By Dillon McLaughlin

By Dillon McLaughlin

Let's start with some technical jargon. When we say PFAS chemicals, we're referring to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. But that's unapproachably technical for the layperson and even the writer of this article can't confidently say that out loud. Really, I’ve just copied it from Washington State's Department of Ecology. So in the same way we don't call DDT Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, let's agree that we're just going to say PFAS from now on.

As foreign and technical as they sound, they're everywhere. That Washington State link has a good list of products containing PFAS, and it's eye-popping. It includes upholstery, nonstick cookware, any waterproof clothing, cleaners, waterproof and grease-resistant food packaging, and equipment for food processing. They’re also extremely common in Class B firefighting foam and come with federal mandates about their use during emergencies and training exercises. Between all of their uses, it's almost a guarantee you touched PFAS today. Or that you're currently wearing them.

For similar chemical crises, like DDT, PCB, and mercury pollution, the solution was to simply isolate the places where the chemicals were deposited and clean those areas. When there were high levels of dangerous chemicals in the Hudson River, all they had to do was gather contaminated sediment, do whatever science magic they did to clean it, then stick it back where it was. There was some damage done by pollution, sure, but it wasn't anything we couldn't make right.

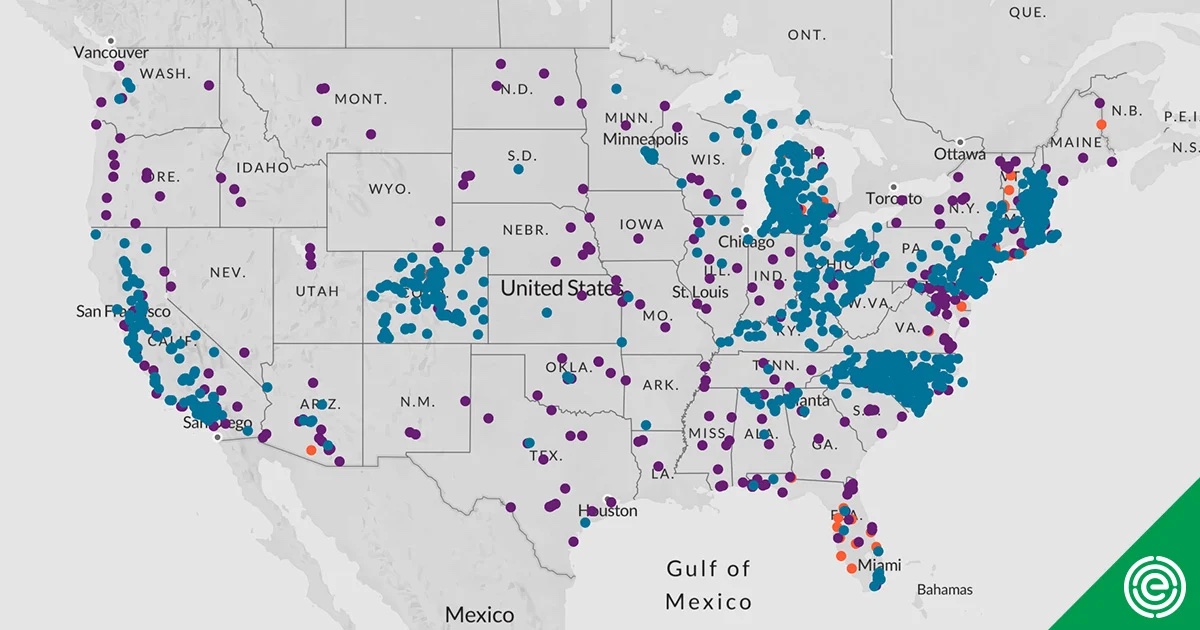

With PFAS, that's not really possible. They're water soluble, so as soon as they touch water, they disperse and can't be isolated. Once they’re out there, they’re out there and spreading everywhere fast. At least 43 states have some level of PFAS contamination in their water supply, directly affecting some 19 million people. Water solubility means they're virtually ubiquitous.

To compound the problem, they're “forever chemicals.” That means they're potentially never going to break down, and if they do break down, it'll be over hundreds or thousands of years. That'd be like if the Romans drilled for oil in the Mediterranean and had a Deepwater Horizon-level catastrophe, and we were still cleaning up the spill.

These chemicals contaminate the household products you use and pollute the water you drink and the food you eat, since the food you eat also consumes water. All of this comes together to mean nearly 100 percent of Americans have PFAS in their blood. What's worse is that they're notoriously hard to study, and deeper dives into their health effects have only really just started. So far, they’ve been tied to various types of cancers, especially in the kidneys and testicles, as well as damage to liver enzymes, increased cholesterol levels, damage to infant health, and depressed vaccine efficacy in children (that last one is a bear we really shouldn't be poking right now).

Delaware hasn’t been spared any of this. PFAS were first found in the groundwater in Dover back in 2014 at levels well above the EPA's lifetime health advisory of 70 parts per trillion. Since then PFAS have been found in New Castle County and in Blades in Sussex County, not to mention all the military bases, airports, and industrial parks across the state.

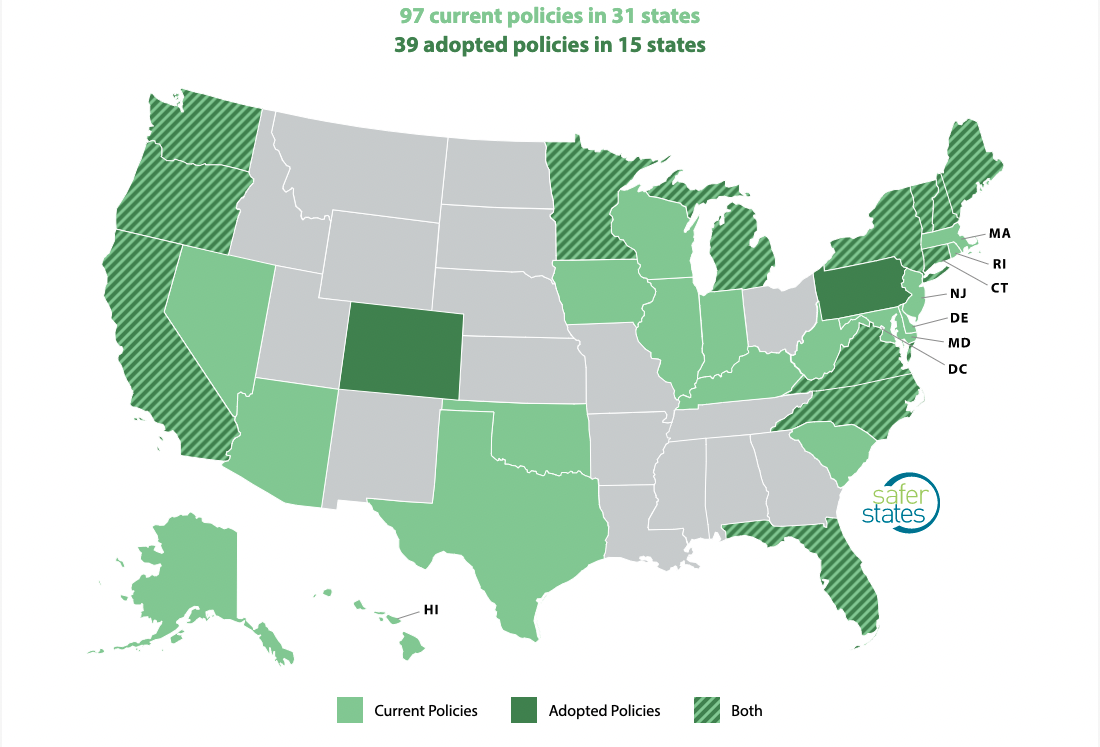

The only real solution lies somewhere in the vicinity of a full ban on their use. Or at least severe restrictions and close monitoring to minimize spread. The good news is that's well within the realm of possibility, and there are a couple of Delaware politicians who are working hard to write a bill that actually protects the public. Senators Marie Pinkney and Stephanie Hansen come to mind. We'd love to have more lawmakers on board, too.

But, as usual, just when it looks like environmentalists are on the cusp of making life better, safer, and healthier for everyone, which we certainly are with PFAS, corporate lobbyists start whining about their clients' profits and business interests, then they shove themselves into the situation by proposing their own handcrafted bills. These are bills that sound good in their abstract but don't actually address the core concerns of environmentalists and the general public.

Case in point is SB63. It was written and proposed by the Alliance for Telomere Chemistry Stewardship, and the director of the American Chemical Council Inc., Shawn Swearingen, made a big push for the bill at the Senate Corrections and Public Safety Committee meeting back in March.

It ostensibly addressed PFAS concerns, with nice language about how important it is to identify and contain the chemical before it can get into the water supply (which it already has). Since it sounded like it was in the public's interest, a bunch of state legislators jumped on board as sponsors. But a closer look at the language reveals it was really a continuation of the chemical industry's standard legislative practice, and once that became clear numerous legislators removed their name from the legislation.

For example, a handful of Whereas clauses in SB63 talk about the lack of effective alternatives to PFAS in reference to firefighting foam, which isn't true, and the bill goes on to establish liability exemptions for manufacturers who get caught contaminating the water supply. It essentially legalizes what the chemical companies are already doing, while also admitting that what the chemical companies are doing is damaging the environment and people's health.

Imagine if an arsonist proposed a bill that said setting houses on fire was dangerous and bad and should obviously be made illegal. But what the bill actually did was declare that this particular arsonist should never be impeded in his ability to set fires, there was regrettably no alternative to setting houses on fire, and he can't be prosecuted for the houses he has set on fire, is currently setting on fire, or will soon set on fire. It might sound like a hyperbolic argument, but that's what happens when corporations and their lobbyists are allowed to write the legislation that's meant to regulate their industries.

It should be said that as soon as state senators realized what the bill actually did, more and more of them had their names removed from the bill, and it was ultimately pulled from the agenda of the meeting scheduled for Wednesday, April 21st.

Opponents of a PFAS ban usually say a total ban is economically infeasible. That's the kind of statement that sounds like it might be true but doesn't actually hold up to reality, like when business moguls claimed outlawing child labor would crater our economic competitiveness or when pseudo-scientists said a heavier-than-air flying machine was impossible. The truth is other states have banned PFAS products and are doing just fine. California banned them last year, with a total halt on sales to take effect in 2022. California would also be the fifth largest economy in the world if it were counted as its own separate country, falling between Germany and the UK. Germany, by the way, is part of the EU, which has imposed severe restrictions on PFAS usage. The state of Washington has also banned PFAS in food packaging. Private companies are even jumping on board, with Lowe's and Home Depot phasing out carpets and rugs that contain PFAS chemicals.

You'll notice California, Washington, and the EU haven't suffered catastrophic economic damage, and Lowe's and Home Depot haven't imploded as a result of their restrictions. The main result of the bans have been companies supplying substitute products that don't have PFAS chemicals in them. Californians can still buy raincoats, Germans can still buy cookware, and Washingtonians are presumably still eating food. Lowe's and Home Depot definitely still carry rugs.

If Delaware jumped on that bandwagon, the way Maryland and Arkansas have, it would mean little to no disruption for Delawareans and a minor inconvenience at worst for retailers. We'd be getting the products they were already planning on selling in California and that we'd be buying at Lowe's and Home Depot anyway, but with the added benefit of not having to drink PFAS every time we turned on our home tap.