Who's to Blame for Climate Change?

New research builds evidence against a handful of culprits

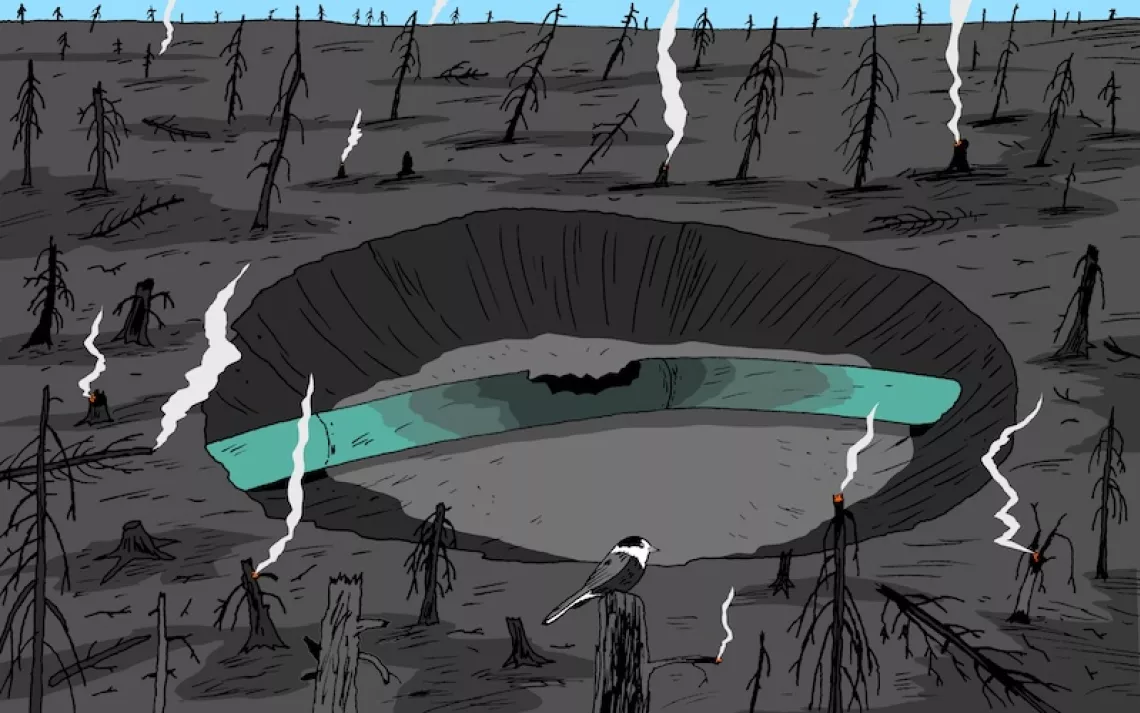

Photo by iStock | Igor Kozeev

My grandmother was shy. She liked how when she held a cigarette, the smoke hung like a veil between herself and the rest of the world. Even after she realized how dangerous smoking was, she didn’t manage to quit until a few months before she died of cancer.

At the time when she was trying to stop smoking, people like her were seen as flawed—lacking in some form of willpower that would allow them to step off a path that clearly led to self-destruction. But in the decades after she died, the story changed. The problem wasn’t that two out of every five Americans had a toxic lack of self-control. The problem was that the companies that sold the cigarettes baldly lied about how dangerous they were and modified their product over a period of decades to be even more addictive. A villain had emerged, like a statue slowly being chiseled out of a block of granite.

Over the years that I’ve written about climate change, I’ve seen a similar shift in perspective. In the early days, I encountered sanctimonious exhortations to fight climate change in ways that were both awesome and of dubious global effect. Was I really saving the planet by owning a bike instead of a car? Was the single-mom neighbor who couldn’t get her kid to school, or herself to work, without driving really destroying it? Despondent “We have met the enemy, and he is us,” wallowing about humanity as a cancer on the planet was also a regular feature, though, again, it was hard to see what next steps would look like, unless you were planning on going full Magneto and declaring war on Homo sapiens.

A new study published last week in the scientific journal Climatic Change is an example of how attitudes toward climate change keep evolving. The title, The rise in global atmospheric CO2, surface temperature, and sea level from emissions traced to major carbon producers, doesn’t exactly soar, but trust me, this is basically Murder on the Orient Express, climate whodunit edition.

The paper builds on earlier work, published in the same journal three years earlier but put together by a different group of researchers led by carbon wonk Richard Heede. That paper, Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854–2010, found that two-thirds of the carbon released into the troposphere by human activity since the industrial revolution could be traced back to 90 companies and government-run industries (83 producers of coal, oil, and natural gas and seven cement manufacturers). Those companies that dug carbon-based forms of energy out of the ground sometimes burned it themselves, but mostly sold it to people who expressly intended to combust it. Heede was careful to separate out carbon-based fuel that was extracted for use as lubricants, petrochemicals, road oil, and other “non-energy, non-combustion” uses.

This new paper, whose lead author is Brenda Ekwurzel, a climatologist with the Union of Concerned Scientists, examines the actual climate effects caused by each of these companies. After factoring out other carbon sources, the paper concludes that those 90 carbon producers alone were responsible for a 0.4°C increase in global mean surface temperature (GMST), or about half of the total increased temperature in the 130 years between 1880 and 2010.

By these calculations, Heede’s 90 carbon producers contributed to 57 percent of the observed rise in atmospheric CO2, 42 to 50 percent of the rise in global mean surface temperature (GMST), and 26 to 32 percent of global sea level (GSL) rise over the last 130 years (the variation has to do with the difficulty of factoring aerosols into the numbers). Just seven investor-owned and seven state-owned carbon producers were consistently among the top 20.

About two-thirds of this warming is the result of carbon released after 1979, the year that the U.S. National Research Council published Carbon dioxide and climate: a scientific assessment. That report contained information that wouldn’t be widely known to the general public for decades, but would have been inescapable to anyone whose financial bottom line depended on putting more carbon into the atmosphere. Even a reader who only read the forward of that report couldn’t miss statements like, “If carbon dioxide continues to increase, the study group finds no reason to doubt that climate changes will result. . . . A wait-and-see policy may mean waiting until it is too late.”

Papers like those by Heede and Ekwurzel examine who was in control of the carbon—a.k.a. “the weapon,” to continue the detective metaphors. The other piece of the case, though, is intent. Were ExxonMobil, BP, Total, Shell, and the other companies that helped pull the trigger on the climate acting with the same naiveté that a toddler has when it reaches under a sofa and pulls out a gun? Or did they know exactly what they were doing in the 1980s and possibly even earlier?

Just this week, New York's highest court declared that PricewaterhouseCoopers, auditor for ExxonMobil, one of the top carbon producers in world history, had no right to refuse to release documents about its advice to ExxonMobil about the risks posed by climate change. As more information comes to light about what major emitters knew, when they knew it, and what they chose to do with that knowledge, these companies could find themselves in the same boat as big tobacco—heavily regulated, with their trade associations dissolved and many forms of advertising banned. Like tobacco companies, they could be forced by the courts to pay billions of dollars in settlements, money that could then be used to subsidize public education about the dangers of their own products.

The authors of last week’s paper seem aware of this possibility. “Size of contribution, such as calculated in this study, is one factor to consider in assessing responsibility for climate change consequences associated with atmospheric CO2 and CH4,” the paper reads, almost gloatingly. “Other factors include consideration of differences among carbon producers in how they responded to the scientific evidence of the climate risks of their products. These factors coupled with ethical, legal, and historical considerations may further inform discussions about carbon producer responsibilities to contribute to limiting climate change through investment in mitigation, support for adaptation, and compensation for climate damages.”

Despite all the political volatility associated with the oil business, the prime movers in the industry haven’t changed much at all. According to Heede and Ekwurtzel’s research, the four biggest contributors to atmospheric carbon dioxide in the last 130 years are Saudi Aramco, Chevron, ExxonMobil, and BP. The four biggest contributors since the 1980s have been Saudi Aramco, Gazprom, ExxonMobil, and the National Iranian Oil Company. These are all big names and important players. In a few years, they could be as infamous as they are famous.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club