Climate change threatens nearly half the bird species in the continental U.S. and Canada, including the Bald Eagle and dozens of iconic birds like the Common Loon, Baltimore Oriole and Brown Pelican, according to a new study published by National Audubon Society.

The handsome and colorful Baltimore Oriole is seen as birdfeeders across New York. Photo Credit: David Disher, courtsey of Cornell Lab of Ornithology |

The study identifies 126 species that will lose more than 50 percent of their current ranges—in some cases up to 100 percent—by 2050, with no possibility of moving elsewhere if global warming continues on its current trajectory.

A further 188 species face more than 50 percent range loss by 2080 but may be able to make up some of this loss if they are able to colonize new areas. These 14 species include many not previously considered at risk. The report indicates that numerous extinctions are likely if global temperature increases are not stopped.

“It’s a punch in the gut. The greatest threat our birds face today is global warming,” said Audubon chief scientist Gary Langham, who led the investigation. “That’s our unequivocal conclusion after seven years of painstakingly careful and thorough research. Global warming threatens the basic fabric of life on which birds—and the rest of us—depend, and we have to act quickly and decisively if we are going to avoid catastrophe for them and for us.”

“The prospect of such staggering loss is horrific, but we can build a bridge to the future for America’s birds,” said David Yarnold, Audubon president and CEO. “This report is a roadmap, and it’s telling us two big things: We have to preserve and protect the places birds live, and we have to work together to reduce the severity of global warming.”

Langham and other Audubon ornithologists analyzed 30 years of North American climate data and tens of thousands of historical bird observations from the Audubon Christmas Bird Count and U.S. Geological Survey’s North American Breeding Bird Survey to understand the links between where birds live and the climatic conditions that support them. Understanding those links allows scientists to project where birds are likely to be able to survive—and not survive—in the future.

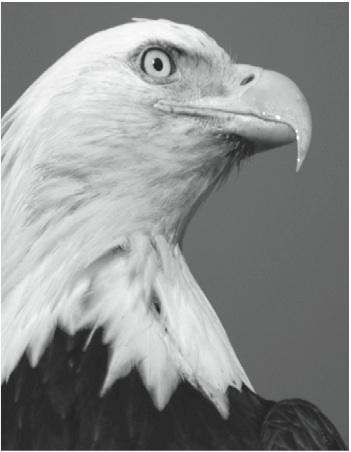

The Bald Eagle, national symbol of the U.S. could lose 75 percent of its summer habitat. |

While some species will be able to adapt to shifting climates, many of North America’s most familiar and iconic species will not. The national symbol of the U.S., the Bald Eagle, could see its current summer range decrease by nearly 75 percent in the next 65 years. The Common Loon, icon of the north and state bird of Minnesota, may no longer be able to breed in the lower 48 states by 2080.

The Baltimore Oriole, state bird of Maryland and mascot for Baltimore’s baseball team, may no longer nest in the Mid-Atlantic, shifting north instead to follow the climatic conditions it requires.

Other state birds at risk include Brown Pelican (Louisiana), California Gull (Utah), Hermit Thrush (Vermont), Mountain Bluebird (Idaho and Nevada), Ruffed Grouse (Pennsylvania), Purple Finch (New Hampshire) and Wood Thrush (Washington, D.C.).

“We know that climate variables—including temperature and precipitation—determine where most birds live and where they don’t, because it is too hot, for example,” said Terry Root, a Nobel Prize-winning Stanford University professor who serves on Audubon’s board of directors but was not involved in the study.

“The Audubon study determined the climate variables that dictate where all North American birds live today and then brilliantly used climate forecasts to project where birds will most likely occur in the future. We all will see the effects of changing climate in our own backyards. We just cannot ignore such a sobering wake-up call.”

The study, which was funded in part by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, has numerous implications for conservation, public policy and further research and provides a new suite of tools for scientists, conservationists, land managers and policy makers. For example, the study identifies “strongholds,” areas that will remain stable for some birds even as climate changes and are candidates for protection and management.

The Common Loon is the iconic bird of the Adirondack lakes. Photo Credit: Steve Maslowski, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

Audubon has launched a new web portal—Audubon.org/Climate—dedicated to understanding the links between birds and global warming, including animated maps and photographs of the 314 species at risk, a technical report, and in-depth stories from the September-October issue of Audubon magazine, which is also devoted to the topic.

“Millions of people across the country will take this threat personally because birds matter to them,” said Yarnold. “For bird lovers, this issue transcends nasty political posturing; it’s a bird issue. And we know that when we do the right things for birds, we do the right things for people, too.

“Everyone can do something, from changing the plants in their backyard to working at the community and state level to protect the places birds will need to survive and promote clean energy. We are what hope looks like to a bird.”