Sanctuary Birds

Stunning portraits of the characters at the Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary

Photographs by Bob Croslin

"They're like people. Each species of bird has a different characteristic, different personality," photographer Bob Croslin says about the inhabitants of Florida's Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary, where he spent four months creating avian portraits. The sanctuary rehabilitates wild birds and then releases them—unless a bird's injuries would render it unable to survive in the wild, in which case the animal becomes a resident education ambassador. According to the sanctuary, more than 90 percent of the birds admitted have sustained injuries that can be directly or indirectly attributed to humans. By amassing this stunning collection of photos, Croslin hopes to help raise awareness about the birds and increase the visibility of the organization that cares for these unfortunate creatures. Let's meet some of the birds.

Cedar Waxwing

The elegant cedar waxwing, which makes a high-pitched see! call, appears drab from afar, but a closer inspection unveils exquisite detail. The "waxwing" in its name refers to the waxlike red droplets on the tips of its secondary feathers, and it also sports a jaunty feathered crest and a mysterious black mask. These starling-size birds feed on berries or sally off a branch in looping flight to capture insects in the air.

White Pelican

This regal white bird with a single wing couldn't survive in the wild and instead lives at the sanctuary and is brought into schools to educate students. White pelicans are one of the largest birds in North America and—unlike their counterparts, the brown pelican—don't dive for their food but rather sit as a group in the shallows and round up fish into easily captured formation. The hornlike projection on top of its long orange bill becomes apparent during breeding season and is thought to be ornamentation to help in mate selection.

American Crow

When asked who he thought was the sanctuary's biggest character, Croslin doesn't hesitate: "The crow," he says. "I like crows to begin with." This particular crow is named Edgar, and Croslin is a fan of the spunky creature. When Edgar was a chick, he fell out of the nest, and someone took him in and tried to raise him as a pet. "There's one thing you don't want to raise as a pet," Croslin says. "It's a crow." Apparently, they leave quite a mess in their wake, so if you don't want your prized possessions shredded, just bring the little squeaker to your local rehab center.

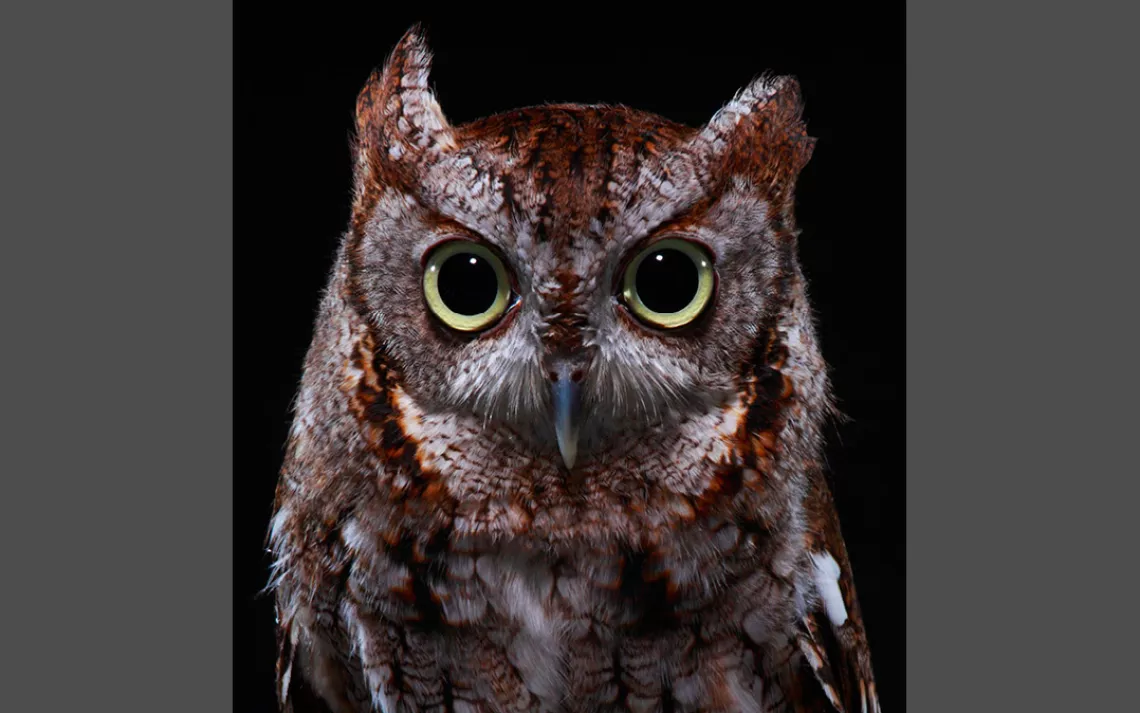

Screech Owl

Some of the owls that have found their way to the center fell out of their nest or were abandoned by their parents. Don't be fooled by this owl's big, round eyes and fluffy feathers into thinking it's a helpless little orphan. In the wild, the carnivorous birds are formidable hunters. "There comes a point where they're not so cute and cuddly when they're eviscerating a mouse," Croslin says. Screech owls are solitary birds and can be identified by their high-pitched whinnying on a late evening.

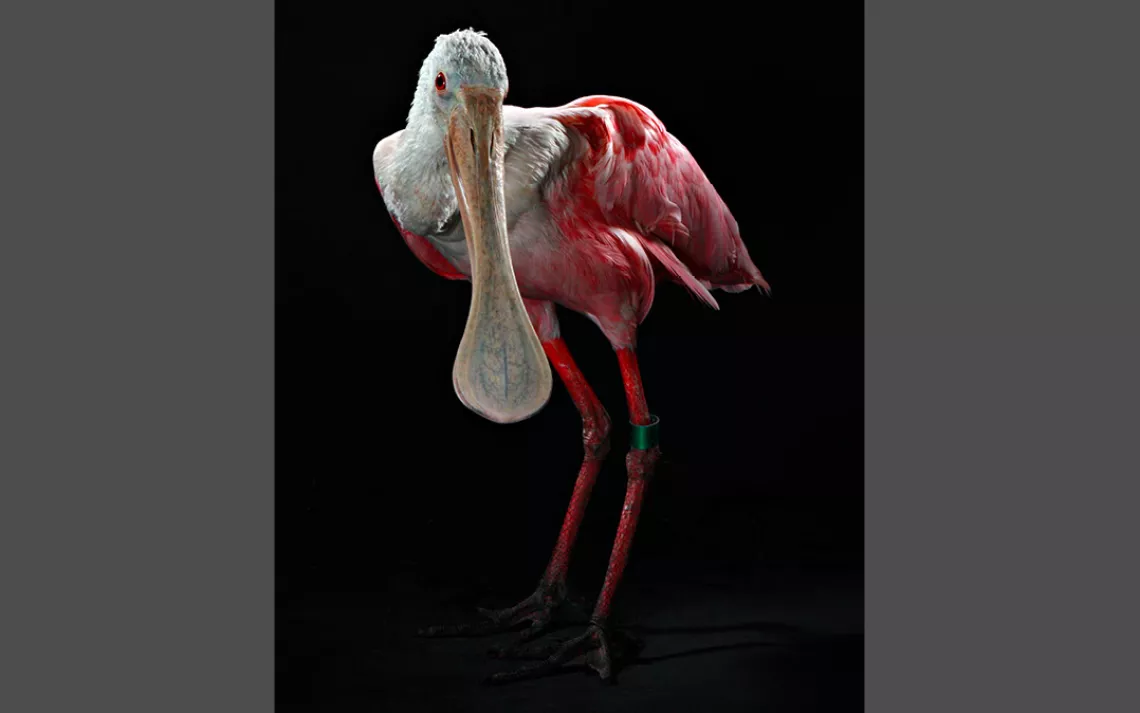

Roseate Spoonbill

The Muppet-like roseate spoonbill is a wading bird that uses its flat beak to scoop up invertebrates in the shallows. The band on its vibrant pink leg symbolizes that this bird is a permanent resident of the sanctuary.

Reddish Egret

A wading bird, this reddish egret—called Reddish—is completely habituated to people. "He's a little monster," jokes Croslin. Reddish egrets actively jump about and pounce after fish in the shallows, unlike most other egrets, which stand very still and wait for the fish to come to them.

Common Tern

The common tern is an elegant bird, with its pointed wingtips, orange beak, and forked, black hood. These birds nest in island colonies to protect themselves from terrestrial predators. Their bouncing flight is a lovely spectacle, as is their courtship ritual in the air and on the ground, during which the male brings offerings of fish to the female and they both carry out a series of poses and murmured vocalizations. Terns obtain their food by diving, usually for fish, but they also bring in arthropods and isopods to feed their young. To learn more, visit Project Puffin. Since this particular individual is flighted, Croslin says, he has a great chance of released back into the wild.

Red-tailed Hawk

Red-tailed hawks are the large yet understated raptors that can be found surveying civilization and searching for rodents from the perches of telephone poles. In keeping with its name, the adult sports a rusty red tail, along with a speckled band of black across its chest. Found in the rural countryside and city alike, the red-tail is the most widespread hawk in the United States. It's also pretty widespread on the silver screen, where its throaty scream is used most by directors in place of an eagle's.

Yellow-Crowned Night Heron

Known for making a loud squeaky gwak! as they fly away into the darkness, these nocturnal waterbirds can be found in both saline and freshwater ecosystems, where they nest colonially. Male herons initiate nest building in a courtship display with the female, where he carries sticks to build a nest as high as 60 feet or more. Adult night herons are a pleasing combination of gray, black, and buff. A yellow plume on the top of its head signifies breeding decor. As the birds get older, their eye color changes from orange to deep red.

The Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary admits as many as 8,000 to 10,000 birds per year, making it the largest organization of its kind in the United States. While the facility welcomes visitors, it took some effort to convince the folks at the sanctuary to allow Croslin to shoot these intimate portraits; they're highly protective of their birds, especially those they hope to return to the wild. "They'd never had a photographer come in to do something like this," Croslin says.

Stacey M. Hollis is an editorial intern at Sierra Club. She harbors a love of birds stemming from an early age and it has colored her life ever since. In addition to her passion for nature and work in environmental conservation, her interests include travel, good food, cycling, photography and people watching.Stacey has a Bachelor's in Biology and Environmental Studies from Warren Wilson College and a Master's in Journalism from the University of Oregon. To learn more, visit www.staceymhollis.com or find her on Twitter via @stacebird.

More articles by this author The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club