Walnut Creek Wetland Park provides case study on environmental justice & faith-based community organizing

By Austin Spence

North Carolina is home to a rich history of environmental organizing efforts to protect lands and people. Lauded as the birthplace of the environmental justice movement, the state is home to a variety of natural terrain as well as human communities. It's no small feat to protect and advocate for both.

As a five-year resident of Raleigh, I've established a routine of exercising around the city via the greenway system. One place I visit is the Walnut Creek Greenway, a path that runs along the city's south side toward the Neuse River.

In the past, I never slowed down enough to take in much of the Greenway's natural surroundings. Since I partnered with the Sierra Club for the summer, that's changed.

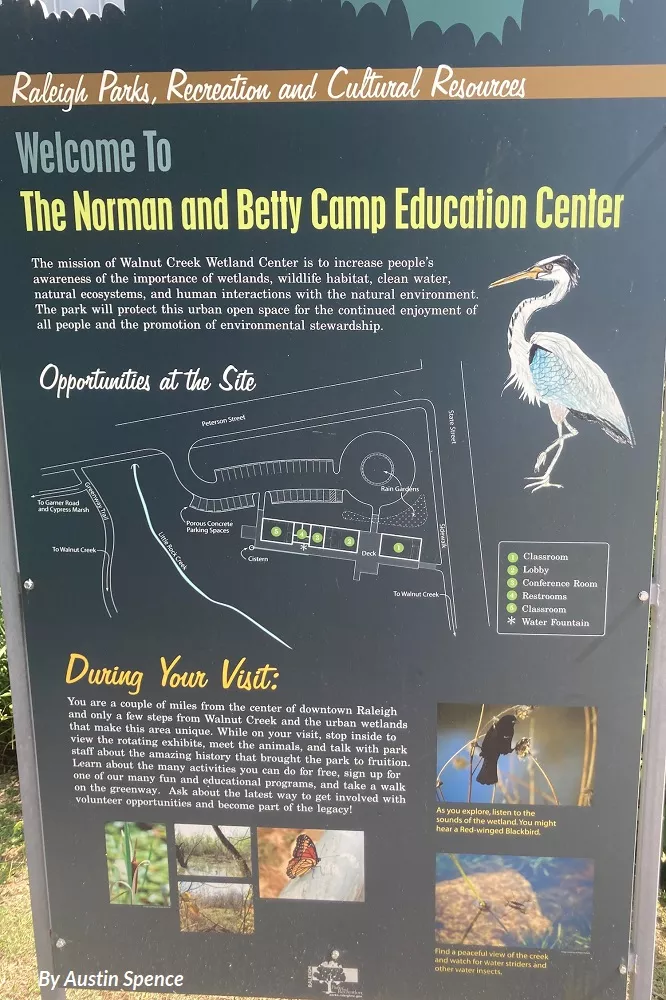

Within one week of beginning to research wetlands policy, my eye for these natural areas has become more developed. Turns out, there are plenty of wetlands around Raleigh. One of the more notable is the Walnut Creek Wetland Park, on the southeastern edge of downtown. The city-run park includes a nature center for information and event space, walking trails, picnic tables, and much more.

As I've become familiar with the site, it's obvious that its value exceeds the services the city offers at the park. While it's a great place to connect people in urban areas with nature, it also offers a lens into the history of the area and a poignant look at environmental justice within Raleigh's borders.

As told in this May 1, 2019, story in Walter Magazine, one of the first planned subdivisions for Black families in Raleigh was on floodlands south of the wetland area: Rochester Heights.

As a natural flood-mitigating structure, the wetland would help store excess water from storms. But as newer upstream developments increasingly displaced water and the wetland was used for trash dumping, homes were flooded, sometimes completely washed off their foundations. As time passed, the city dumped sewage into the wetland as well.

Luckily, the wetland is home to a community of people who are adept at identifying problems and working together to fix them. Members of St. Ambrose Episcopal Church were fed up with the displaced water in surrounding areas of the wetland due to waste disposal. All it took was one parishioner to raise concern for the church to begin clean-up efforts in the 1990s.

As the Walter Magazine story recounts, more and more community members joined in. With the newfound pride in the area, the goal transitioned from cleaning up the wetland to preserving it, keeping it healthy, and celebrating it as a unique feature – a healthy natural area close to an urban center.

More churches joined the effort, formally organizing as “Partners for Environmental Justice.” They applied for and received grants to make large-scale changes to the wetland, promote better flood mitigation, protect the surrounding housing structures, as well as establish a nature center to connect people to the area. Surveyors went around the neighborhoods to understand the priorities that community members hold for the area as well as hear about the extent of the flooding impacts on living conditions. Ultimately, city leaders got on board, and the wetlands center was opened in 2009.

While wetlands dumping is a quick fix for getting rid of trash, in the long run it destroys habitat and harms human inhabitants by undermining the land's natural ability to slow flooding and filter our groundwater. When impacted communities turn to collective pushback and advocacy, we must join their fight.

Environmental justice advocates must be enmeshed in the knowledge of natural environments as well as in the community they hope to serve. Faith communities are improving their efforts to extend care beyond the confines of religious spaces and into the world. This includes identifying opportunities to care for the environment (e.g. creation care), which serves the people they interact with consistently.

Environmental justice has come a long way from its beginnings in Warren County. Still, there's plenty of work to do federally and within the state. While the Supreme Court's Sackett ruling undermined protection for many wetlands, the door is open for individual states to fill that void. Early this year, Gov. Roy Cooper signed Executive Order 305, a necessary step for the state to protect its nearly 5 million acres of wetlands, as well as other natural lands. Adopting the spirit of the St. Ambrose congregation can be a catalyst for statewide action.

North Carolina is fertile ground for environmental justice movements, given the variety of natural features and variety of urban, rural, mountainous, coastal, racial, and tribal communities. The movement calls city planners, politicians, engineers, and more to consider the impacts of the built environments they help to create and maintain.

Environmental justice asks the question: “Does this space encourage a life of flourishing? Will certain actions degrade the environment which negatively affect the lives within and surrounding the area?” The only acceptable answers to such questions will value the people and the places for generations to come.

—

Austin Spence is one of the Chapter's 2024 Environmental Conservation and Justice Policy Fellows. He is a graduate student at Duke University, working toward Master of Public Policy and Master of Divinity degrees, with a certificate in faith, food, and environmental justice.