Inside "The Human Element"

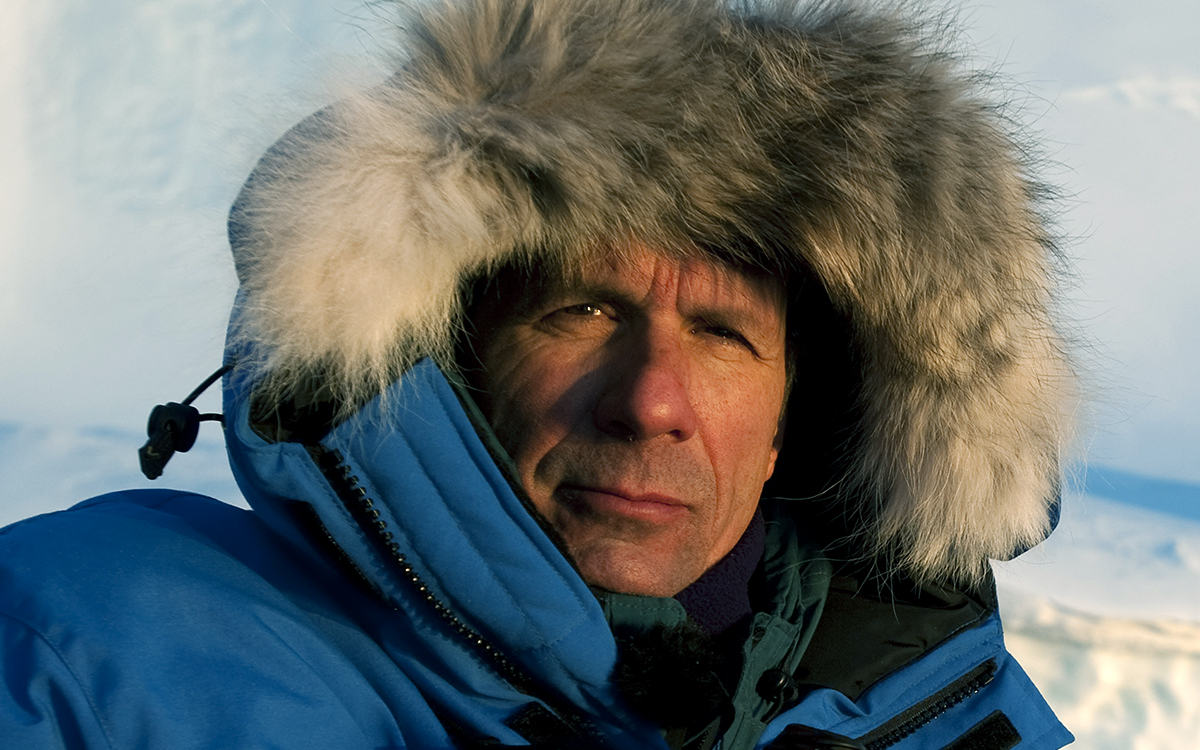

James Balog of "Chasing Ice" turns his lens on global warming’s human casualties

Photos courtesy of Earth Vision Film

Photographer and mountaineer James Balog was once a climate change skeptic. He changed his mind in 2005, after an assignment for National Geographic brought him to the Arctic. That first taste of ice inspired Balog to found the Extreme Ice Survey, leading a team on a mission around the northern part of the globe (from Nepal to Montana) to capture multiyear time-lapse footage of Earth’s shrinking glaciers. The resulting documentary, Chasing Ice, released in November 2012, received critical acclaim.

In his latest project, available now on DVD and major VOD platforms, Balog demonstrates even broader ambitions: He sets out to tell the story of climate change through the lens of not just ice, but all four of the classical elements. And so the film is split into four sections. The first retreads melting ice caps and discusses their consequences on the southeastern United States; the second shows the effects of air pollution on a community in Denver; the third focuses on the forest blazes of the West; and the fourth introduces viewers to Balog’s hometown, a coal community in Kentucky. What ties all these stories together, Balog states on screen, is the film’s fifth, titular element—The Human Element.

In his latest project, available now on DVD and major VOD platforms, Balog demonstrates even broader ambitions: He sets out to tell the story of climate change through the lens of not just ice, but all four of the classical elements. And so the film is split into four sections. The first retreads melting ice caps and discusses their consequences on the southeastern United States; the second shows the effects of air pollution on a community in Denver; the third focuses on the forest blazes of the West; and the fourth introduces viewers to Balog’s hometown, a coal community in Kentucky. What ties all these stories together, Balog states on screen, is the film’s fifth, titular element—The Human Element.

“My team and I have collected visual evidence of the epic changes facing the earth today,” Balog says in one scene, his voice distorted over the March for Science’s PA system. He’s referring to troubling images that appear on screen, among them a child half-submerged in water off the shores of Tangier, an island in the Chesapeake Bay under imminent threat of inundation. “They are meant to be symbols of the times we’re in,” Balog told Fresh Air.

Another child is pictured with a nebulizer pressed against her face; she attends a school in Denver specially designed to accommodate asthmatic students, their condition made worse by pervasive air pollution.

The film’s best moments take place when the people Balog meets tell stories about their lives and futures: Dave Schulte, a marine biologist with the Army Corps of Engineers, candidly discusses the cost of seawalls and the imminent necessity of relocating certain towns; in Denver, Yadira Sanchez says she doesn’t have the money to move away from her polluted neighborhood; a group of men in Kentucky outline their plan for a solar farm that could replace jobs lost from shuttering coal plants. These stories are compelling because they’re pressing, frustrating calls to action. The problem, viewers see, is so often right before our eyes.

This is part of what makes Balog’s task so difficult, even if he isn’t risking his life to bring back rare images from a hostile terrain. Chasing Ice’s Extreme Ice Survey lived up to its name, with Balog suffering a knee injury and cameras malfunctioning in the extreme cold. But in his new film he’s confronted not with a physical challenge, but rather one of affect. How can a photographer make us care about something that’s already visible to so many? The new mission sometimes leads to an awkward disjuncture; Balog takes his heroic outdoorsman persona and heavy-duty camera equipment into homes, schools, and graveyards, where he’s sometimes shown coaching his subjects to pose as symbols of disaster.

Though he’s interested in human intervention into nature, taking pictures allows Balog to operate at a bit of a remove. Rather than intervening himself, he observes and documents intervention; his hands are clean. But no one is outside of history, and Balog knows this. He dedicates the final act of the film to weaving together his own story with that of the planet. Balog was born and raised in coal country in Kentucky and credits his love of photographing conflict between people and nature to his early years spent examining the contrast between “beautiful forested hills” and “gigantic piles of waste rock that had been dug out of the mines.”

The narrator also explains, for those who could have possibly forgotten, that coal gave rise to more than just Balog’s photographic practice—a montage depicts the rise of industrial society, fueled by combustion. Like the rest of us, Balog is a product of a world built by fossil fuels. “Coal made me who I am today,” he says. Balog hopes that the same dynamism can be applied to something else: Optimistic statistics about renewable energy (it employs 360,000 people in the US at present) flash across the screen.

The film portrays humans as the victims, evidence, and perpetrators of the crime. But it also reminds that they (we) are the only hope for a way out.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club