>> Download our brochure on vegetation management for fire safety in the East Bay hills

Given the very serious drought conditions facing California, combined with longer and more serious wildfire seasons due to climate disruption, it’s more important than ever to prioritize fire prevention in our vegetation management strategies for the East Bay hills.

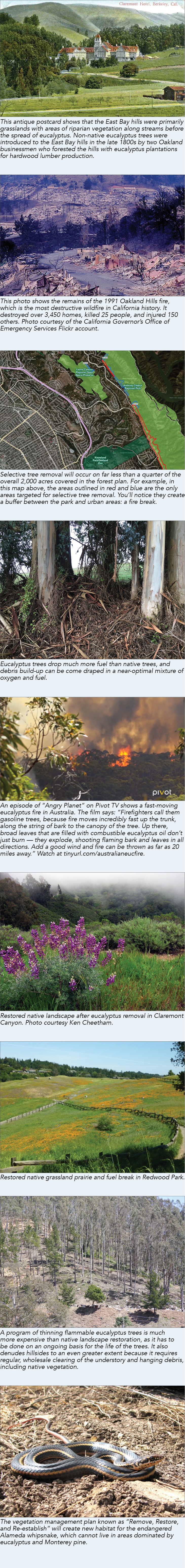

Ever since the Great Fire of 1991 ravaged the East Bay hills at a cost of 25 lives and 3.9 billion in present-day dollars, the Sierra Club has worked with fire experts, public officials, and environmental groups like the Golden Gate Audubon Society, the California Native Plant Society, and the Claremont Canyon Conservancy to develop an ecologically and fiscally sustainable model for fire management that not only reduces the risk of fires, but also promotes diverse and healthy ecosystems.

The preferred strategy for vegetation management in the East Bay hills entails removing the most highly flammable, ember-generating trees like eucalyptus in phases — only in select areas considered most at risk for fire along the urban-wild interface. Once the flammable non-native trees are removed, less flammable native species can reclaim those areas and provide for a rebound of biodiversity. This model of fire prevention can summarized as the the “Three R’s”:

- REMOVE the most flammable non-native trees in select areas most at risk for fire;

- RESTORE those areas with more naturally fire-resistant native trees and plants; and

- RE-ESTABLISH greater biodiversity of flora and fauna, including endangered species like the Alameda whipsnake.

Clearing up misconceptions

There is a lot of misinformation floating around about this preferred model for the care and management of vegetation in the East Bay hills. Here are the facts about a few of these misunderstandings:

The Sierra Club’s approach does NOT call for clearcutting. Under “Remove, Restore, Re-establish” thousands of acres of eucalyptus and other non-natives will remain in the East Bay hills. Our proposal only covers areas near homes and businesses where a fire would be most costly to lives and property, and only those areas that are best suited for native forest restoration (see map). In fact, removing monoculture eucalyptus groves and providing for the return of native ecosystems will create a much richer landscape than the alternative — thinning — which requires regularly scraping away the forest floor to remove flammable debris.

In those areas targeted for selective removal, only the most-fire-prone invasive trees will be culled in order to create fuel breaks and prevent the spread of wildfire. Once the eucalypts — which suck the water, prevent sunlight from reaching the understory, drop literally tons of detritus, and produce allelopathic oils that inhibit the establishment of other species — are removed, the existing understory of oaks, bays, and willows will thrive. Existing native plants in the understory will be preserved and replaced naturally.[i] Grass and shrub land will be restored, depending on the exact location.

Native landscapes provide habitat for much more diverse ecosystems. Birds and mammals much prefer native woodlands to the dense, inhospitable eucalyptus.[ii] If implemented, the plan supported by the Sierra Club will create additional habitat for the endangered Alameda whipsnake, which cannot live in areas dominated by eucalyptus and Monterey pine.[iii]

After the work is done, thousands of acres of eucalyptus, Monterey pines, and other non-native trees still will remain in the East Bay hills.

Our preferred approach does NOT focus on eucalyptus merely because they are non-natives. Rather, it is because they pose a far higher fire risk than native landscapes. Eucalyptus trees are called “gasoline trees” in Australia for their tendency to explode in fireballs at very high temperatures.[iv] They drop far more flammable litter per acre than native trees and their embers stay lit longer and fly farther than embers from other vegetation.[v] Fire officials have concluded that the 1991 Oakland Hills fire was spread by the large eucalyptus, pine, and acacia.[vi] Embers from these tree species flew onto nearby homes and blew rapidly across wide areas. Native trees, shrubs, and grasses do not catch or spread fire the way eucalyptus trees do. Wood chips from selectively removed non-natives decompose rapidly and have a very low air-to-fuel ratio, limiting the speed at which a fire can travel.[vii]

If used, herbicide would be applied in minute quantities under strict environmental controls. The herbicide Garlon, or triclopyr, has been proposed as a solution to the rapid growth of eucalyptus stump sprouts (the “hydra effect”). Without intervention, eucalyptus stumps re-sprout in much denser quantities with as many as six or eight trees growing from what was once a single stump. They grow up to six feet a year.[viii] We encourage the land-managing agencies to explore all viable, natural solutions to resprouting.

In those cases that herbicides are the most effective remedy available, we insist on a full environmental review and the strictest controls to prevent possible negative effects. The amount of herbicide would be limited to one to two ounces per tree and would be applied directly to each stump.[ix] Strict controls would be in place so that herbicides would not spread to other trees, wildlife or people.[x] The personnel applying them will be specially trained and supervised. Roundup, or glyphosate, would be used sparingly to control broom in restored landscapes. Comparing this use of herbicide to the regular broadcast spraying of farmland elsewhere is a misrepresentation of fact.[xi]

[i] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Biological Opinion for the Proposed Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Hazardous Fire Risk Reduction Project in the East Bay Hills of Alameda and Contra Costa Counties, California.” Page 5.

[ii] U.S. Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station. “Abundance, distribution, and population trends of oak woodland birds.”

[iii] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Biological Opinion for the Proposed Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Hazardous Fire Risk Reduction Project in the East Bay Hills of Alameda and Contra Costa Counties, California.” Page 78.

[iv] Carol Rice. “The Science Behind Eucalyptus Fire Hazards.”

[v] US Forest Service Fire Effects Information System database. "Index of Species: Eucalyptus globulus."

[vi] D. Boyd. 2000. Eucalyptus globulus. pp. 183-186 in Bossard, C. C., J.M. Randall, and M. C. Hoshovsky. "Invasive Plants of California's Wildlands." University of California Press. Berkeley, CA.

[vii] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Biological Opinion for the Proposed Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Hazardous Fire Risk Reduction Project in the East Bay Hills of Alameda and Contra Costa Counties, California.” Page 8.

[viii] Roger G. Skolmen and F. Thomas Ledig. “Bluegum Eucalyptus.” Silvics Manual, 2002.

[ix] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Biological Opinion for the Proposed Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Hazardous Fire Risk Reduction Project in the East Bay Hills of Alameda and Contra Costa Counties, California.” Page 49.

[x] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Biological Opinion for the Proposed Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Hazardous Fire Risk Reduction Project in the East Bay Hills of Alameda and Contra Costa Counties, California.” Page 48.

[xi] California Invasive Plant Council and Pesticide Research Institute. “Best Management Practices (BMPs) for Wildland Stewardship: Protecting Wildlife When Using Herbicides for Invasive Plant Management.” Page 12,