Is Climate Mitigation a Good Investment?

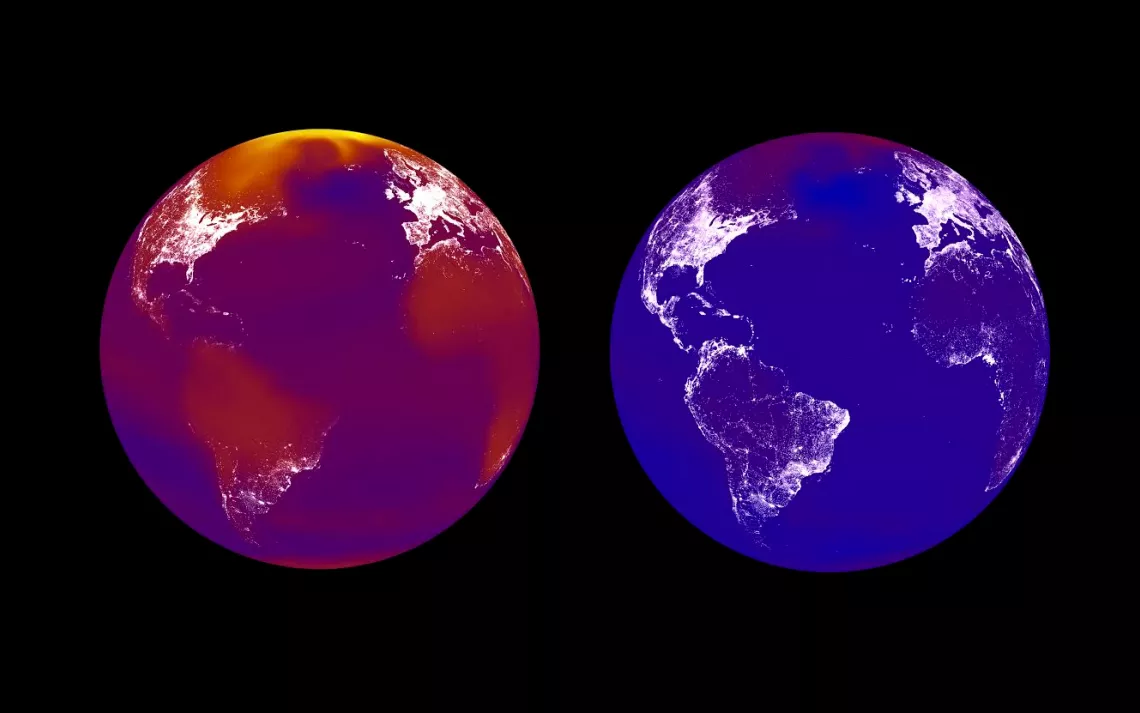

Here we see two possible futures. The left shows temperatures in 2100 if we continue on our current path, while the right shows temperatures under aggressive and immediate climate action. | Image by Burke, Hsiang, & Miguel (Nature, 2015)

A team of researchers at Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley has managed to put global warming into terms that even Donald Trump would understand. Their study, published in Nature last month, evaluates the financial toll that rising temperatures will have on the global economy over the next century.

The authors—Marshall Burke, Solomon Hsiang, and Edward Miguel—collected data on 166 countries from the past 50 years to understand how economic output has responded to changes in temperature historically. Then, they combined these approximations with future climate change projections in order to estimate how temperature will affect global economic growth over the next century. The study does not take the economic cost of rising sea levels and natural disasters into account.

Some environmentalists may balk at the notion of evaluating our action or inaction on climate change in monetary terms, but these researchers are asking an important question: is climate mitigation a good dollar-for-dollar investment?

The study concludes that if climate change goes unchecked over the next century, U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) per capita will drop 36 percent by 2100. To put that in perspective, consider that during the Great Depression—the worst financial crisis in our nation’s history—our GDP fell 30 percent.

The same unmitigated climate scenario will see the average earth-dweller’s income tank at least 23 percent.

But why, exactly, are rising temperatures bad for the global economy?

According to Burke, warmer temperatures reduce agricultural output and labor productivity, worsen health outcomes, and increase the likelihood of violent crime and civil conflict—all factors that can significantly reduce a country’s overall economic productivity. The results show that negative consequences like these start to kick in once a country moves past the optimum average temperature for economic productivity—about 13 degrees Celsius (or 55 degrees Fahrenheit).

The global wealth gap is also projected to expand significantly as the planet heats up. The study estimates that by 2100, climate change will have reduced average income in the poorest 40 percent of countries by 75 percent. “In the modern era, a 75 percent drop in income is what a large-scale war would do to an economy, only wars happen abruptly and recovery can often be just as fast,” explains Hsiang. “With something that proceeds as slowly as climate change, countries will be set back long-term.”

Meanwhile the richest 20 percent of countries will have experienced slight economic gains by 2100. This disparity emerges in the study’s simulations because colder countries, which also tend to be wealthier, move closer to the 13 degree Celsius optimum average temperature as the climate warms. But temperatures in warmer countries, which are typically poorer, already exceed that, so rising temperatures would be detrimental to their economies.

But doesn’t that mean that the United States, with all of its wealth, will be spared the negative effects of climate change? Unfortunately, no. Its average temperature is already around 13 degrees Celsius—what one press release called the Goldilocks temperature (not too hot, not too cold). Warming temperatures will take it out of this range and into the danger zone.

"Our results suggest that high-emissions countries like the United States and China have a lot more to lose from climate change than previously thought," explains Burke.

So, the short answer to whether climate mitigation is a good long-term investment is yes. We environmentalists don’t need convincing that climate mitigation makes sense, but when it comes to policy-making, putting a price on climate change might make all the difference.

"…Transforming the global energy system is not a trivial task,” says Hsiang. “But this paper is helping us see that, from a policy or business standpoint, climate mitigation is a really good investment.”

"We hope that our results will help bring these really large high-emitting economies to the negotiating table," adds Burke, speaking of the upcoming 2015 United Nations Conference on Climate Change in Paris.

You can visit the study’s online portal to see how climate change will affect GDP per capita in the country where you live.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club