How to Support Clean Energy and Not Be a Jerk

As the nation turns away from coal, what do we owe coal workers?

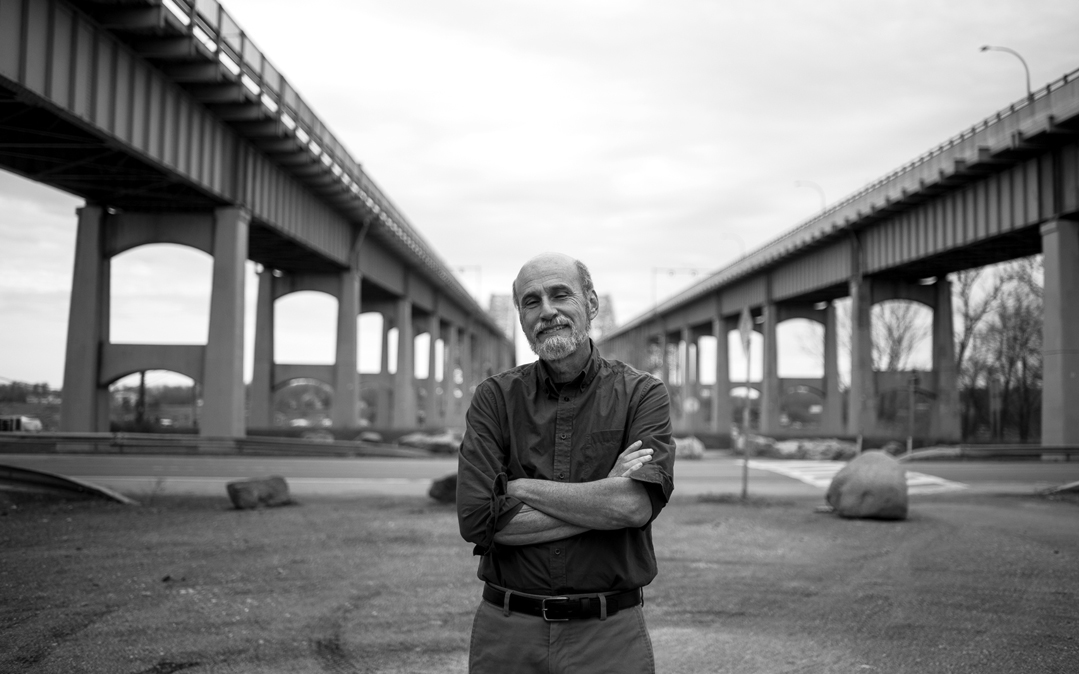

Photographs by Shawna Stanley

MICHAEL PHILLIPPI MAKES $28.50 per hour working as a mechanic at Murray Energy's Monongalia County coal mine in West Virginia. That's almost double what he made as a crane operator before snagging this coveted job four years ago. With healthcare and pension, that figure is close to $60 per hour, all because he's a member of the United Mine Workers of America (UMW). That's a hefty paycheck in a state where the minimum wage is $8 per hour and the poverty rate is one of the highest in the nation.

The amiable, broad-shouldered Phillippi brings home more than twice what his wife makes as a teacher's assistant. He puts 10 percent of his paycheck into a 401(k) and invests another chunk in education savings for his three kids. He pays the bills and still has enough left over for a boat and a little camp where his family spends time in the summer. "I know guys making eighteen, twenty thousand," he says. "We had a banker start a few months ago—he was in charge of loans at a bank. He makes more money and has better benefits as a coal miner."

If the mine closed, Phillippi says, he'd have to learn to live off $15 an hour or less. To find a salary comparable to his current job's, he'd have to drive 75 miles north to Pittsburgh. But he probably wouldn't. "I won't move," he says. "I am from here. My family is from here. My grandparents are from here. My wife and her family. This is our community. I want to raise my children here. I plan on dying here. It's the sad truth that the good jobs aren't here."

Phillippi's paycheck also matters to the small businesses he sprinkles money on, like the mom-and-pops he stops at on his 35-minute drive from his home in Morgantown to the mine. Sitting in a small conference room in the UMW regional office in Fairmont, Phillippi points across the table to Mark Dorsey, who worked underground for 34 years before retiring in 2010: "For every hour I work, I'm helping to pay his pension."

There are hundreds of thousands of Michael Phillippis spread out across the nation, from the coalfields of West Virginia and Kentucky to the more than 500 coal-generating power stations located in virtually every state. These workers now face the loss of their good-paying jobs due to the declining competitiveness of coal compared to other energy sources and new Environmental Protection Agency regulations intended to address air pollution and climate change.

Those regulations, of course, have clear benefits for Phillippi, Dorsey, and everyone who breathes. Stronger soot standards alone would prevent 35,700 premature deaths per year and 1.4 million cases of aggravated asthma. Shifting to renewable energy, says the Union of Concerned Scientists, would create three times as many jobs—although likely not as well paid—as an equivalent investment in fossil fuels. And the value of avoiding catastrophic climate change is incalculable.

But it won't pay the mortgage. As the coal industry withers, what will happen to Phillippi, Dorsey, and the communities they live in? The classic free market answer: That's life. Economies change, so suck it up. When the car replaced the horse and cart, buggy manufacturers moved on.

That is not the only answer. Slowly, tentatively, unions and environmentalists are beginning to talk about an entirely different option called Just Transition, a guarantee that the cost of bringing down the curtain on the coal industry will not be paid by coal workers alone, but will be spread across society. It would be a huge undertaking, ideally encompassing the tens of thousands of workers directly employed in coal, from mining to electric-power generation, plus the communities that depend on their spending and taxes.

Visions for what a Just Transition might look like vary widely. President Barack Obama's 2016 budget, for example, includes $55 million for his Power Plus plan, which features investments in economic development, job creation, and job training—a laudable commitment, but just a drop in the Just Transition ocean. On the other end of the spectrum is a plan like the one being proposed in the United Kingdom by a coalition of environmentalists and labor, promising that "anyone who loses a job in an old high-carbon sector like mining, oil, power stations, or car sales must be guaranteed a permanent [climate] job at the same rate of pay." The cost for a comparable plan in the United States could easily run into the trillions of dollars—not that anyone is rushing to pay.

Erin Heaney, executive director of the Clean Air Coalition of Western New York.

FOR COAL WORKERS, JUST TRANSITION can sound like planning your own funeral. In Tonawanda, New York, the discussion is proving as painful and difficult as you might think. This area just outside the city limits of Buffalo has been living in economic fear for generations as its industrial base has evaporated. Steel mills and auto factories have closed, manufacturing jobs have vanished, and property values have imploded. Buffalo, home to 600,000 people in 1950, had lost half its population by 2000.

Tonawanda is home to the Huntley Generating Station, owned by NRG Energy. The plant's two remaining coal-fired units operate at just 28 percent capacity, and the plant has mostly run in the red since 2009. At its coal-fired plant in Dunkirk, 60 miles to the southwest, NRG is investing $150 million to add natural gas as an option. Amount to be invested in the Huntley plant: zero.

Although it might seem obvious that the Huntley plant's prospects are dim, that doesn't make the conversation about transition easier, or less fraught. The Clean Air Coalition of Western New York (CAC) has been trying to start such a discussion but ran into trouble when it released a report, in January 2014, saying that the plant was not likely to remain open. That angered workers at the plant and their union, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, who feared that such an admission might hasten the plant's closing. "You go through the plant and talk about environmentalists, you don't get a good response," says Phil Wilcox, an IBEW representative. "The anxiety is high because the generators are not running when you go to work. You've got a mortgage and bills to pay and one marketable skill. [CAC] came out with the study that said the plant was going to close—the owners weren't saying it. It was not well received."

Erin Heaney, CAC's 28-year-old executive director, admits that more hand-holding might have helped. "The environmental movement has done a really crappy job addressing these issues," she admits. "We knew people would be upset; it was inevitable. We were delivering bad news."

After the bruised feelings healed, CAC helped organize a series of meetings involving community members, environmentalists, and members of the local teachers union and the Western New York Area Labor Federation to plan what a Just Transition might look like. (To date, those meetings have not officially included the workers or the IBEW.) The tension has eased, but the parties are still wary of perceived slights. There is also a generational and cultural gap: Older, more traditional union leaders often find it hard to cede leadership to—or accept advice from—smart young women like Heaney.

An atmosphere of suspicion and fear suits NRG Energy just fine. The company refused to let me interview workers; according to the union, employees would be subject to discipline even if they spoke to me on their own time at home. And the day before I had hoped to meet with workers and union representatives, a copy of a newspaper article in which a Sierra Club representative called for the closing of a coal-fired plant 150 miles away was circulated at a union meeting. Because the article created, as an IBEW representative said, "enormous hostility from those whose livelihoods are threatened," my meeting was canceled.

Bucking the prevailing skepticism, some labor leaders are supportive of Just Transition. One such is Richard Lipsitz, president of the Western New York Area Labor Federation. A retired local Teamster official, Lipsitz is mindful of balancing the interests of many constituencies, including the IBEW, but is also clear about the reality. "Because of a lack of a clear alternative," he says, NRG "can scare the hell out of people. Transition can't be done unless we show how we can save jobs and communities that will be devastated. The picture isn't pretty when the economic activity goes away and there is nothing to replace it."

The local teachers union has a keen interest in Just Transition because the school district depends on an annual tax allocation based on how much power the Huntley plant generates. In 2013, the allocation was $12 million; a year later, it had plummeted to $3.1 million. That cost the local affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers $1.2 million in concessions, in the form of higher healthcare payments and salary givebacks.

Peter Stuhlmiller is president of the teachers union. In the beginning, he says, "I distanced myself from the CAC because we still believed Huntley might stay open. I thought that any discussion of the plant closing would be a self-fulfilling prophecy." He has now come around, and credits Heaney and Lipsitz. "It's stupid not to prepare for the inevitable," he says. "We have to have the conversation now before it's mothballed. We need to prepare the community. Dick [Lipsitz] went out on a limb. He said, things are not good, and we need to sit down. He brought a breath of fresh air."

The CAC-led alliance is inching along, but soon must confront its toughest challenge: Where are comparable middle-class jobs in a post-coal economy? The best-paying jobs for workers in the last half century came about because unions leveraged power to bargain for good wages and benefits. But with private-sector union membership declining, wages have stagnated, and jobs at Walmart have become the new standard. You need only drive around Tonawanda, New York, or Fairmont and Morgantown, West Virginia, to appreciate the domination of the Walmart/Dollar Store/fast food economy. Pensions? Healthcare? Forget it. "What you are looking at," says Phil Smith, director of governmental affairs for the UMW, "is the reduction of the standard of living of every energy worker in the country."

When unions had significant leverage, they could ease transitions by making sure workers were taken care of. In the 1990s, a powerful hospital workers union in New York gave up wage hikes in return for a Job Security Fund, which guaranteed full pay for 18 months while workers took retraining classes and looked for new jobs. When new computer technologies replaced hot type, unionized pressmen working for the New York Times negotiated lifetime salaries.

In Buffalo, some Huntley workers are pinning their hopes on a project by Solar City to build the largest solar factory in the Western Hemisphere. With a $750 million state grant and $5 billion of its own money, the company promises 3,000 permanent jobs in a new 1.2-million-square-foot production facility on the site of the now-shuttered Republic Steel plant.

It sounds like a dream solution—except for the fact that no one knows what the solar workers will be paid. Over the past three years, solar cell prices have dropped by half, driven in part by rock-bottom wage rates in China. Labor costs there are now rising, but even so, it's hard to imagine Solar City paying wages and benefits comparable to what the Huntley workers make now. Solar City declined to provide projected wage rates for its Buffalo facility or current wage rates for production or assembly workers elsewhere.

Richard Lipsitz, president of the Western New York Area Labor Federation.

IN A MARKETPLACE WHERE UNIONS are weak and wages stagnant, a Just Transition would require major public investment. It wouldn't be the first time. As the Cold War ended, employment in the defense industry fell by a third—affecting almost a million highly skilled, unionized, well-paid manufacturing workers. In response, the Clinton administration allocated $16.5 billion between 1993 and 1997 to try to match workers with jobs appropriate to their skills or retrain them for new jobs.

Sadly, that effort largely failed. Laura Powers and Ann Markusen of the Project on Regional and Industrial Economics at Rutgers University found that most of the displaced workers ended up at lower-paying jobs, and that "a sizable minority has experienced a drop in earnings of 50 percent or more." What failed, Markusen told me, "were explicit efforts to reemploy workers. The efforts that were tried weren't well conceived and were not funded. Lots of new jobs were created in the 1990s, but they weren't targeted at defense workers, and many were less well paid."

A comprehensive Just Transition might invest in job training but, given the realities of the 21st-century job market, would also commit to full income, pension, and healthcare support for workers who found themselves in lower-end jobs. Such a program would be expensive, but there is precedent. After World War II, the GI Bill poured more than $129 billion in today's dollars into helping the 15.4 million returning veterans. The program provided a living wage and tuition to 2.2 million GIs who entered college and graduate school, with another 5.6 million choosing trade schools and other programs.

Money spent on Just Transition would not be a loss. For every dollar that was invested in the GI Bill, the economy reaped nearly $7 in economic growth and taxes. Funds invested in Just Transition would flow back into communities, sustaining families and boosting local economies.

Such a program would obviously be a hard sell in a Congress full of climate change deniers and deficit scolds. On the other hand, the labor movement has recently been energized by an audacious call for a $15-an-hour minimum wage, far beyond what many mainstream leaders considered prudent or achievable. Just Transition could be similar—a plea for a world where workers and their communities do not pay the price for corporate and national policy decisions, a campaign that could create an enduring link between environmentalists and labor. Climate change is already altering our physical landscape; planning for a Just Transition could shift the political landscape as well.

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign.

Quality Careers, Cleaner Planet

The Sierra Club supports a fair and just transition to clean energy, with job security and livelihood support for affected workers, preservation of pensions and healthcare, and training for jobs in other industries—ideally unionized—with similar pay and benefits. The Sierra Club is working toward this larger goal in sometimes-small steps, even as Club activists and attorneys target coal plants for closure.

In the 2013 shutdown of the Big Sandy plant in Kentucky, for example, the Club insisted on and won concessions from American Electric Power to ease the transition for the community. These included funds for economic development and for weatherization and other energy-efficiency programs, in order to stretch utility dollars. In Michigan, the Club opted to forgo a quick shutdown of the River Rouge coal plant in order to develop relationships with local leaders and work toward a transition plan.

And when the closure of the giant coal-fired power plant in Centralia, Washington, was negotiated, the Club, together with affected unions, insisted that a multimillion-dollar package for workers and the community be part of the final deal. (See "Kick Coal, Save Jobs, Right Now.")

The other side of the Just Transition equation is job creation. A report from the University of California at Berkeley noted that a partnership between the Sierra Club and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers helped lead to more than 15,000 green jobs in California's solar industry alone. Workers building solar arrays earn an average salary of $78,000 per year, plus healthcare and other benefits. Nationwide, median wages in the clean energy sector are 13 percent higher than those in the broader economy. Key to this employment boom, the report said, were the policies advocated by the Sierra Club/IBEW alliance: strong state and national clean energy policies coupled with "high road" practices favoring good-quality jobs, strong prevailing-wages laws, and union apprenticeship programs.—Paul Rauber

What You Can Do

Ask your senator to support the Obama administration's Power Plus plan; it's a first step toward providing support for coal workers and communities. Click to learn more.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club