By Linda Pauer

“Wildlife crossing structures have been shown to be one of the most effective means of reducing animal-vehicle collisions on highways, while facilitating essential animal movement across the landscape. Yet the widespread implementation of such structures, especially wildlife overpasses, has been hindered by their perceived and actual expense,” according to a March 2021 publication from the Forest Service. I think the homework has been done. But how do crossings get funded?

In November of 2023, the NFWF (National Fish and Wildlife Foundation) announced $141.3 million in grants through the America the Beautiful Challenge (ATBC), for “high-priority conservation projects across the US to support projects that conserve, restore and connect habitats for wildlife while improving community resilience and access to nature.”

The smallest of those grants, $250,000, will go to repurposing the Osburn overpass in Idaho to serve wildlife, funneling large mammals away from the roadway and connecting the Coeur d’Alene and St. Joe National Forests. This project takes an abandoned structure of concrete and asphalt – an overpass that reportedly no vehicle has crossed since it was built in 1969 – to mitigate the roadkill along HWY I-90. Applause goes to enthusiasts and locals who took it upon themselves to leverage the existing bridge, where building from “scratch” would cost more than $6 million.

In December of last year, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) $110 million in grants for 19 wildlife crossing projects in 17 states, including four Indian Tribal Lands. The funding was made possible by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and can support projects that construct wildlife crossings over and under busy roads, add fencing, acquire tracking and mapping tools, and more. Overall, BIL makes a total of $350 million available over five years under the Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program. They report that, “the California Department of Transportation will receive $8 million to reduce wildlife vehicle collisions and connect animal habitats between protected State Park lands on either side of US 101. Improvements include increasing the size of an existing culvert and installing 2.5 miles of fencing at road crossings, allowing for safer roads for drivers.”

This is good news for California critters whose ecosystems have been sliced by highway expansion such that death is the risk in finding mates or meals. According to the UC Davis Road Ecology Center, there were more than 44,000 wildlife-vehicle collisions reported in California from 2016 to 2020, resulting in injuries and deaths to drivers and wildlife.

The notion of a wildland bridge is not new. In France the simple concept of saving the lives of badgers, elk and other mammals inspired some of the first efforts in the 1950s. The idea was quickly adopted in the Netherlands, where cars are fewer because mass transportation is easily accessible to the local population of about 18 million human inhabitants, and more than 600 crossings have been constructed to date. Here in California, where more than 39 million people live and drive, one might expect at least 1200 crossings or more given the relatively infrequent use of public transportation. I’ve said it before: let’s look to where others have successfully mitigated the high cost of roadkill.

The NCSL (updated September 2022) reports that “several states have enacted legislation in recent years to identify and protect wildlife corridors, contributing to over 1,000 dedicated wildlife crossings in the U.S. today.” We have a long way to go!

Identifying barriers to wildlife movement and prioritizing crossings when designing roads can include overpasses, underpasses, culverts and more, to mitigate collisions with wildlife. Although $1 billion in new funding became available here in California, these funds are from the general fund and their continued availability for this intended purpose is at risk.

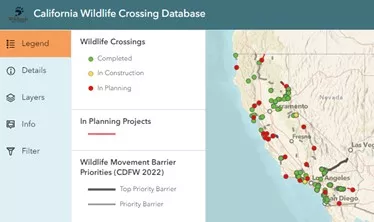

In California the Wildlands Network publishes a comprehensive map showing both completed and ongoing wildlife crossing locations to date. Curious about local projects? You can find details on each structure, including its project status, year built, crossing type (e.g. bridge, underpass, culvert, etc.) and supporting documentation, when available. Also, see highlighted road segments that identify California Department of Fish & Wildlife’s priority barriers to wildlife movement. Are we close to 1200 bridges and corridors here in California? Not yet!

Let’s get going! In collaboration with CalTrans, UC Davis and CDFW, the Alameda County Resource Conservation District (ACRCD) began work in October 2023 on 3 crossings. A $7,094,000 grant from the State Wildlife Conservation Board will support the first phase of the project. With persistence and luck, our critters will have crossings in 10 years, according to Katherine Boxer, ACRCD chief executive officer. Until then, our pumas, mule deer, coyotes, black bears, bobcats, bighorn sheep, wolves, porcupines, and many more are struggling to survive.

Next issue: What is the Sierra Club doing in support of wildlife crossings?