Coal Ash Comeback

It’s headed back to drinking water and playgrounds, thanks to Trump’s EPA

In 2014, the Dan River Steam Station in Eden, North Carolina, released 39,000 tons of coal ash into the Dan River. Duke Energy agreed to pay $3 million for the cost of cleanup, which polluted 70 miles of the river with arsenic, lead, and mercury. With the new rollbacks from the EPA, Duke may be able to transfer future costs onto nearby communities. | Photo by AP Photo/Gerry Broome

On November 4, the Trump EPA rolled back Obama-era regulations that limited contamination from the 737 toxic coal ash sites in the US and Puerto Rico. The 2015 Coal Ash Rule pushed to close unlined ponds and landfills where coal ash—the contaminated residue of burning coal to produce electricity—is stored. The practical effect of the rollback is that most utilities won’t have to clean up their toxic lagoons. And when the lagoons leak, the rollbacks also weaken measures meant to check water pollution. According to the EPA itself, at least 30 percent of industrial water contamination in the US comes from coal-fired power plants. Ninety-five percent of these plants have unlined ponds, and almost all coal ash sites are polluting groundwater above safe drinking-water standards.

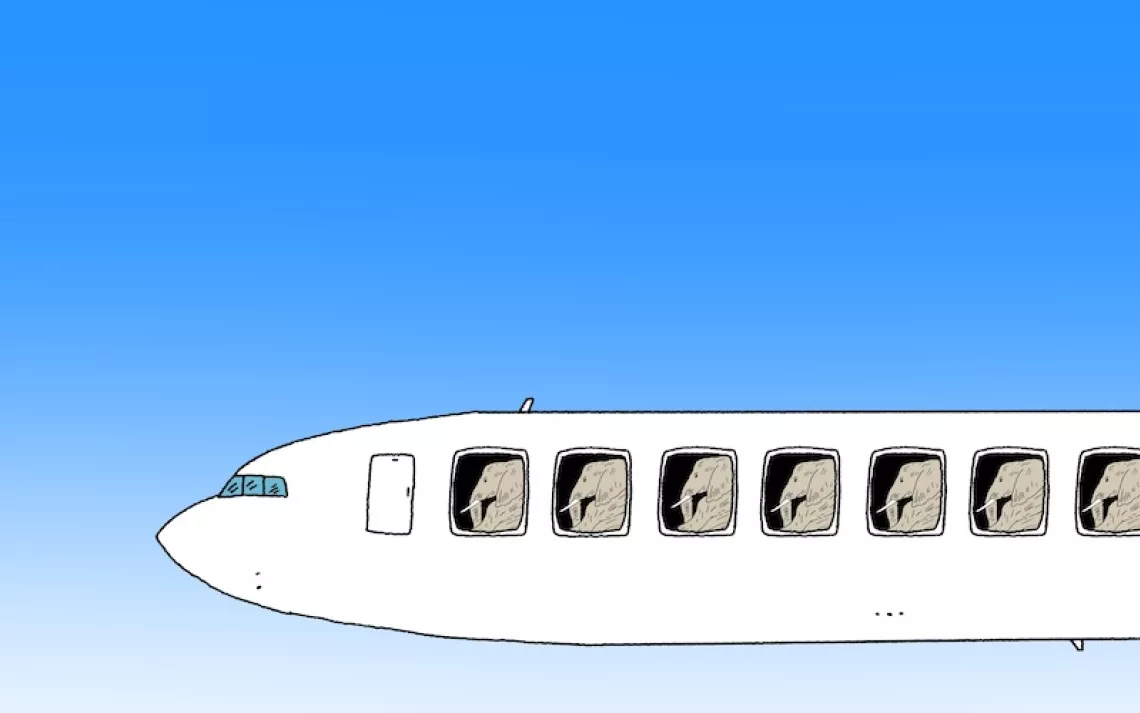

Attempting to justify the move, EPA administrator Andrew Wheeler said that the old rule placed “heavy burdens on electricity producers across the country.” The new rules let industry generate revenue from coal ash, allowing its “beneficial use” in landscaping and structural fill, including sports fields and playgrounds.

But according to coal ash experts, Wheeler’s claims that the revisions “protect public health and the environment” are phony.

Avner Vengosh, professor of earth and ocean sciences at Duke University, says the rollbacks lack any scientific support whatsoever and that the EPA “should be ashamed.” For Vengosh, even the 2015 rule was a compromise because, under industry pressure, it failed to define coal ash as hazardous waste. Instead, even though coal ash contains toxic substances like arsenic, lead, mercury, and selenium and is linked to a variety of health problems including birth defects, cancer, and damage to every major organ system, it is regulated like household waste. A new study by Vengosh has even linked coal ash leachate in freshwater to increased levels of hexavalent chromium, the toxic form of chromium Erin Brockovich famously campaigned against.

Coal ash spills are disastrous, and costly, for communities. In 2014, Duke Energy released 39,000 tons of it into North Carolina’s Dan River, and in 2008, a Tennessee Valley Authority site near Kingston, Tennessee, buried the town of Swan Pond and the Emory River in 1.5 million tons of coal ash. The subsequent cleanup effort violated a laundry list of safety protocols and sickened more than 400 workers—42 of whom have died from illnesses linked to their exposure.

While those spills were linked to negligence, Frank Holleman, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, said that coal ash pits also “threaten catastrophes every time there is a hurricane, flood, or a storm.” That is obviously worrisome given the increased frequency and severity of flooding and rainstorms, as well as the intensifying of tropical storms, that come with climate change. 2017’s Hurricane Matthew and 2018’s Hurricane Florence both led to coal ash spills in North Carolina, and those are only the spills we know about. As Lisa Evans, attorney for Earthjustice told Sierra in September, these disasters are “entirely preventable, but the Trump administration lacks the will to require industry to shut these sites down.”

With the new rollback, Vengosh worries about communities living next to coal ash sites. While the 2015 ruling gave limited protections, “this ruling takes it away from them,” he said. “They’re on their own again. There’s not any safeguard or protection.”

Instead of relying on the EPA, states could take a larger role in protecting their constituents. After the 2014 Dan River spill, North Carolina’s Department of Environmental Quality created its own coal ash law in lieu of federal regulation. In April, the department ordered Duke Energy to excavate all nine of its remaining coal ash basins. Duke continues to appeal the ruling, but judges have twice ruled in favor of the state.

But in states with weaker regulations, utilities are already using the proposed rollback to their advantage. TVA announced it wouldn’t excavate a coal ash pond at Bull Run Fossil Plant unless ordered to do so. Just over 30 miles from the Kingston disaster, the unlined clay pit holds 5 million tons of coal ash next to the Clinch River, a public drinking water source, and is partially submerged in groundwater.

The EPA rollbacks are a gift to a dying industry, but may not be enough to save it. (Last month Massey Energy became the ninth coal company to declare bankruptcy under the Trump administration.) Betsy Southerland, a former EPA official and writer of the 2015 rule, told Newsweek that she thinks the courts will kill Wheeler’s revisions, but while possible litigation drags out, “their rules will be fact.”

According to Vengosh, the rule change transfers the cost of contamination from the company to the public. “Even if companies aren’t responsible for taking care of coal ash contaminants, they’re not going away,” says Vengosh. “Someone has to take responsibility.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club