Capturing the Wilderness: An Interview with Peter Essick

For Peter Essick, a world-renowned nature photographer, capturing the Ansel Adams Wilderness area meant long spans of solitary days in the high Sierras—and all the beauty and adventure that entails. Some of the winter shots required the most daring he’s ever needed in his 25-year career, including one memorable past snap of a radioactive alligator from a project on nuclear waste. Digging his own snow cave and trying not to suffocate during a four-day blizzard was worth it to Essick, who in his new book, The Ansel Adams Wilderness, celebrates Adams’ work. Ansel Adams changed the face of nature photography and shaped America’s relationship with our landscapes, and also influenced Essick himself when he was a burgeoning young photographer. Inspired to do the project by a reprint of one of Adams’ early books, Essick discusses the experience with Sierra: reliving an earlier era of photography and bringing us all back to a simpler time.

Sierra: In the forward of the book you talk about the potential intimidation of following in the footsteps of Ansel Adams. How did you overcome that?

Peter Essick: I had to believe that I could do something new and different. If you feel like it’s all been done already it can be really defeating from a creative standpoint. The more I thought about it, the more I realized that I could make it my own. I took a more contemporary approach and included the modern context of today's wilderness.

Some people, even some artists, look at nature as sort of outdated and a pleasant day-dream. I wanted to emphasize that it's still relevant and we need it just as much as we did back then. We just need to look at it with a different lens. I think a lot of the people who pick up the book may have the Ansel Adams photos in mind and feel like they already know it—I knew I could give them a different perspective. Adams always used the latest technology, so using digital is something that I felt like he would do if he were here. I didn’t want to copy his technique or his approach but I wanted to celebrate it while bringing it into the modern era.

S: How do you think the landscape has changed since Ansel Adams photographed it?

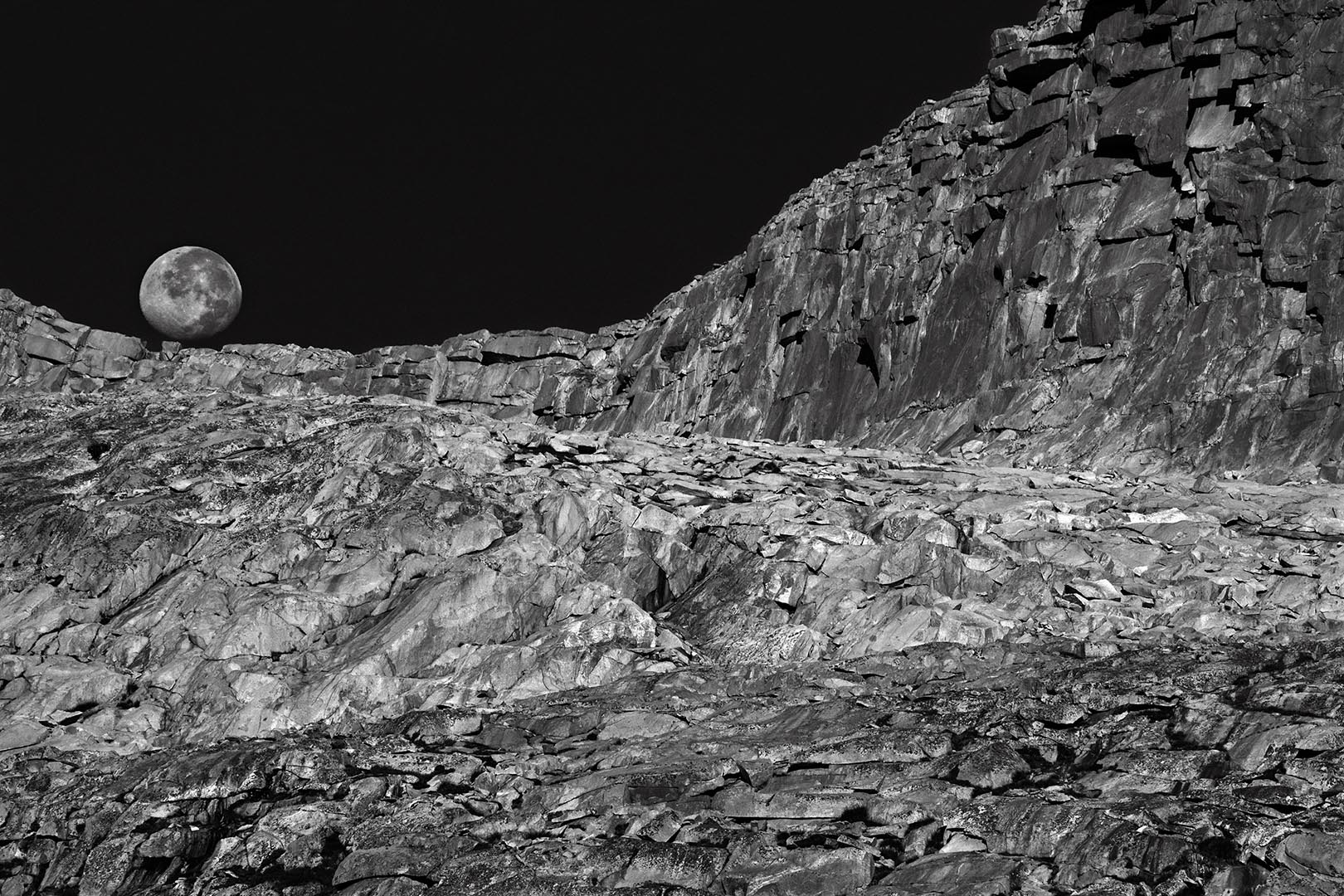

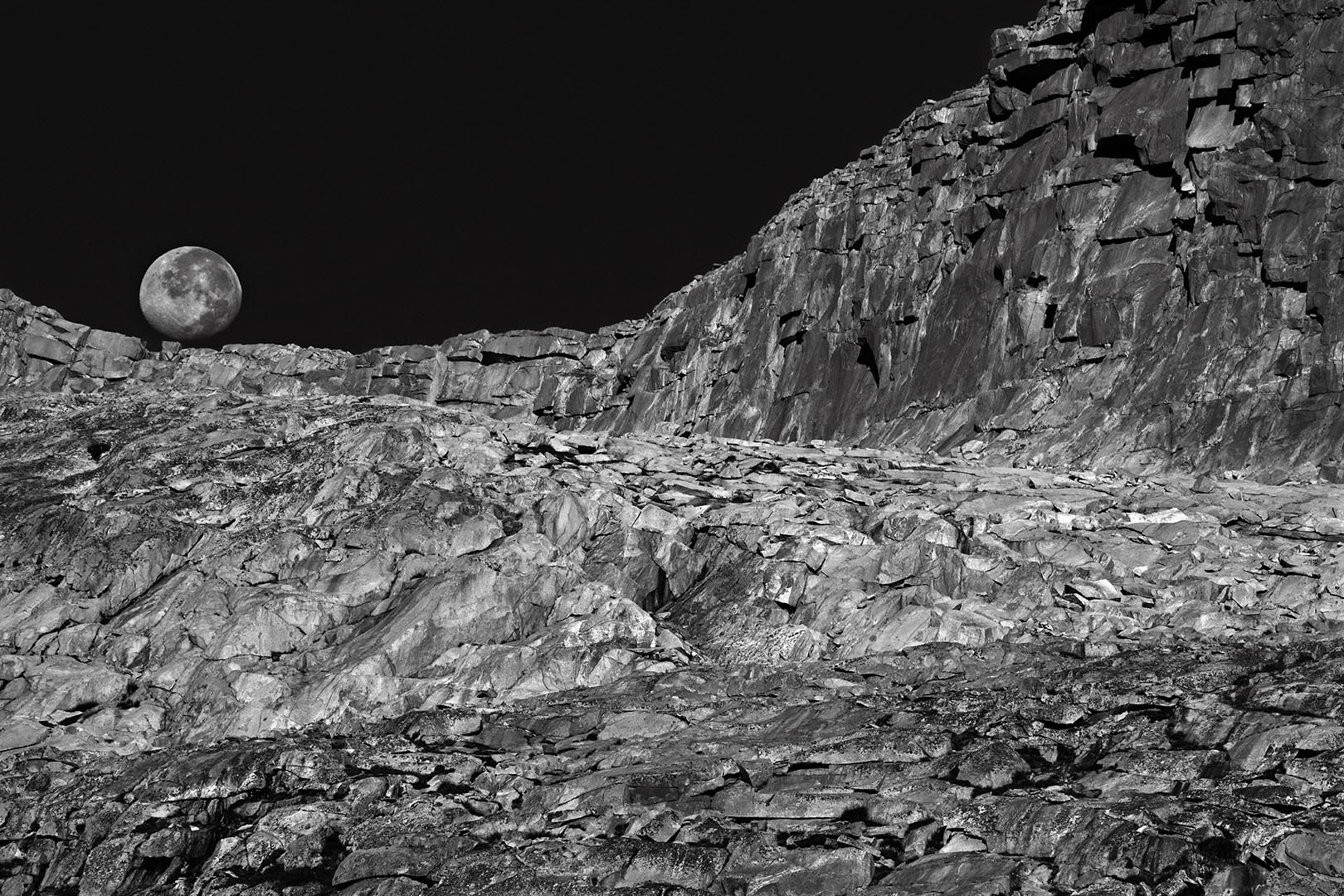

PE: There are some pictures of Adams’ that you wouldn’t be able to take now. The moon over Hernandez, for instance, you couldn’t recreate these days. There’s been some development—there’s a Wal-Mart and a road now. But the High Sierra area, the Ansel Adams Wilderness, that’s stayed the same because it’s protected. I even went to some of the spots and stood my tripod in a hole exactly where Ansel Adams stood his.

I think the real change is in how we see wilderness... back in Adams’ time it was a place to get away and enjoy yourself. It still provides that for us, but now we’re seeing wilderness as set apart, a refuge when all of the other areas have been developed. These are some of the only areas where we can still see wild nature. It makes you reflect—everything was once wild and now there are only these little fragments left. That’s the real change, the development that’s taken place in the years between Adams’ photos and mine, and the change in perspective that’s occurred alongside it. We all still need the tonic of wilderness, so to speak. The peace that people went into the wilderness looking for in the twenties and thirties is something we need even more so today.

S: I was fascinated by the idea of extracts, which you mention in the book. Can you tell me more about that?

PE: That was Adams’ huge leap forward in landscape photography. Back in his day the equipment was so heavy and cumbersome that most photographers just did survey photography. They weren’t thinking of it as personal expression or art, they were simply documenting. Adams, though, captured just a section of a landscape. He used to say that nature is made up of shapes, and the artist’s job is to make form out of them. The way you do that is by including your own emotional response as a photographer. He revolutionized nature photography by bringing in the feeling of the extract. So that’s what I tried to do. For other assignments you put together a shot list and you know what you need to get to supplement the story, but for this project I just had a list of places I wanted to go and trails to follow. I went, I set up camp, and took pictures of whatever caught my eye—I tried to respond to it personally.

S: Talk to me about how Adams influenced you as a photographer.

PE: Ansel Adams was a big influence when I was first starting out—he had these basic manuals about how to be photographer that I read when I was in high school and taking my first photos. A lot of Adams’ artistic theories first developed when he was out climbing, taking in all these natural phenomena, photographing in the high mountains, and I had a similar experience. My father was a science teacher and he liked the outdoors, so he took me around the Death Valley and Yosemite. I started to develop my love of the outdoors from him, and that's been a great influence on my trajectory as a photographer.

S: Most of the nature photos that we see these days are in color. What does black and white have to offer the medium?

PE: This area photographs really well in black and white. When Adams first started that’s all that was available, but he always said that it was a departure from reality. He liked the fact that you had a lot of control over it—at the time, you couldn't manipulate color film in the dark room the way you could with black and white. When the publishers and I thought about whether we wanted to do it in black in white, we thought it might be harder because it would feel more like we were copying Adams. But I also thought it would be more of challenge to do something novel and do it in black and white. With digital you can open the image in color or in black and white, and I discovered that I really preferred most of the black and white images. The granite of the area is gray already and the sculptural form of it is more apparent if you take away the color. Black and white allows the shadows to play with the rays of light, and light as form shows up better. That’s the role of the artist in any kind of medium, I think: an attempt to give the viewer a sense of the place and of one person’s feelings about it always results in the best art, and that really comes through in black and white.

S: What was it like for you, spending extended periods of time in the wilderness?

PE: After the first few days you forget about the office. At these higher elevations, above the tree line, it’s sort of like a lunar landscape, a different world. That’s when you can really start to feel a connection to the earth and the landscape, after those first few days, when you get away from all the emails and cell phones. It helps your photography too. You start to focus on trying to capture your feelings about the place, you feel more in tune and more responsive to the landscape.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club