Life Above the Treeline

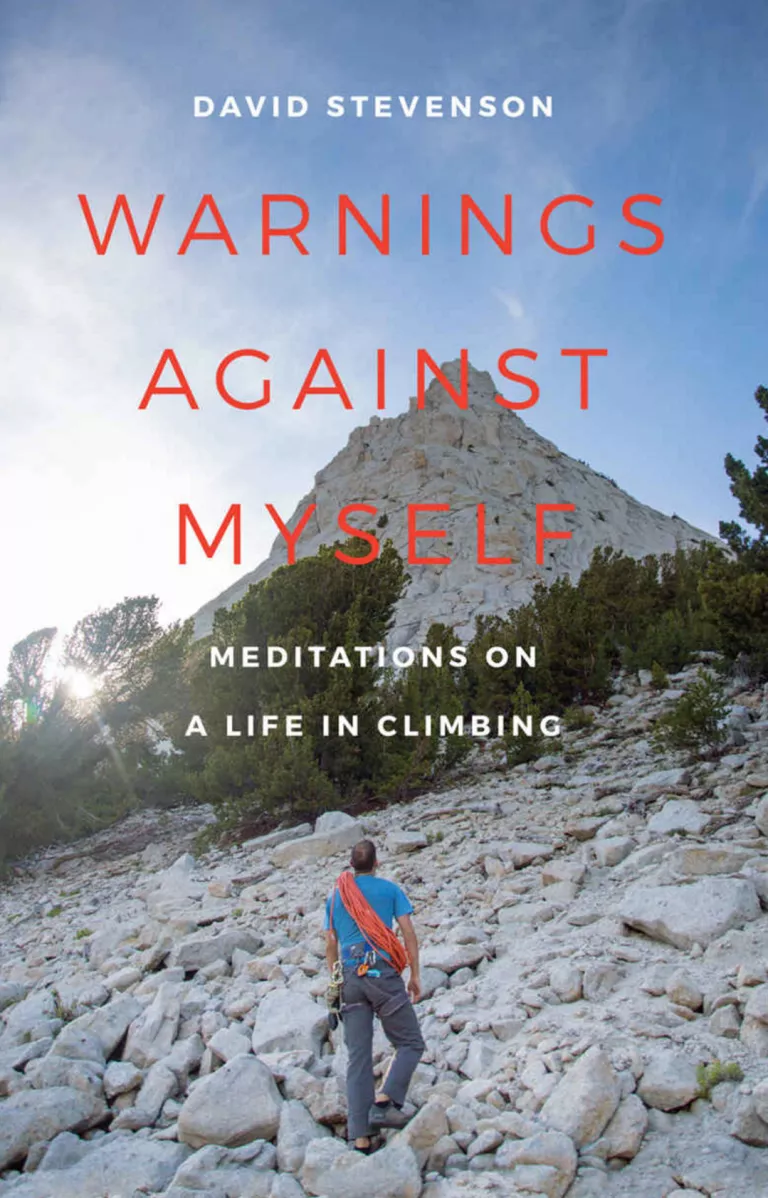

Warnings Against Myself: Meditations on a Life in Climbing by David Stevenson (University of Washington Press, March 2016)

It is high time that the mountains took their place among the great soulful practices of humanity. We do, after all, hold the heights to be sacred and mysterious for a reason. There is more art than sport to climbing. David Stevenson has spent a goodly portion of his life above the treeline and knows a thing or two about the mountains and the world. His compilation of climbing and mountaineering essays, Warnings Against Myself, is the writing of a lifelong alpinist working to elevate climbing into a broader cultural tradition. There’s no braggadocio here—Stevenson is self-professedly dedicated and studious rather than extreme, which is an excellent vantage for a writer. You shouldn’t have to solo Astroman or the north face of the Eiger in order to write a good climbing book.

Stevenson is at his best when he turns a simple moment into something large and powerful. Pairing his son’s first glacier with Robert Frost’s “Earth’s the right place for love” is a quiet and beautiful conjunction of place and sentiment. The glacier is otherworldly, an ice palace full of trapdoors that have snared other climbers. His son is fragile and super confident in the way of teenagers. Stevenson is in the middle of all that possibility and grace and peril, watching the world turn around him.

Unfortunately, for much of the book Stevenson marches his readers through so many literary references that his own stories and reflections are lost in the bushwhacking. As a sign of what’s to come, his first pages hopscotch from Borges to David Roberts to J. Alfred Prufrock with little reflection between. In an essay about language and climbing codes, he summons Heraclitus and Jacques Derrida for a perfunctory effort to deconstruct sport climbing—which could have been hilarious (I’d love to read a send-up conversation between the dark prince of French philosophy and, say, Jerry Moffatt) but instead feels dry and forced. Stevenson sprinkles quotes into his writing like a man with a bag full of rocks; too many land with a clunk.

Where Stevenson stays with one climber or idea longer, he taps into deeper essentials of the climbing community. Often he writes as the outsider looking in, knowing more than enough to fully appreciate what his climbing heroes have accomplished without having personally experienced the full-scale abandon (of family or career or fear of risk) with which climbers like Dougal Haston or Ron Kauk live their lives. In one perfect moment from the essay “Untethered in Yosemite,” Stevenson acts as an uncomfortable conduit between a Yosemite lifer and the outside world. He has one foot in the pure-mountain world, the other in the shifting other realm of people and politics, and the dislocation he feels riding those crosscurrents is apparent. These sections are charming, funny, and deeply human.

Stevenson ages over the course of his book. The essays included span 25 years of his writing life and 40 years of his climbing life. Physically, certain climbs become more difficult with the passing decades. Mentally (in an interesting reverse progression), other routes become easier; what struck the 20-year-old Stevenson as a death route becomes a quick march at 40. With that long trajectory of life and climbing behind him, I wanted to know what exactly he sees when he looks at a mountain now, having looked at them for most of his life. Do the mountains still seize him in the same way as when he was young, or has their grip changed? Stevenson doesn’t answer that here. And I was left to wonder about his relationship with risk. Fear is palpable throughout the book (even in its title) but never openly aired, as if it were taboo.

Warnings Against Myself is a slippery sort of book. There are flashes of brilliant writing (“In Yosemite the golden age is recent enough that the gods mingle casually with mortals, as if they were not gods at all” and “This is the week of the Northern Solstice, when time becomes unhinged”). There are also long stretches of desert. Throughout, the warnings of the title remain elusive, or at least unresolved. Stevenson is being warned, but whether those cautions are coming from the mountains or from himself, and whether they are directed at the climber, or husband and father, or simply to a person whom the mountains will change for better and worse, is difficult to say. The possibilities come through as hints, but the hints stay vague.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club