How to Make Home a Haven

Here are easy steps for making your domicile a home for birds, bats, and bees

Illustrations By Jess Lyon

Birds, bats, and pollinators need our help—their numbers are falling by the billions as habitat loss threatens global biodiversity. While the problem is systemic, each of us can lend a hand by making our own spaces a bit more creature-friendly. Doug Tallamy, cofounder of the conservation project Homegrown National Park, argues that since a vast number of US land parcels are residential, it's time to reenvision such spaces as potential wildlife refuges. "That's 135 million acres," he says, "ripe for us to landscape in a way that allows us to live with nature instead of being segregated from it."

Whether people are greening up apartment patios or making suburban yards wildlife-friendly, nature's DIY brigade is growing.

The idea of small-scale rewilding is catching on. More than 22,000 households have signed on to Homegrown National Park's mission to foster biodiversity at home. And the National Wildlife Federation reports that the number of people planning to transform a portion of their lawn to native wildflower landscape doubled from 9 percent in 2019 to 19 percent in 2021.

Whether people are greening up apartment patios or making suburban yards wildlife-friendly, nature's DIY brigade is growing. Here's how to join in—wildflowers and beyond.

Go Native

Tallamy puts it succinctly: "Plant the right plants and nature will come." Local wildlife populations have coevolved with their region's native flora. If you get rid of the plants that animals depend on, the entire ecosystem can fall out of whack. By laying concrete patios, seeding lawns, and planting common exotic trees and shrubs, we've created food deserts for our backyard creatures. Going native replaces what we took.

How you go native, of course, depends on where you live. Both Audubon and the National Wildlife Federation have handy native-plant finders based on zip codes. Wild Ones collates recommended nurseries and offers free, professionally designed native-garden templates for many US regions. On the ground, talk to your local nursery about what native plants it carries—be sure to ask for straight natives, not nativars, which may carry attributes that make them less valuable to wildlife, like nutritionally deficient color and altered blooming times.

Native trees bundle long-lasting wildlife habitat with a host of other benefits, making these a high-impact choice in many US locales. Oaks are rewilding superstars, Tallamy says. The trees are wildlife favorites that also sequester carbon, feed pollinators, and support healthy watersheds.

Take It Further Than No Mow May

The movement to stow away our lawn mowers in spring, No Mow May, has jump-started a sense of duty to pollinators and wildlife that luxuriate in untrimmed yards. But its messaging can oversimplify the solution. "Wildlife need a diverse plant palette," Mary Phillips, head of the National Wildlife Federation's Garden for Wildlife, explains. "Unfortunately, lawns left to grow that only have one flowering species, or non-native grasses, limit essential habitat benefits."

You don't need to be a lawn-less renegade to make positive change. As landscape architect Thomas Rainer notes, lawn should be an area rug, not "wall-to-wall carpeting." A bit of lawn has a purpose for kids and pups; a big lawn takes away from the environment and can be a serious water hog. For low-growing, walkable areas akin to lawn, look into native ground cover options like wild ginger. And if you're in an especially drought-prone area, know that native plants are integral to xeriscaping, which usually doesn't require watering beyond the first year.

As your lawn goes from naked to native, it might raise eyebrows. Beyond directly filling people in on your plans—and extolling the benefits of natural landscaping—the National Wildlife Federation recommends adding "human touches" to your space, like birdbaths, benches, and ornaments. Explanatory signage, like pollinator-habitat signposts from the Xerces Society, can spark conversations.

Don't Write Off Small Spaces

Rewilding works even if you're limited to a teensy apartment patio. Tallamy points to fall aster, milkweed, and joe-pye weed as natives that do well in containers, though the list goes on. If the spaces are accessible to the outdoors, Tallamy says, "the mobile things that require those plants will take advantage."

Just have a windowsill or a patch of grass around a mailbox? Those matter too. There are many ways to start simply, from a packet of native seeds at your local nursery to the DIY small-space native starter garden collections the National Wildlife Federation offers. Your garden, no matter the size, could become a new wildlife stopover.

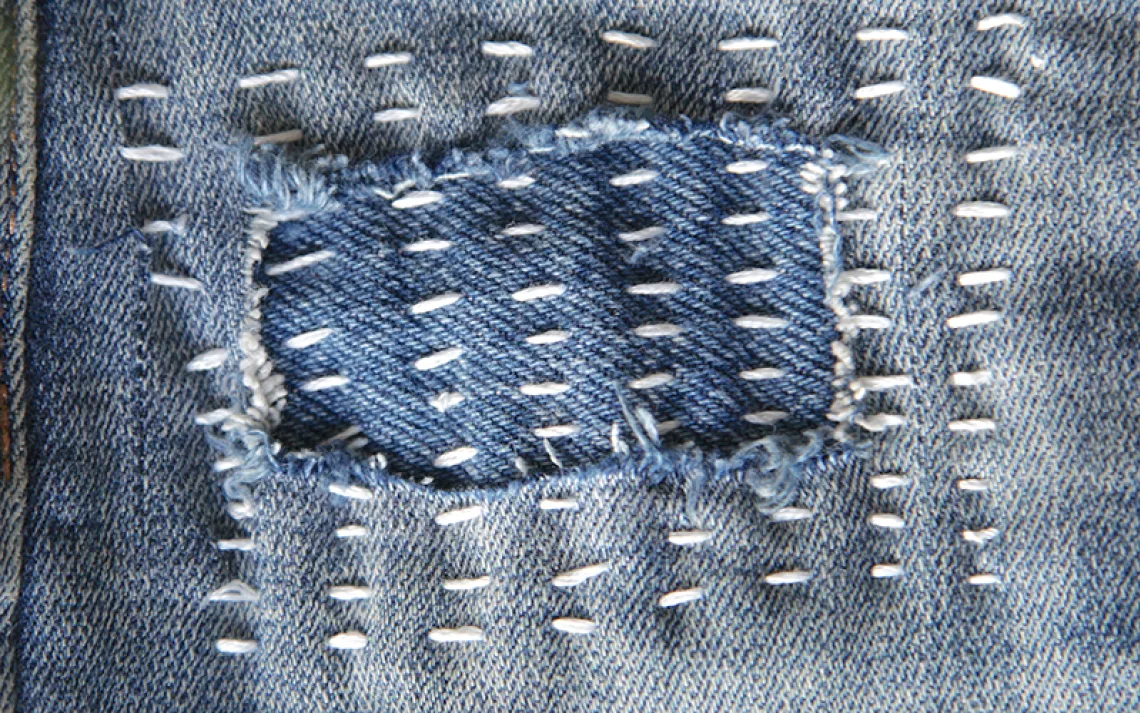

Put Up Nesting Boxes and Bat Houses

One of the key aspects of a wildlife habitat is shelter—cavity nesters, such as chickadees, need a safe space to build their nests while dodging predators and the elements. Nesting boxes can also attract various bird species that may not come to your feeders but are searching for a dwelling place.

The same idea extends to bat houses. Female bats need safe places to raise their young. When you provide them with a home, bats will eat mosquitoes, moths, and beetles in your yard and will be less likely to set up shop in your attic. If you aren't sure about welcoming bats, know that they usually only give birth to one pup a year. And the brush pile you've been meaning to get around to? Plenty of animals don't use cavities, so that brush is likely a fixture for creatures including sparrows, warblers, and bugs. Leave it be.

Provide Food and Water for Birds

"Feeders and birdbaths can support and attract birds throughout the year," says Geoff LeBaron, Christmas Bird Count director for the National Audubon Society. In winter especially, put out high-nutrition foods like suet, peanuts, and black-oil sunflower seeds.

There's one catch: Feeders and birdbaths must be properly maintained. Seed and suet feeders should be cleaned at least every other week, and more frequently in humid or hot weather. Hummingbird feeders should be cleaned every few days, or whenever the sugar solution becomes cloudy. Birdbaths should be cleaned weekly, and the water replaced every other day. They don't need to be fancy; even a plant saucer can do the trick, filled with an inch of water and a few large pebbles (stones help birds gauge water depth before stepping in). Placement of feeders and baths is key. They should be near—but not too close to—shrubs or trees that can provide cover if birds feel threatened, LeBaron explains.

Note: With the spread of avian flu, you should keep tabs on whether your local, state, or federal wildlife agencies recommend removing wild-bird feeders. "If at least one of your local agencies advises they be removed," LeBaron says, "we recommend following those guidelines."

Bird-Proof Your Home

While it's impossible to get exact numbers, it's estimated that up to a billion birds die each year from window collisions. Products such as decals, window film, cords, netting, and screens help prevent this. You can also use DIY, nonpermanent tempera paint or soap on windows to make the glass more visible to birds. Moving large houseplants away from windows is another useful precaution, and placing bird feeders directly on windows—or within three feet of them—can minimize window collisions too.

Turn Out Your Lights at Night

Light pollution adversely affects nearly every living creature, including us. From altered migration patterns to disoriented communication to hastened reproduction, the ramifications of our well-lit world are felt by all classes of animals—birds, insects, and mammals. If you can’t go dark, invest in warm, shielded LED lighting (under 3,000 kelvins) and install motion sensors.

Keep Cats Indoors

Cats are one of the top human-related causes of bird deaths, ranking right up there with window collisions and habitat destruction. We're talking billions of cat-caused bird fatalities every year, and that's not including the other creatures that run across a cat's path. Keep yours indoors to avoid adding to the carnage. In addition to being safer for your backyard wildlife, it's safer for your feline too.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club