise the tree in place of the incinerated oil derrick as the object being prayed to by the reverent metallic figures. It would have symbolized humanity's turn toward nature after the fossil-fuel crash. But Burning Man organizers, worried about needle litter, asked Bureau of Land Management officials to enforce the festival's no-plants policy (most vegetation dies in the desert) and ban the tree. So the largest living organism to visit the desert in 10,000 years never made it off the truck bed.

Ethics and Indulgences

For 2007 Burning Man participants who felt guilty about how they've been treating the planet, a "priest" from the Dominican University of California set up an eco-confessional booth.

"If, in your heart, you feel like you're doing the right thing," the confessor cooed, "then you have not been eco-sinning."

That's not the position I took at the festival's carbon-offset debate, at which I opposed the idea that people and companies can make up for the fossil fuels they burn by giving money to someone who'll do something to cut an equal amount of greenhouse-gas emissions elsewhere.

David Shearer, a Toyota Prius designer and the brains behind Burning Man's carbon-offset plan, defended the practice. If everyone attending the festival invested in about one ton of carbon offsets--average cost $12--for wind turbines or methane-gas electricity generators, he said, "we'd be the first carbon-neutral city on the planet."

I advocated for environmental journalist George Monbiot's indictment of carbon offsets as the modern-day equivalent of medieval priests selling indulgences.

"By selling us a clean conscience, the offset companies are ... telling us that we don't need to be citizens; we need only be better consumers," Monbiot wrote in the Guardian newspaper. His point: To achieve the overwhelmingly large cuts in greenhouse gases necessary to prevent global warming from crossing the apocalypse threshold, we must build wind turbines and stop flying. "Thinking like ethical people," Monbiot says, "makes not a damn of difference unless we also behave like ethical people."

The debate concluded prematurely when a dust storm roared through, scattering the audience in a strong but ambiguous sign from above.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club