Inveterate Invertebrates

In Spineless, Susan Middleton's intimate portraits of marine invertebrates bring rarely seen creatures of the deep to luminous light

Photographs by Susan Middleton

At the very least, photographer Susan Middleton will make you rethink using the word “spineless” as an insult. The much bigger-picture results of her latest book are 250 magnificent, intimate photographs of rarely seen marine invertebrates—and the discovery of two new species: the kanaloa squat lobster and wanawana crab. Spineless: Portraits of Marine Invertebrates, the Backbone of Life (Abrams, 2014) is the result of seven years of fieldwork with marine biologists in Hawaii’s Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument, the Central Pacific’s Line Islands, and Washington's San Juan Island. Middleton took these shots in a "photarium" (a hybrid photo studio and aquarium) filled with fresh oxygenated seawater at the exact right temperature. She observes some of these marine supermodels in their new environment for hours before taking a shot. "Patience," she writes, "is the single most important aspect of my photography." Here are a few of the portrait sitters.

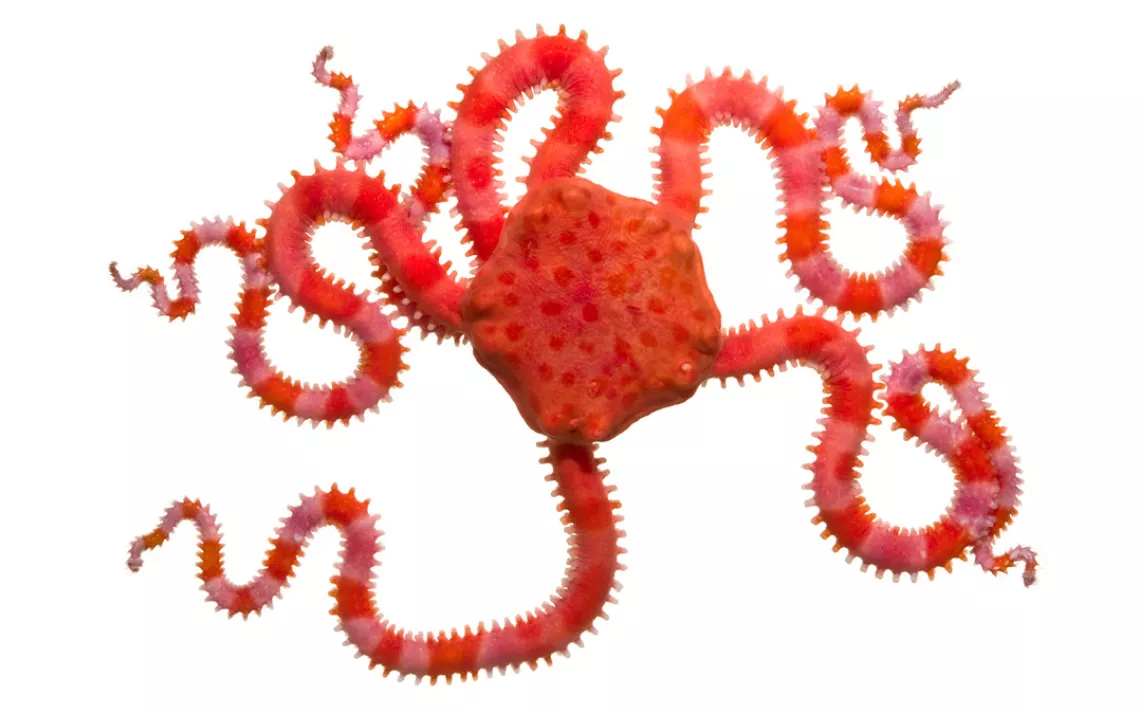

It may not have a head, eyes, or a face, but the pink brittle star (Ophiomyxa australis) does have five Seussian-colored legs—and it knows how to use them, choosing one as the lead limb and "rowing" with the others. Middleton says that when doing fieldwork at San Juan Island's Friday Harbor Marine Laboratories, she noticed that invertebrates from all the other phyla were afraid to get too close to the sea stars. "Sea stars are lovely to look at but are fearsome predators," she writes, adding, "they also lay eggs from their 'armpits,' defying human expectations of how animal should operate."

In her short film "Hermit Crabs!," Middleton calls Elassochirus tenuimanus one of her "favorite invertebrates" and gives us a behind-the-scenes look at a photo shoot with these tempermental models. "They just want to pull back in their shell. Or, they want to run around—very frenetically!" she says. "They do not respond well to direction."

When hermit crabs outgrow their shell, they have to move into a vacant one or evict a coveted shell's current tenant. Apparently, the hunt for a vacant shell in Hawaii is as fierce as the quest for a reasonably priced Honolulu apartment. This state of affairs is getting worse with climate change, as carbon sinks into the ocean waters, acidifying it and causing shells to dissolve.

Shown here is a widehand hermit crab, which measures in, with shell, at 1.8 inches.

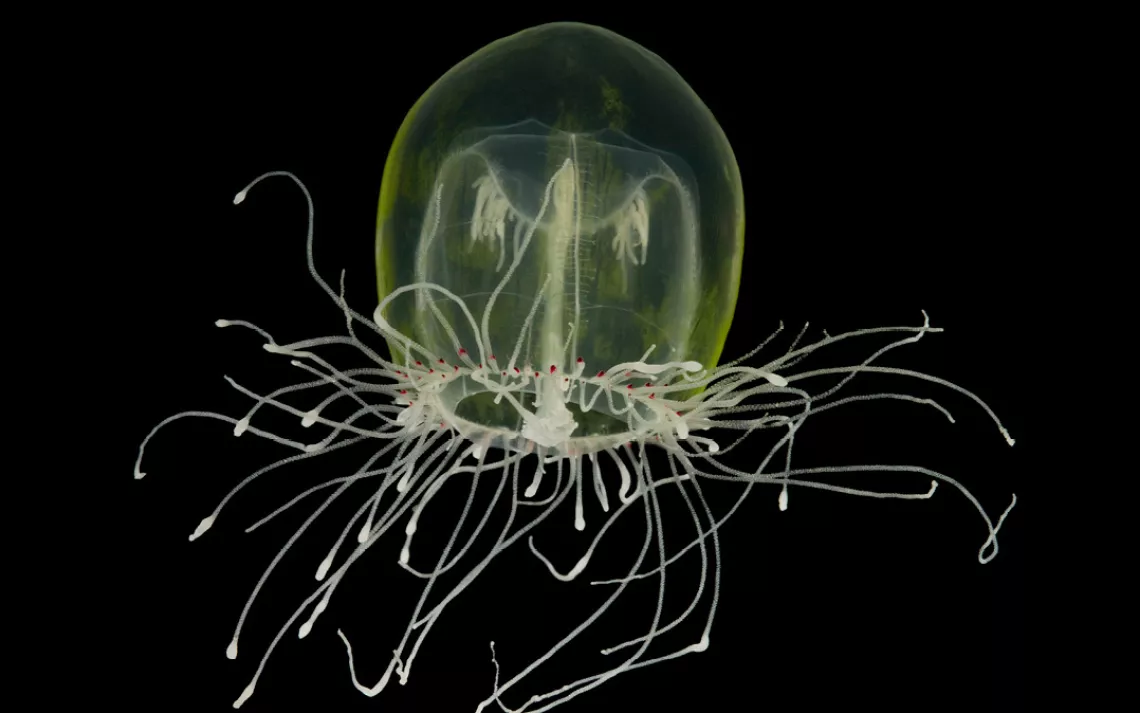

Could the red-eye Medusa (polyorchis penicillatus) be sent by Simpsons creator Matt Groening to take over the seas, while Kang and Kodos conquer Earth? Or does this transparent beauty have nothing up its sleeve—er, oral arms.

Named for the approximately 30 red light sensors that rim its bell, the jellyfish pulses upward to feed. Researchers have studied how its passive energy recapture gives it a Michael Phelps–like propulsive advantage over other swimmers.

There's no denying this stubby squid (Rossia pacifica) has a certain swagger. And while it's indeed stubby (about 2.5 inches, not including its eight suckered arms), it's not really a squid, or an octo-squid, but rather a closer relative of the cuttlefish. It likes the nightlife and spends most of the day buried in a bed of sand, poking a kaleidoscope eye out to watch for danger or perhaps food. Shrimp is its favored meal, which it chew with its small beak, just "like we eat corn on the cob," according to Octopus: The Ocean's Intelligent Invertebrate.

Opalescent nudibranchs (Hermissenda crassicorniscan) are beautiful, but they can be brutal hotheads, attacking and even eating each other. And they can be hard for other animals to pin down: Researchers have watched nudibranchs simply cast off their fingerlike projections, called cerata, and move on when kelp crabs grab hold of them; the cerata grew back in a few weeks. The Marine Detective has a delightful short video of a nudibranch-on-nudibranch fight that happens to get broken up by a decorator crab.

The white phantom crab (Tanaoa distinctus) is clearly overdue for a starring role in a cuddly horror film or for stuffed-animal fame. Even against a white background, every feature of this rarely seen creature—which lives at depths of up to 2,600 feet in the Pacific Ocean—stands out in Middleton's portrait. It was named for the Polynesian god of darkness, Tanaoa, who was said to be banished to the ocean depths after the creation of light.

Here, Middleton gives us a chance to see the colors of the frilled anemone (Phymanthus sp.) not as camouflage but as vivid in their own right—and a rare view of its column, which is usually buried. Those frilly tentacles will react to the slightest jostle by sending a neurotoxin-filled filament at prey.

Have a gold-banded hermit crab, hermit crab anemone, unidentifed anemone, Darwin's barnacle, and calcareous tubeworm ever looked so downright cute? As Edward O. Wilson wrote of Susan Middleton's portraits of rare and endangered animals and plants, "They speak to the heart. In the end their kind of testimony may count as much toward conserving life as all the data and generalizations of science."

By M.P. Klier

M.P. Klier is Sierra's copy chief.

More articles by this author The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club